Behind the Scenes of Roger Corman’s Campy, Culty The Little Shop of Horrors

The Inspiration for the Off-Broadway Musical Was One of the Cheapest Hollywood Films Ever Made

Some movies are made for art, some for profit, and some in order to win a bet. The Little Shop of Horrors falls in the third category. Perhaps it was not so much a bet as a challenge: could a feature-length film be shot in exactly two days? Roger Corman, an independent producer and director, said Yes. He rose to prominence in the 1950s, when the Hollywood studio system was crumbling. The federal government forced Paramount and other studios to sell off their movie theaters; families migrated to suburbia and stayed home to watch television; and the moguls who once led the system—Louis B. Mayer, Harry Cohn—were dying. The cinema audience was also getting younger, ready to rebel without a cause, more attuned to the macabre. Attack of the Crab Monsters. A Bucket of Blood.

Corman thrived in the changing climate. Born in Detroit, Michigan, in 1926, he was raised in the Great Depression, forever haunting his relationship with money. He studied industrial engineering at Stanford University and then English literature at Oxford before he drifted into the movie business. Living in Los Angeles and working outside the system, he produced films for pennies and always turned a profit. Vincent Price called him “dead serious, humorless.” Corman, with sufficient preparation, could shoot a film in five or six days. “I had never thought of myself as doing Great Art,” he said. “I felt I was working as a craftsman.”

A longtime Corman assistant, Beverly Gray, noticed “the engineer’s zest for problem-solving.” Actor Mel Welles, who appeared in many Corman films, observed that the director solved problems “with the greatest amount of efficiency.” Prolific and reliable, he became a key supplier for American International Pictures (AIP), a company formed in the 1950s by James H. Nicholson and Samuel Z. Arkoff. According to one critic, AIP “specialized in fun, hip, sexy, and contemporary alternatives to Hollywood’s stuffy spectacles and mundane melodramas.” In the summer of 1957, for example, AIP offered Invasion of the Saucer Men, I Was a Teenage Werewolf, and Reform School Girl. Growing up in New Jersey at the time, Joe Dante noticed that “they were movies your parents wouldn’t want you to see.”

AIP offered Corman $50,000 for each film he produced, plus a $15,000 advance on foreign sales. So Corman completed each film for under $65,000; every third or fourth film would be extremely cheap, thus increasing his profits. Nevertheless, Corman bristled at the well-known term for low-budget Hollywood fare: “I never made a ‘B’ movie in my life.” He insisted that the B movie (the second half of a double feature) was a relic from the 1930s and 1940s, when the major studios controlled production, distribution, and exhibition. Yet in the era when color photography became affordable for the majors, AIP found a winning formula by combining two similar black-and-white pictures into a double feature: “two films for the price of one.”

The legend that Roger Corman produced The Little Shop of Horrors in two days has often been told. However, Corman biographer Mark Thomas McGee argued that “the legend is a lie.” Here is what happened. In 1959, Corman formed his own company, the Filmgroup, which generated movies on the AIP model: fast and cheap. When offered free access to a movie set that depicted an office, Corman brainstormed ideas with a frequent collaborator, the screenwriter Charles Byron Griffith, known as Chuck. They considered a story about cannibalism but feared that it would never get past the censors.

Late one night, when such ideas emerge, Griffith suggested a “man-eating plant.” The resulting screenplay resembles a Corman-Griffith film made earlier that year, A Bucket of Blood. Both projects center on the same trio: a hapless loser, his love interest, and his boss. To economize, each story is built around a single workplace location (a beatnik café, a florist shop), and in each case, the loser-hero becomes an accidental murderer, thus winning attention and the love that he craves. Griffith entitled his new script “The Passionate People Eater”—a variation on “The Purple People Eater,” a 1958 novelty song by Sheb Wooley. In the song, a creature from another world descends to the earth and proclaims, “I want to get a job in a rock ’n’ roll band.” So the song blends a monster movie and rock music: a potent combination.

Perhaps it was not so much a bet as a challenge: could a feature-length film be shot in exactly two days?

In December 1959, “The Passionate People Eater” went into production. Corman intended to beat his own record for speed and shoot in just two days. On Tuesday, December 22, Corman began filming at the former Charlie Chaplin Studios, on North La Brea Avenue, near Sunset Boulevard. On Wednesday, production wrapped. How did he do it? He shot with two cameras simultaneously to get more coverage in less time. The actors were engaged for one week; they rehearsed for three days and shot for two.

All the scenes in the florist shop play out as if on stage; the editor cuts between angles, left and right. The film’s interiors are high key and low contrast; indeed, these scenes look more like a multicamera sitcom than a monster movie—appropriate for Corman’s blend of comedy and horror. The story also required about 12 minutes of exterior photography, which took place over four evenings, produced by a non-union crew. Since Corman was in the union, directing duties here were handled by Chuck Griffith. Hence the shoot was a few days longer than the legendary two days.

“My film budgets have always been notoriously lean,” Corman admitted.

Beverly Gray recalled that he would “hire young unknowns who would work for almost nothing in exchange for the chance to learn their craft.” In A Bucket of Blood, the hero exclaims, “Gee, 50 dollars for something I made!” His coworker replies, “Now you’re a professional.” For the film that became The Little Shop of Horrors, the lead actor, Jonathan Haze, was paid $400 for a week of work; a prop company called Dice Incorporated charged $750 to construct four mechanical plants of increasing size and menace. Multitalented Chuck Griffith earned $1,800 for writing the screenplay, acting in the film, and directing the exterior scenes. A young Jack Nicholson also appeared in the film, as a masochistic dental patient. When offering the role, Corman handed Nicholson only those script pages in which the actor would appear. “That’s what low budget was like,” Nicholson remembered. The total cost: less than $30,000.

