Benjamín Labatut Will Not Be Profiled

But Adam Dalva Tries Anyway

I sensed that Benjamín Labatut would be a challenge to profile because his work is heady and elusive. His English-language debut, When We Cease to Understand the World, was part-essay, part-fiction, a fractal sequence that dove into the imagined minds of scientists and mathematicians like Werner Heisenberg and Erwin Schrödinger. Labatut’s wonderful new book, The MANIAC, is a triptych that centers on John von Neumann, a Hungarian polymath who conducted foundational work on computer science, game theory, and nuclear weaponry. The MANIAC opens in the vein of WWCtUtW, with a profile of Paul Ehrenfest, a mathematician who murdered his son, and it ends brilliantly with Lee Sedol’s game of Go against the computer Alpha Zero. Once again, some of the book’s plot is real, and some is invented.

I did at least assume that this piece would be a welcome development for Labatut. I’d fly to Chile, chat with him, and do some whimsical activity (a game of Go?)—all in search of what the critic Parul Seghal calls a “moment of self-revelation” that would superficially capture the man behind the prose. Easy enough.

But Benjamín Labatut did not want me to come to Santiago. He didn’t want to do a Zoom. He did not want to be described at all. Now, in nearly every situation, not wanting to speak with me is a reasonable desire. And profiles usually ignore the lonely misery of creation in favor of a pre-packaged likability that might, by little-understood-alchemy, transmute into book sales. Though I admire Labatut’s stance, I wasn’t sure how to proceed. I couldn’t resort to fiction, and I didn’t want to write a hit piece, the lazy writer’s friend, because I admire his work. “I’m a journalist and a writer, so I consider any piece a hit piece,” Labatut told me when I shared my dilemma. “The reason I get so huffy about interviews is that I don’t have definite views.”

“The only thing I find striking about myself (and I’m not at all proud of this, but I have to admit to it openly) is how many books I simply detest,” he wrote in a separate email—our correspondence ended up being several times the word count of this piece. When we discussed books that he did like, he pointed me away from contemporary fiction and toward inter-genre writers like Pascal Quignard, Roberto Calasso, W.G. Sebald, and Eliot Weinberger, all of whom I read with pleasure, hoping to establish a common ground.

If I was going to keep this profile’s focus on Labatut’s work, I also needed to read his oeuvre—but even that was a problem. His first two books are nearly impossible to find. They’re in a few libraries but can’t be checked out, which is a further obstacle, because they were written in Spanish, a language I do not speak. La Antártica empieza aquí, an early story collection that won a student contest, is out of print, and the mysterious Después de la luz, Labatut told me, is “not something I want many people to see.” He also wouldn’t provide the unreleased English version of his more recent book, The Stone of Madness.

His first two books are nearly impossible to find. They’re in a few libraries but can’t be checked out, which is a further obstacle, because they were written in Spanish, a language I do not speak.

I began to feel panicked—I wanted to finish this essay, because I was pot-committed, and because I think Labatut’s work is worth deep thought. But I had no writer; I had no writings. Then, someone on deep background guided me toward illegal copies of the early work (from this: a computer virus!) and I commissioned Spanish translator and critic Samuel Rutter to write book reports for me.

I meanwhile asked Labatut if he would clarify his back-jacket biography, which he had elsewhere described as inaccurate.

“I was born in Rotterdam in 1980,” he told me, “We moved to Chile when I was two, and lived in Santiago till I was eight, when my parents moved back to The Hague. I stayed there till I was thirteen, then we moved back to Santiago…I also spent quite a long time in Buenos Aires because of a girlfriend (the one who saved me from the Lord).”

That kicker may have caught your attention. Labatut “suffered a brief period of intense, all-consuming faith when I was young…I had part of that same passion that tortured Ehrenfest, one that makes you not want to know, but need to know.”

The MANIAC tracks this linkage between madness, religion, and genius. The centerpiece is a virtuosic 238-page faux oral history of von Neumann that’s reminiscent of the central section of Roberto Bolaño’s Savage Detectives. Fourteen narrators, all real, ranging from Richard Feynman to von Neumann’s daughter, Marina, speak in round. Their language is invented, but most of the plot is drawn from life, with other geniuses of the century continually left dumbfounded by the protagonist’s uncanny intelligence.

