Between Conversion and Repentance: Christian Wiman on the Uses of Fiction

“Once I wanted poetry to save me. From what? For what is the better question.”

I.

The mansion in Hollywood had a vast ballroom that was empty except for a thick rope that hung from the thirty-foot-high ceiling to the floor. The owner was a director, famous in that famished and downward way that the ascendant wolves can sniff out like weak meat, and the rope was, it turned out, his exercise. Every day he monkeyed up and down fifty times, or so he told me, and his barrel arms, baroque sexuality, and tenuous and strenuously tanned sanity made it an easy claim to believe. He was sleeping with my girlfriend’s identical twin sister, and one night over sushi she and Sam spoke in their special language about the size of his penis. By that time I could pick up a word here and there. Sam lived in a ghetto compound owned by a painter known around the world for work influenced by “the deadpan irreverence of the Pop Art movement.” It was rented exclusively to other artists, though the definition of that word was elastic enough to include a set designer and a bottom-drawer rock star. My favorite of the bunch was MacLean, a scotch-soaked Scottish painter whose outlandish life was inked all over his hard hairless body like cave paintings and cuneiform. Sitting out in the courtyard one evening after a young woman had delivered a litany of romantic sufferings, he said tenderly, “Ah, fuck it, lass, it’s all just subject matter anyway.” That was the same night that little bastard Harry bit me. Harry was Sam’s disconcertingly percipient poodle, and there is a picture of me holding him that very night, something flagrant, almost obscene, in my youth and health. That was also the night we decided to destroy the baby in Sam’s uterus, and the next morning I sat in the waiting room of a clinic in Santa Monica trying to pretend the decision had been difficult. One of the illusions of age is the feeling one has looking back at the past that there was a time before one’s real self had emerged, or the wrong cells had begun to divide, or the moral sense had set like a foundation. “Necrotic,” the nurse at the clinic said of the cells that had been removed, which felt to me like such a relief—such a blessing, really—that I couldn’t understand the implacable sadness Sam assumed in the days after, the dark murk of absolute and involute silence she peered only partway out of like a lovely crocodile. Of course that is not altogether true. Of course we lasted only another month or so before I went back to San Francisco and the novel that would make me famous, she picked up with a director (not the rope-climber), I slouched into bed with a woman who danced in a cage at a club, and we drifted out of each other’s orbits as lonely and inchoate souls tend to do. (Which is to say, not quite, as elusive and entangled as fog.) Years later I encountered Sam after a lecture I had given in a church in Washington, D.C. We both had children and exchanged pictures. The lecture was on the line between belief and unbelief, how there is no line, really, how to be devout means to be at risk, to live with the understanding that all one’s assumptions might be overturned in the blink of an eye, that even the nothingness that swallows up every last atom of faith might be, if we have eyes and ears to perceive it, a piece of grace. The Greek word for repentance is metanoia, which means, rather than mere regret or remorse, something closer to a transformation of one’s entire being. A certain static sorrow has entered the English. It will never come out.

One of the illusions of age is the feeling one has looking back at the past that there was a time before one’s real self had emerged.

II.

A butterfly is stuck to the mesh around the store-bought firewood outside the back door this morning. I watch my daughter watching it. Large black wings crimsoned with matching markings, pulsing like some exquisite viscera. It’s appalling, sometimes, to see life pouring into a child like a torrent too big for its channel. Yesterday, coming out of the parents’ meeting at the therapist’s office, I said there was something about the nature of that therapeutic language that was inimical to my imagination, and D. said, “You mean inimical to your repressions?” A sudden squall, snow battering our faces like moths, traffic crawling down Whitney, another month, another meeting. “Tell me a time when you were bad, Daddy.” Age increases experience even as it narrows one’s possible reactions to it. Iron tracks have been laid down and long traveled. To deviate would require a crash. My own childhood was full of sourceless rages, solitudes so abysmal they retain exact position and proportion in the mind, like the objects left by astronauts on the moon that, because there is no atmosphere, exist exactly as they were. Not one particle has been lost or changed. But rage, too, is a reflex, I want to say, like grief, like God. There are times in one’s life when form is a lapse of courage. “Love is the extremely difficult realization that something other than one’s self is real.” Sun-haired, sky-eyed, she turns her ten years toward the shadow that I am.

