Beauty and Terror: On Understanding and Accepting a Schizophrenic Mother

Nina St. Pierre Explores the Intersections of Spirituality and Mental Health

I was twelve. It was 1993 and we were in far rural northern California in a town called Weed that looked about like it sounded. It was winter, I think, which in 1993, still meant blizzards, and dirty snowbanks piled high at the edges of the road. In the distance, the sun set behind Mount Shasta, backlighting her ethereal silhouette in luminous oranges and pinks. Inside, I lingered outside Mom’s prayer-room door.

I could just make out the low hum of her voice on the phone. She’d been doing this more. Having hushed conversations behind closed doors. I pressed my ear closer to listen. “It’s a past-life thing,” she was saying. Her voice husky and conspiratorial.

When I was sure she’d hung up, I waited a beat, knocked, and walked in. A sliver of space between the bathroom and the stairs to my room, the prayer room was herd sanctuary—the only space in the house she’d claimed as her own. Every day, she’d slip away, shutting the hollow door to pray or chant or decree or whatever she was into at the time.

It’s easier to say goodbye to one part of a person you love than to accept that they could be, that they are, terror and beauty wrapped into one.

Technically, she was just on the other side of the door, but she was gone. In the place where we couldn’t reach her. The one I never fully understood. In the center of the room, was a patio chair draped with an afghan, where she sat to read. Along the windowsill, saint cards were lined up like family portraits: Joan of Arc; Archangel Michael; Saint Francis, the first Catholic stigmatic. Mom’s heroes weren’t girlboss CEOs or flamboyant artists or extraordinary homemakers. She venerated those who had or were willing to suffer for a larger purpose. Those who’d been misunderstood. Persecuted.

Religious texts and thrift-store esoterica were stacked against the walls like cairns. Books she’d schlepped from home to home in our constant moves: the Holy Bible; A Course in Miracles, a text “channeled” by Helen Schucman, the Columbia University psychologist who claimed Jesus spoke to her; Science and Health, the foundational text of Mary Baker Eddy’s controversial belief in mind over matter.

Sometimes, if she wasn’t in the room, I’d flip through whatever book was splayed open on her chair. Scanning arcane words she’d underlined—divine principle, material law, ascension, soul matrix—I tried to dissect them like a code. To find something that would explain where she went when she stopped talking mid-conversation, her sentences hanging in midair. She was studying the divine, and I was studying her—the scripture of a mother adrift. Trying to see where it might lead, and if I should follow.

In another life, she might have been a scholar.

In this one, I think she was reading to survive.

Twenty years later, my mother will be dead, and I, ravenous for data to steady my churning grief, will sit alone on the floor of Powell’s Book in Portland, Oregon, trying to answer the question seeded in her prayer room: Where did she go? I was looking back at my life with a new lens, now, with a theory—schizophrenia. The therapist said that she was pretty textbook.

Illness settled over the past like a ruby filter. As I tried to reconcile what I’d known then, with what I understood now, I became a researcher, an excavator, collecting facts, each one an edge piece to the puzzle. I scoured the annals of literature, psychology, science, and religion. Plumbed the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, mainstream psychology’s bible. I learned about schizophrenia from psychiatrists’ perspectives and from those who lived with it. I spent long dark days in a corner of the internet rife with sparkly, mispunctuated websites, which unraveled the complicated backstories of Catholic stigmatic’s, saints, and martyrs.

Now, it was me who was reading to survive.

Slowly, I was building a new lexicon and, from that lexicon, a new lens for understanding my childhood.

Astral travel could be dissociation.

Channeling, hallucination.

Past-life regressions, trauma flashbacks.

But one term really changed everything. Delusion.

The hallmark of a delusion is its imperviousness to debunking. No matter what facts or information are presented to the deluded person, what they believe, and experience, is the absolute truth. To disagree only agitates them and can render you irrelevant, or worse, cast you as an antagonist in their story. When delusions are clearly unreal—dreams of being married to a celebrity or seeing dragons, for example—they’re easier to distinguish.

But my mother’s stories were harder to pinpoint because they were about real people and tracked with the culture and environment that we’d lived in—one where mystics and liberations aligned at the foot of a cosmic mountain. While my adult reality no longer aligned with my mother’s, as a child, what she had believed formed the bounds of my own imagination. Much of what she shared; I took at face value. Even if something smelled off, I didn’t disbelieve that it was true to her. While for me, spirituality was a novel possibility; for her it was the way she saw the world.

I’ve had to forgive myself for what I chose not to see. For choosing myself.

Writer Esmé Weijun Wang, who has schizoaffective disorder, writes about how Western society has perceived the trajectory of the schizophrenic:

The story of schizophrenia is one with a protagonist, “the schizophrenic,” who is first a fine and good vessel with fine and good things inside of it, and then becomes misshapen through the ravages of psychosis; the vessel becomes prone to being filled with nasty things. Finally, the wicked thoughts and behaviors that may ensue become inseparable from the person, who is now unrecognizable from what they once were.

Toward the end of her life, my mother wrote me a letter: “My well-being is not your responsibility, sweet girl.” I broke down in tears when I read that line, because even though she’d never asked that of me—not, exactly—it felt like it was.

Because I couldn’t save my mother, I could not fully see her.

Even as a girl, some deep, survivalist part of me knew that if I stayed, I would have been consumed with helping; with fixing what was unfixable. What in fact did not need fixing but tending. Mental illness doesn’t always demand a solution. It’s not something to be “cured,” but accepted and supported and adapted to. The gap between her and I, the problem, was not her mind per se, but the schism between her reality and mine. Between her as mystic or mad. Between the life I saw as productive and the one allowed to her.

I’ve had to forgive myself for what I chose not to see. For choosing myself.

I’ll never know how many of her stories and struggles were real, and how many were imagined. But in her death, I was able to finally look at them, to turn them over in my hands and examine their many facets. Maybe all those years, in defining her visions via spiritual imagery and stories, she was reclaiming her vessel, rendering it “fine and good,” as per Wang.

Maybe the stigma of schizophrenia as split mind has been so persistent because it’s easier to say goodbye to one part of a person you love than to accept that they could be, that they are, terror and beauty wrapped into one. And maybe this is my work. Our work. To allow it all to exist at once.

__________________________________

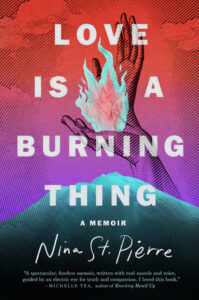

Excerpted from Love Is a Burning Thing by Nina St. Pierre. Copyright © 2024. Available from Dutton, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC.

Nina St. Pierre

Nina St. Pierre is a queer essayist and culture writer whose work has appeared in Elle, GQ, Harper’s Bazaar, Gossamer, Nylon, Outside, Columbia Journal, Bitch, Catapult, and more. She is a 2023 NYSCA/NYFA Artist Fellow in Nonfiction Literature. She holds an MFA in Creative Nonfiction from Rutgers-Camden.