I asked Labatut why he didn’t provide von Neumann’s perspective in The MANIAC. He told me that “a single narrator has too much authority…Monsters and gods should not be given a voice.” What seems most monstrous about von Neumann in the context of Labatut’s project is his sanity. A cancer that may have stemmed from Los Alamos kills him young, but “the Martian” remains perfectly himself throughout the novel, while most of the other geniuses—Georg Cantor; Kurt Gödel; Nils Aall Barricell—descend into madness.

The MANIAC was written in English. “I’ve been completely bilingual since around age seven,” Labatut told me when I asked why he had not continued to work with the capable translator Adrian Nathaniel West. “Because I don’t want to get in too much trouble, I will simply quote Borges, who admitted that he found English “a far finer language than Spanish”.

My own Spanish translator had meanwhile finished reading and told me that La Antártica empieza aquí is a good collection that wears its influences on its sleeve, that The Stone of Madness is an essay about, in part, a woman who claims that Labatut is plagiarizing her work, and that Después de la luz begins with Labatut suffering from extreme melancholy. “From one day to the next, the world stopped feeling real to him, and when medication and therapy were of no use, he tried to read his way through the ennui,” said Rutter.

“In Chile,” Labatut told me of Después de la luz, “critics compared me to the people I hate the most. Spiritual charlatans or just people who are high on their own supply, enamored of their own bullshit.”

There’s something incontrovertible about Labatut’s recent subjects—Heisenberg, John von Neumann, even a champion go-player, all share a sort of left-brain genius that’s both easy to understand and impossible for someone like me to fathom. Could Labatut’s reluctance to appear in this piece mirror his transition away from the subjective creative self toward the objective world of hard science? Is depersonalizing a profile a way of controlling it?

Could Labatut’s reluctance to appear in this piece mirror his transition away from the subjective creative self toward the objective world of hard science? Is depersonalizing a profile a way of controlling it?

“There’s no text that I’ve written in the last 10 years that I haven’t learned something from, because it’s always focused on the world, on other people’s ideas,” Labatut told me. “And self-expression doesn’t come into it at all. I try to avoid it as much as I can…Wasn’t it great back when a writer said ‘I’ and you knew they were lying?”

In Ruth Franklin’s New Yorker review of WWCtUtW, she suggested that there’s “something questionable, even nightmarish,” about Labatut’s project. “Is it responsible for a fiction writer, or a writer of history,” she asked, “to pay so little attention to the line between the two?”

Contra-Franklin, I believe that artmaking of this caliber is a responsible human act, but it’s true that Labatut is gnomic about his process, emailing things like “the trick is to be able to spot the tiger hidden among the trees.” In search of clarity, I reached out to John von Neumann’s daughter, Marina von Neumann Whitman.

Dr Whitman is 88 years old, refreshingly forthright, and totally fascinating. She grew up next door to J. Edgar Hoover, quit Nixon’s council of economic advisors over Watergate, and, in a great scene in her autobiography, The Martian’s Daughter, is cutting to Arthur Koestler at a dinner party.

Dr. Whitman read The MANIAC and said that the section about her father was neither “violence” nor “violation.” I had the sense that she’d enjoyed it—something I had been nervous about before our call, since the novel takes several invented leaps in the last part of the von Neumann section. “I do have to sort out what is based on reality and what is not,” she said. She also found it uncanny that Labatut knew things about her life that weren’t in The Martian’s Daughter, like a piece of graph paper that she’d carried in her pocket as a girl.

“Those specific details are usually absolutely real,” Labatut told me. “So I must have gotten that from somewhere. You still have to do what I did, which is see every single talk she gave. I walked around 24 hours a day for a couple of years listening to these people. And then, and this is why she doesn’t recognize it, I took 200 pages out of the book.”

Dr. Whitman did complain that Labatut, in her section of the invented oral history, used a word she would never utter: “hubby.” “Oh, come on. Sure,” Labatut laughed. We were on a Zoom, which he had eventually agreed to.

I had promised not to take pictures of our call, so I furtively wrote description as we chatted—wet hair, beautiful modern apartment, a mysterious figure on his balcony. Unfortunately, I was confounded by his garment, which at various points I thought could be a track suit, a rain jacket, or a winged cloak. Finally, I settled on a kimono-like robe.