III.

His shadow lay over the rocks as he bent, ending. Why not endless till the farthest star? Darkly they are there behind this light, darkness shining in brightness, delta of Cassiopeia, worlds. Me sits there with his augur’s rod of ash, in borrowed sandals, by day beside a livid sea, unbeheld, in violet night walking beneath a reign of uncouth stars. I throw this ended shadow from me, manshape ineluctable, call it back. Endless, would it be mine, form of my form? Who watches me here? Who ever anywhere will read these written words? Signs on a white field. Somewhere to someone in your flutiest voice. The good bishop of Cloyne took the veil of the temple out of his shovel hat: veil of space with coloured emblems hatched on its field. Hold hard. Coloured on a flat: yes, that’s right. Flat I see, then think distance, near, far, flat I see, east, back. Ah, see now! Falls back suddenly, frozen in stereoscope. Click does the trick. You find my words dark. Darkness is in our souls, do you not think? Flutier. Our souls, shamewounded by our sins, cling to us yet more, a woman to her lover clinging, the more the more.

–James Joyce, Ulysses

IV.

“Sin”? It’s not a word with much resonance for me. Which is precisely the problem, my more pious friends might say. Pious, too, I toss off scoffingly. Once I wanted poetry to save me. From what? For what is the better question. To whom am I speaking? Tell me a time. They strap you down. They tie your feet together. They lock your head between cushioned clamps, for if you move then all the waiting, the fasting, the yearning to have an answer—it comes to nothing. Still I spasm. Every time. Can’t keep from sleeping. MRIs, too, clang and bang and Katy bar the crazy, twitching talking up out of dreams as from sludgy water. Me to whom sleep so otherwise is, so warily comes. Kitty-kitty. “I just want one present for my birthday and well it’s kind of a big one so don’t say anything at all when I say ‘It’s a kitten!’ Skipping liquidly off as if she were one. Tell me a time. In the noncanonical Acts of Peter, our eponymous apostle is crucified head down—symbolizing, some say, the inversion of values a life in Christ requires. Nailed, impaled, good Peter has the presence of mind for one last lecture. Scoffingly. I, too, am porcupined, elusive, evasive, rife with hate. “Darkness is in our souls, do you not think, Daddy?” The central nail between the beams of Peter’s cross symbolized both repentance and conversion, the hydraulic drag of the past and the spirit’s fling forward, the provocation of sorrow and the transformation to light. Two movements, fused. Metanoia. Though in fact as I recall the writer of the Acts of Peter sought to preserve a distinction between conversion (epistrophe) and repentance (metanoia). There are times in one’s life when form is. “I don’t really believe in God, Daddy.” Love is the supremely difficult. Abysmal the stillness, the waiting, the end that isn’t. “Only the man who has had to face despair is really convinced that he needs mercy.” The butterfly wasn’t stuck at all she says bursting in to where I am. It was clinging.

__________________________________

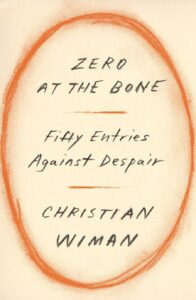

Excerpted from Zero at the Bone: Fifty Entries Against Despair by Christian Wiman. Published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux. Copyright © 2022 by Christian Wiman. All rights reserved.

Christian Wiman

Christian Wiman is the author, editor, or translator of more than a dozen books of poetry and prose, including two memoirs, My Bright Abyss: Meditation of a Modern Believer and He Held Radical Light: The Art of Faith, the Faith of Art; Every Riven Thing, winner of the Ambassador Book Award; Once in the West, a National Book Critics Circle Award finalist; and Survival Is a Style—all published by FSG. He teaches religion and literature at the Yale Institute of Sacred Music and at Yale Divinity School.