Corman bristled at the well-known term for low-budget Hollywood fare: “I never made a ‘B’ movie in my life.”

Retitled The Little Shop of Horrors, the film opened at the Pix Theatre, in Hollywood. Nicholson attended, and there was a strong reaction, at least to his scene: “They laughed so hard I could barely hear the dialogue.” Here’s what the audience saw: Business is bad in a low-rent florist shop on Skid Row, run by Gravis Mushnik. He has two assistants: Audrey and Seymour. Seymour, a budding botanist, discovers a new kind of carnivorous plant, which eventually eats four people. The remarkable plant grows and attracts business to the now-booming shop; as a result, Seymour wins popular acclaim and the love of Audrey. The police, however, investigate the murders and find their way to the florist shop, but Seymour eludes them. Finally, he tries to kill the plant and dies in the process.

Cheap exploitation pictures such as this one generally did not command many reviews. But the industry journal Variety offered a positive notice, in 1961, months after the film first appeared. The reviewer found The Little Shop to be “one big ‘sick’ joke” but also “harmless and good-natured.” Further, “Horticulturalists and vegetarians will love it.” On the other hand, exploitation films were lavished with colorful artwork created by publicity departments eager to sell the studio’s product.

A typical poster might suggest epic scope, when in fact the advertised film is nothing more than a few people running around the San Fernando Valley, occasionally menaced by a rubber monster. The poster for The Little Shop of Horrors is elegant and strange—clearly the artist never saw the picture. The period is now the early 20th century. Perhaps the artist remembered the old-world charm of The Shop around the Corner, the 1940 M-G-M film based on a Hungarian play. A tagline on The Little Shop poster is adapted from a song in Gilbert and Sullivan’s The Mikado, appended by musical notation: “the flowers that kill in the Spring / TRA-LA.” So The Little Shop of Horrors, a horror-comedy, appears to be a musical.

A lobby card for the original 1960 film, signed by the producer and director, Roger Corman. The vocal phrase and notes at the top suggest a possible musical.

A lobby card for the original 1960 film, signed by the producer and director, Roger Corman. The vocal phrase and notes at the top suggest a possible musical.

Nevertheless, the Filmgroup encountered difficulty distributing the new film. It appeared as the lower half of a double bill in September 1960, paired with more elaborate Corman productions, House of Usher or Last Woman on Earth. Some exhibitors refused to book The Little Shop because they perceived that it was anti-Semitic. The major characters seem to be Jewish, and they are morally suspect. The nebbishy hero, Seymour Krelboin (or Krelboined), kills people and then feeds them to his hungry plant; Seymour’s employer, Mr. Mushnik, fails to report the crimes because business is now profitable. Nevertheless, in 1961, the film was invited to appear (out of competition) at the Cannes Film Festival. Back at home, AIP rescued the languishing Little Shop when the company needed a second feature to accompany Black Sunday, an Italian shocker that AIP acquired for US distribution. By May, Corman devised a new release pattern, with a focus on art-house cinemas and “special college town campaigns.” Like many low-budget films, The Little Shop of Horrors played in smaller theaters and drive-ins before it disappeared.

But in the mid-1960s, Corman sold a number of Filmgroup pictures to television, through Allied Artists, and the movie about Seymour and his carnivorous plant found a new audience. Mel Welles, who played Mushnik, discovered that “[i]t became a kind of cult film.” One critic explained how the iconic plant’s dialogue entered the popular consciousness: “Every time it’s on television, school kids go around yelling, ‘Feed me! I’m hungry!’ the next day.”

Corman’s movie appealed to slightly older students as well; Mark Thomas McGee recalled that “college kids started watching it. They’d all toke up and think it was even funnier than it was.” Character actor Dick Miller, who appeared in The Little Shop and other Corman films, said that the director “didn’t think these things would ever go anyplace.” Yet, according to Welles, The Little Shop of Horrors “caught the imagination of the young people, the hipsters of the time.”

One of these young people was Howard Ashman. Around the age of 14, he watched the film on a black-and-white TV and was smitten. Two decades later, he remembered the story about the man-eating plant. Ashman reimagined Corman’s nasty little thriller as an Off-Broadway show, with music by Alan Menken. Audiences have been singing “Little Shop of Horrors” ever since.

____________________________

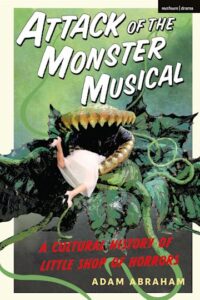

Adapted from ATTACK OF THE MONSTER MUSICAL: A Cultural History of Little Shop of Horrors by Adam Abraham. Copyright © 2022 by the author and reprinted with permission of Bloomsbury Publishing.

Adam Abraham

Adam Abraham is the author of When Magoo Flew: The Rise and Fall of Animation Studio UPA and Plagiarizing the Victorian Novel: Imitation, Parody, Aftertext. He has also written for film, television, and theatre. Now a Visiting Assistant Professor at Cornell College, he previously taught at Auburn University, Virginia Commonwealth University, New York University, and Oxford.