Bad Religion’s Greg Gaffin on What the Early Documentaries Got Wrong About the Punk Scene

“Punk was becoming stereotyped as having no intellectual merits at all.”

Punk was ripe for exploitation. Outlandish desperados were all that was left of the scene. And these were seized upon by popularizers who were uninterested in telling a more compassionate or empathetic tale about the more worthy aspects of the genre. There are guys who wait their whole life for someone close to them to finally kick the bucket just so they can say, “He didn’t suffer fools” calculating bastards who memorize such phrases and use them opportunistically to inflate their own reputations without giving due credit to those who came before. Such artless saps love to throw shit at the wall and see who is interested in what sticks. This is what happened in the early documentary period of the punk scene in SoCal.

Certain promoters and people behind the scenes started telling stories about punk, and the consumers of mainstream media listened. Storytellers were emerging who were trying to make a business out of the punk scene. In the spring of 1984 my friend Phil invited me over to his recording studio, Spinhead Studios, one day after classes. His pal Dave, an aspiring filmmaker, often hung out there too, and he had just brought over something for us to watch on video. “There’s this new film coming out by BYO. It’s supposed to be about the scene from a couple of years ago. I’ve got a copy of it!” We watched together as the opening credits ran the title: Another State of Mind. “Cool,” I said. “I know these guys. Maybe it will be about something positive other than the violence and thuggery and drugs.”

The movie depicts a national tour by Social Distortion and Youth Brigade in 1982. Despite its good intentions—the band Youth Brigade was narrating throughout, interwoven with blurbs from other punks in scenes from other cities in North America—it failed to offer punks much hope for a unified intellectual narrative vision. In fact, as the movie went on, I got more and more disheartened. It starts off depicting a huge punk audience slam dancing over the narration of Youth Brigade’s singer, claiming, “This movie is about music by kids for kids,” which was bullshit because those kids on the film were not slamming to any music made by Youth Brigade. I’d been to shows by Youth Brigade. They couldn’t draw that many people to their shows.

So, strike one. I protested, “This isn’t even a Youth Brigade show, so why is he talking over this first scene in the movie as if he had anything to do with drawing those kids together?” Within the first two minutes the singer-narrator was revealing that some sort of mission is behind the counterfeit concert footage. He was singing the praises of his “organization,” the Better Youth Organization (BYO). “Jesus Christ!” I said. “This is a propaganda film?”

Next thing to catch my attention was an interview by one of my heroes, Keith, from the Circle Jerks. I respected Keith greatly. He inspired me. He wasn’t a “kid” and he didn’t write music for kids. He cowrote and sang some of the most important punk songs ever to come out of Los Angeles. But you wouldn’t have guessed that they even knew who he was. Not only did they fail to mention how important he was to the LA punk scene, they didn’t even list his affiliation with the Circle Jerks during his interviews or credits.

The film kept harping on how bands have to “do it yourself ” if you want to be heard. But the filmmakers showed the opposite strategy. They essentially asked for help from others to make their film! And they did so with no intention of crediting them. Is this really supposed to convince anyone that somehow this is an example of a “Better Youth” or “good” aspects of our punk scene? “This is turning into a real shit-pie,” I uttered.

And furthermore, “Better Youth Organization” sounded like some kind of eugenics nonsense. I was reading about the dangers of genetic experimentation and social engineering in my evolution classes. Real tasteless shit to anyone with an intellectual bent or knowledge of basic history. This, I chalked up to poor taste, but perhaps let it slide as artistic license. Strike two.

But where the movie finally struck out was when it showed a packed concert featuring images of the Circle Jerks and Bad Religion on stage but choreographed to the music of Youth Brigade over the footage. These were by far the most dramatic sequences of the movie: elated punk rockers dancing to music that they loved by the Circle Jerks and Bad Religion. Two band never mentioned in the film! The disconnect was that these images were accompanied by overdubbed music from Youth Brigade, a band that never elicited such enthusiasm nor drew that many punks to their shows. This rendered the entire project a sham piece of propaganda as far as I was concerned. “This is video plagiarism!” I yelled. “Is there such a thing?” asked Phil. I didn’t know, but it sounded good to me, and both Dave and Phil got a kick out of my film review.

