Bathhouse Sex, DIY Sestinas, Steamy Surrealism, and Sonnets: New Poetry Coming in July

“Let’s be clear: this is no light ‘beach read’ stack.”

Bathhouse sex, DIY sestinas, steamy Surrealism, and sonnets, sonnets everywhere. Add a fiery debut from a press called Riot in Your Throat; James Allen Hall’s blockbuster (playing since March), Romantic Comedy; and Colin Channer’s latest–complete with a smoldering guitar solo, and July just might be the hottest month. (Yes, there’s a new Terrance Hayes collection, and leave it to him to make sestinas hot again.)

This month’s poets collectively offer a formal assuredness that I find refreshing. As one of the cut-up sonnets in Eric Sneathen’s Don’t Leave Me This Way concludes, “Our summer’s just begun.” But let’s be clear: this is no light “beach read” stack. These poets offer expert reckonings with larger histories of violence, displacement, and trauma.

*

Kathryn Bratt-Pfotenhauer, Bad Animal

(Riot in Your Throat)

This fierce debut ripples with death, including the murder of an elk, a moirologist (a professional mourner), an executioner’s wife, a student holding a corpse’s hand in a morgue, and the decline of a father—and this in just the first fifteen pages. What does the future bring? In “The Contract,” imagined motherhood, in “Prayer,” a speaker hoping not to be pregnant. Details such as a “squirrel with its toothpick ribs, / its chest torn open to the sky” and a decapitated bumblebee “the work of some angel, a hornet” reflect the poet’s steel-eyed sensibility as she addresses both bodily trauma—grief, sexual assault—and desire. Bratt-Pfotenhauer’s control allows her subjects to explode: this is a debut poet to watch.

Colin Channer, Console

(FSG)

“I was inked wicked,” recalls the speaker of Colin Channer’s Console in a poem portraying the shifts in a mother-son relationship over time. Whether stopping time in a first-person scene of a car accident, responding to photographs in evocations of place, or evoking “the shuddered wood, that deep flesh shook” of guitar, Channer forges a sound that echoes his experience as both dub bassist and novelist familiar with the rhythms of narratives and sustained voice, drawing on his Jamaican roots and “Grandma’s grit language.” Channer’s language play is embodied in the title: to console, yes, but also, concretely, the console used to mix music.

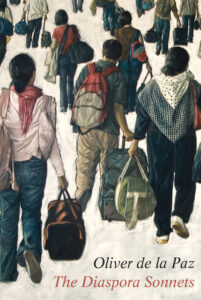

Oliver de la Paz, The Diaspora Sonnets

(Liveright)

One of Oliver de la Paz’s gifts is his sense of the book as a whole. In his latest, he turns the sonnet into a lens for slow-motion snapshots of migration, shifting between his parents’ former life in the Philippines to their family’s transient life in the States “moving from place to place, house to/ flimsy house.” Amidst poems rich in details of the resulting changing natural landscapes emerge vivid portraits: we see the father in his twenties holding a hatbox, later, a gun. Standout poems slip into the consciousness of a mother and the persona of a grandmother’s fears. Every “Diaspora Sonnet” holds this label as part of its title, the pointed repetition pounding impactfully, each section bookended by a “Chain Migration” ballad and a punctuating final pantoum, a reminder of these poems’ origins.

James Allen Hall, Romantic Comedy

(Four Way Books)

“Two weeks, and he hasn’t / hurt me yet, my swim coach lover, yelling / down into the water. I can’t love/ an incapable man. My body is a knife.” So ends “Swimming Lesson,” part of a devastating and sharp-witted collection in which Hall confronts family disfunctions and trauma as well as partner rape and abuse. In these poems, the mind is the knife. Hall knows his genres and how to disrupt them with allusions to film, a series of poems called “Genre Theory,” and a gift for telling stories in the small shots of the lyric, using the line break to rupture and repair in acts of queer survival. Yes, this is a March book, but isn’t summer the time for picking up that book you’ve been meaning to read, and that once you open, you can’t put down?

Terrance Hayes, So to Speak

(Penguin Poets)

Terrance Hayes’ newest collection delivers the formal vivacity and genius reminiscent of earlier ranging favorites like Lighthead. You will find returns (and mash-ups) of his much-imitated forms and even a few more “Sonnet[s] for My Past and Future Assassins.” Enter, too, the ekphrastic DIY sestina with a protracted envoi, as well as a powerful “ghazalled sentence” evoking Eddie Kendricks’ “My People,” while tackling the Negro Act of 1740. The poem’s repeated word: people. Inventive and incisive, Hayes proves once again that he can not only use the poem as a powerful tool, but look like he’s having a lot of fun doing so. You don’t need me to tell you to keep reading Terrance Hayes, but if you somehow haven’t picked up his books yet, what are you waiting for?

Joyce Mansour, Emerald Wounds: Selected Poems

(City Lights)

Emilie Moorhouse’s sharp, steamy translation of Syrian-Jewish poet Joyce Mansour moves from a 25-year-old Monsour’s 1953 debut Screaming—written in Cairo after having already lost a mother and a young husband—to her final poems written as an exile in Paris. Surreal incarnations of raw female power—erotic, rageful—permeate; the first poem delivers agony—“Your head removed from your slit throat / It is the beginning of eternity”—the second, an amazon “eating her last breast” before the gods, men, and tanks arrive.

Desire and fulfillment abound: Moorhouse’s translations capture both Mansour’s linguistic inclinations—“Tease his kinks with a silk brush”—and graphic surrealism—“my deep body, mindless octopus . . . . ” (You’ll have to read the poem to see what happens next.) Moorhouse’s instructive introduction aptly labels “erotic-macabre” this Surrealist celebrated by Breton but largely left behind and out of print until this valuable English translation, which includes the French originals.

Eric Sneathen, Don’t Leave Me This Way

(Nightboat)

“I wanted to hear the clamor of a phantasmic bacchanal echoing in the corridor of an ongoing emergency,” Sneathen notes in this book of sonnets shaped from cut-ups of archival texts, contemporary fantasies, and even safe-sex literature. There’s an (acknowledged) hint of Dodie Bellamy’s Cunt-ups, without the serial killer or cunts. Instead, male body parts and a heartbeat: meter, and the spirit of Gaétan Dugas, wrongly vilified as HIV/AIDS “Patient Zero” by Randy Shilts. From the salty, gorgeous fragmented segments of the opening section, Telemachy, to the slurping and fucking of a Dugas section that includes “He’s Someone in this Place, a Gay Orgy Coming” but also lesions, a clinic, the whole of an era—Sneathen artfully and archly builds something urgent, erotic, elegiac, and vitally archival.

Rebecca Morgan Frank

Rebecca Morgan Frank's fourth collection of poems is Oh You Robot Saints! (Carnegie Mellon UP). Her poetry and prose have appeared in such places as The New Yorker, Ploughshares, American Poetry Review, and the Los Angeles Review of Books. She is an assistant professor at Lewis University and serves on the Board of Directors of the National Book Critics Circle. She lives in Chicago.