Before They Were Cliches: On the Origins of 8 Worn Out Idioms

Erin McCarthy and the Team at Mental Floss Examine Some Famous Phrases

Worn-out phrases can make a reader roll their eyes, or worse—give up on a book altogether. Clichés are viewed as a sign of lazy writing, but they didn’t get to be that way overnight; many modern clichés read as fresh and evocative when they first appeared in print, and were memorable enough that people continue to copy them to this day (against their English teachers’ wishes). From Shakespeare to Dickens, here are the origins of common literary clichés.

*

Add Insult to Injury

The concept of adding insult to injury is at the heart of the fable “The Bald Man and the Fly.” In this story—which is alternately credited to the Greek fabulist Aesop or the Roman fabulist Phaedrus, though Phaedrus likely invented the relevant phrasing—a fly bites a man’s head. He tries swatting the insect away and ends up smacking himself in the process. The insect responds by saying, “You wanted to avenge the prick of a tiny little insect with death. What will you do to yourself, who have added insult to injury?” Today, the cliché is used in a less literal sense to describe any action that makes a bad situation worse.

Albatross Around Your Neck

If you studied the Samuel Taylor Coleridge poem “The Rime of the Ancient Mariner” in English class, you may already be familiar with the phrase albatross around your neck. In the late-eighteenth-century literary work, a sailor recalls shooting a harmless albatross. The seabirds are considered lucky in maritime folklore, so the act triggers misfortune for the whole crew. As punishment, the sailor is forced to wear the animal’s carcass around his neck:

Ah! well a-day! What evil looks Had I from old and young!

Instead of the cross, the Albatross About my neck was hung.

Today, the image of an albatross around the neck is used to characterize an unpleasant duty or circumstance that’s impossible to avoid. It can refer to something moderately annoying, like an old piece of furniture you can’t get rid of, or something as consequential as bad luck at sea. Next time you call something an albatross around your neck, you can feel a little smarter knowing you’re quoting classic literature.

Forever and a Day

This exaggerated way of saying “a really long time” would have been considered poetic in the sixteenth century. William Shakespeare popularized the saying in his play The Taming of the Shrew (probably written in the early 1590s and first printed in 1623).

Though Shakespeare is often credited with coining the phrase, he wasn’t the first writer to use it. According to the Oxford English Dictionary, Thomas Paynell’s translation of Ulrich von Hutten’s De Morbo Gallico put the words in a much less romantic context. The treatise on the French disease, or syphilis, includes the sentence: “Let them bid farewell forever and a day to these, that go about to restore us from diseases with their disputations.” And it’s very possible it’s a folk alteration of a much earlier phrase: Forever and aye (or ay—usually rhymes with day) is attested as early as the 1400s, with the OED defining aye as “ever, always, continually”—meaning forever and aye can be taken to mean “for all future as well as present time.”

He may not have invented it, but Shakespeare did help make the saying a cliché; the phrase has been used so much that it now elicits groans instead of swoons. Even he couldn’t resist reusing it: Forever and a day also appears in his comedy As You Like It, written around 1600.

Happily Ever After

This cliché ending line to countless fairy tales originated with The Decameron, penned by Italian writer Giovanni Boccaccio in the fourteenth century. A translation of the work from the 1700s gave us the line, “so they lived very lovingly, and happily, ever after” in regard to marriage. In its earlier usage, the phrase wasn’t referring to the remainder of a couple’s time on Earth. The ever after once referred to heaven, and living happily ever after meant “enjoying eternal bliss in the afterlife.”

It Was a Dark and Stormy Night

Edward Bulwer-Lytton’s 1830 novel Paul Clifford opens with “It was a dark and stormy night.” Those seven words made up only part of his first sentence, which continued, “the rain fell in torrents—except at occasional intervals, when it was checked by a violent gust of wind which swept up the streets (for it is in London that our scene lies), rattling along the house-tops, and fiercely agitating the scanty flame of the lamps that struggled against the darkness.

Regardless of what came after it, that initial phrase is what Bulwer-Lytton is best remembered for today: an infamous opener that has become shorthand for bad writing. No artist wants to be known for a cliché, but Bulwer-Lytton’s legacy as the writer of the worst sentence in English literature may only be partially deserved. Though he popularized “It was a dark and stormy night,” the phrase had been appearing in print—with that exact wording—decades before Bulwer-Lytton opened his novel with it.

Little Did They Know

The cliché little did they know, which still finds its way into suspenseful works of fiction today, can be found in works published in the nineteenth century, according to writer George Dobbs in a piece for The Airship, but was truly popularized by adventure-minded magazines in the 1930s, forties, and fifties. The phrase was effective enough to infect the minds of generations of suspense writers.

Not to Put Too Fine a Point on It

Charles Dickens is credited with coining and popularizing many words and idioms, including flummox, abuzz, odd-job, and—rather appropriately—Christmassy. The Dickensian cliché not to put too fine a point upon it can be traced to his mid-nineteenth-century novel Bleak House. His character Mr. Snagsby was fond of using this phrase meaning “to speak plainly.”

Pot Calling the Kettle Black

The earliest recorded instance of this idiom appears in Thomas Shelton’s 1620 translation of the Spanish novel Don Quixote by Miguel de Cervantes. The line reads: “You are like what is said that the frying-pan said to the kettle, ‘Avant, black-browes.’” Readers at the time would have been familiar with this imagery. Their kitchenware was made from cast iron, which became stained with black soot over time. Even as cooking materials evolved, this metaphor for hypocrisy stuck around.

__________________________________

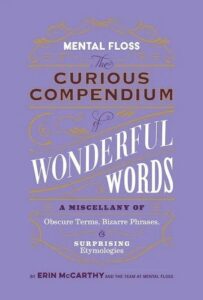

Excerpted from The Curious Compendium of Wonderful Words: A Miscellany of Obscure Terms, Bizarre Phrases & Surprising Etymologies by Erin McCarthy & the Team at Mental Floss. Copyright © 2023. Available from Mental Floss/Insight Editions.

Erin McCarthy & the Team at Mental Floss

Erin McCarthy is the Editor-in-Chief of MentalFloss.com, host of The List Show on YouTube, and the creator, executive producer, and host of Mental Floss's History Vs. podcast. She joined Mental Floss in 2012. Previously, she covered everything from natural disasters to bridge engineering to the science behind sci-fi movies for Popular Mechanics magazine. When she's not editing or writing, you can find her karaoking, reading non-fiction, watching Investigation Discovery and hockey (go NYR!), or hanging out with her cats, Oliver and Pearl.