Labatut was garrulous and charismatic, not at all the reluctant figure I’d feared. He started writing late, unable to shake his creative ambition. “It doesn’t matter how successful you become in South America,” he told me. “You’re never going to live off literature. You go into it knowing that it’s a failed enterprise.”

Labatut was garrulous and charismatic, not at all the reluctant figure I’d feared.

After he began to write, he was sent by his friends, “and I swear this is true,” he said, to the “old man,” a dying poet, Samir Nazal. “I walked into his apartment, and he had a long unkept beard and was covered in cigarette burns.” Nazal taught Labatut to write—”when he died, he’d never published a word. He had these containers with everything he had written. They were in Tupperware because it rained in his apartment. And I see him in dreams. I see him in hallucinations. Without the old man, I don’t think I would’ve ever written.”

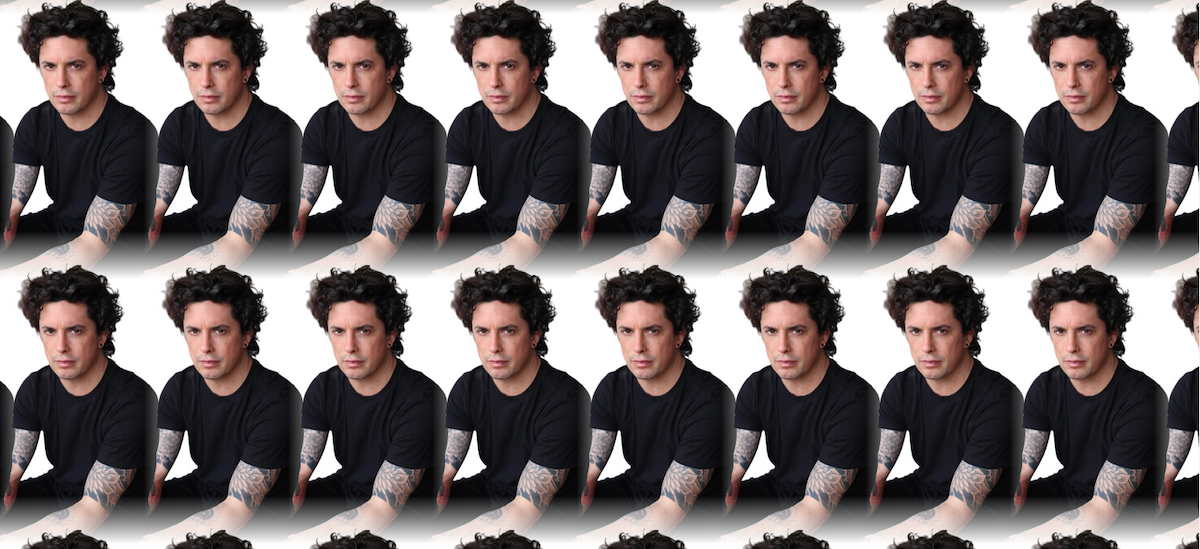

Photo by Benjamin Labatut.

Photo by Benjamin Labatut.

Labatut was a “nothing journalist” for FAO for almost two decades, refusing promotions so he could focus on his writing. “I had lunch by myself every day for 17 years. I wouldn’t accept any invitations.” Eventually, he realized that, for him, “literature requires a sort of certain controlled psychosis,” and his ongoing project bloomed.

“What I’m trying to do, and I’m trying to hide it, but not very well, because I’m sure you realize it,” he said, “is say that there is a certain genie in the equation…I cannot help but see that when we look down at our phones, it’s prayer.”

This intersection of technology and spirituality is embodied by von Neumann, Labatut’s “tiny mad God”, who becomes, in a stunning invented sequence, a ghost in the machine. “I get as close as I can to reality, and then step back,” Labatut said of that moment. “What are the stranger meanings that are coming through? What things didn’t happen but should have happened? I’m doing an exercise in apocryphalism.”

As we wrapped up, he reminded me again to stay focused on his work. “The less they know the better,” he said. “And I’m such an interesting person,” he added, a flash of—could it have been glee?—in his eyes. “You have no idea.”

Adam Dalva

Adam Dalva’s writing has appeared in The New Yorker, The Paris Review, and The Atlantic. He is the Senior Fiction Editor of Guernica Magazine and serves on the board of the National Book Critics Circle.