I remembered the uncredited Bad Religion concert well. It was such an incredible turn out. Over a thousand punks, or so it seemed. I took a pause between songs to say to the large punk audience: “Let’s switch places. Everyone in the audience up on stage, and when we start the next song we will do the world’s largest stage dive!” (That moment is captured in the film at about forty-four minutes in.) At that moment we broke into our song, “We’re Only Gonna Die,” and mayhem ensued. I didn’t know that anyone was filming it, but I’m glad it was captured on camera because it’s one of the truly breathtaking moments of satisfaction I had onstage at that young age.

That song was played on Rodney on the ROQ and the entire punk community seemed to embrace it at the time of this particular concert. Unfortunately, by the time the film came out in 1984 it felt like whiplash. Not only were we uncredited in the movie, but the punk scene itself had devolved, and had shrunk to a fraction of its size. By that time, punk crowds that used to number over a thousand were now averaging around a hundred. The legacy seemed to be dying, and these storytellers seemed only intent on self-aggrandizement.

I felt then as I do today: If you’re trying to point out how “good” your community or your organization is, you should start by giving credit to those who helped build the scene that you’re claiming as your own.

This experience was par for the course. Around this time, there started a trend where self appointed punk experts began to outline their vision of punk morality. As if some kind of mystic rule book had been lying in wait for a prophet to emerge to decipher it and let all punks know the score. Like the attention given to televangelists and old-time religion, the mainstream media was only too happy to feature these teenage punk philosophers, and it came across as some kind of attempt to form a new religion. Sweeping statements. Bold generalizations. No data. “If you don’t fight society, society will win!” “You gotta do your own thing because nobody in this society will ever help you out.” It was something that would eventually build into a national pastime. Whoever had the camera on them could claim just about anything, and a certain portion of the viewers would believe it without question.

Punk was becoming stereotyped as having no intellectual merits at all. As if punk was associated with all of society’s ills, TV shows highlighted its ugliest aspects.

Some of us refused to listen to false mandates and knew how to spot them. But others failed to recognize propaganda. The propagandists themselves failed to realize that when they spouted off about what is or isn’t punk, they flunked Authority 101. Prescriptive thinking undermined their own oratory, and lost anyone with half a brain. Plenty of punks, it seemed, were all too happy to voice their beliefs and conscripts with the expectation that others would follow blindly.

Sadly, the unwashed masses didn’t want to do the work of learning how to think. They just wanted to be told what to think. There were all too many punk bands who craved such a following, any following. Sure, I wanted one too, but I preferred it to be a microcosm of society, a microcosm of the university, an enlightened bunch. For this, we had to assume we were playing to an intelligent audience and give them something to nourish their minds.

I wasn’t interested in hearing about my cohorts’ unexamined beliefs, and to be frank, I didn’t care if they thought I was punk or not. I clung to the notion that music was sufficient to express an interesting point of view, even a defiant one. If that was liked by punks, all the better. For many years, I wasn’t interested in doing any more interviews or sharing half-baked philosophy with the fanzines. I was content to acquire knowledge rather than disseminate it at that point in my life. Bad Religion was in the midst of a three-year hiatus between albums.

Neither I nor Brett wrote a single punk song. I was glad to be getting trained in informed opinion at the university, restricting my thinking, honing skepticism, trying to focus my thoughts and make statements validated by factual data. Read the independent thinkers. Intellectuals. Darwin and Haeckel, A. S. Romer and S. J. Gould, Ernst Mayr and E. O. Wilson, Sagan, Bronowski and Leakey, Chomsky and Hardin, Hesse and Nabokov, Kesey and DeLillo. Seers. Masters of their disciplines. They’re who I admired, and their achievements in arts, letters, and science were aspirational motivation for me.

Punk was becoming stereotyped as having no intellectual merits at all. As if punk was associated with all of society’s ills, TV shows highlighted its ugliest aspects. The Phil Donahue Show, the popular daytime talk show, featured punk runaways and downtrodden kids. CHiPs, the nation’s top primetime police drama, featured punk criminals. Even the feature film The Decline of Western Civilization by Penelope Spheeris focused more on the violence, nihilism, and teenage rebellion rather than making any kind of coherent sense of the film’s title.

I watched the movie wishing to hear more songs, see more performances from my favorite bands, but instead had to sit through interviews with punk scenesters, many of whom were acquaintances, being elevated in their portrayal as some sort of philosophers. It was totally depauperate of intellectual focus. And most disappointing, the bands were portrayed to look more like a freak show and less like an artistic community cemented by great music.

Nowhere in these films or features did they talk about punk as being musically and lyrically compelling. They failed to touch on what made punk so attractive that it could fill concert halls just a couple of years ago but now struggled to fill small clubs.

The punk follow-up by Spheeris, Suburbia, wasn’t any better at adding either nuance or general interest to the punk scene. It merely capitalized on and hastened the formation of a seedy, negative stereotype. Loosely scripted, actual kids from the punk scene (rather than trained actors) were asked to act out scenes in the telling of a story about homeless teens in the Southland. Drugs, alcohol, family dissonance, runaways, and so forth. I felt like screaming when I saw it: “Yes! We get it! But what does punk have to do with it?” These things are so commonplace in American life that I suspected that the director was simply exploiting the kids on screen. Getting them to “play themselves” in roles that were stereotyped was just sad to me.

But nothing saddened me more than the onscreen image of André, that kid with the wooden leg who Wryebo and I befriended as schoolboys back in Racine. All his youthful exuberance gone. Now he appeared as one of the film’s characters, a drug-addled runaway being exploited for his disability under the thinly veiled premise of storytelling. He was playing himself, but was being used as a symbol of an incorrect and unflattering stereotype.

Even though I had lost touch with him a lifetime ago, I still felt a sense of friendship and loyalty, and I believed that he deserved better treatment. We made friends as mere tots according to the dictates of our academic upbringing. Due to the strong urging of our mothers (the administrators), we befriended André in the spirit of humanistic, compassionate values that they instilled. What I saw on screen was a breach of humanism, a glorification of vulgarity.

I always found it puzzling that Black Flag was depicted by Spheeris as some sort of deeply philosophical cult. The truth is, a punk had to make a choice when he decided to go see them play. While the cops were busy bustin’ heads outside the venue, inside was a parallel, unconscious, contradictory absurdism only apparent to the thinking person. Black Flag concerts always were dressed with a one-man police force—a roadie named Mugger, crouched in front of the band, mad-dogging the audience, daring any punker to test his might and come up on stage for a celebratory stage dive.

“Not on my watch” was the posture of this most famous bodyguard of the LA punk scene. Getting punched in the face for wanting to stage dive was somehow deemed acceptable by many punkers at the Black Flag show. So, basically, if you weren’t getting clubbed in the head by the LAPD outside the venue, you risked getting punched in the face by Mugger inside at the concert. None of this was touched on in The Decline.

Nowhere in these films or features did they talk about punk as being musically and lyrically compelling. They failed to touch on what made punk so attractive that it could fill concert halls just a couple of years ago but now struggled to fill small clubs. They didn’t give enough attention to the essence of what made the SoCal scene unique: the multitude of bands that sprung from the Southland and the songs that made them great. The music was in a quagmire. Bands stopped writing good songs. So began a period where preaching about proper conduct in the punk scene overshadowed the music of the scene. Punk went into a sort of hibernation.

________________________________________

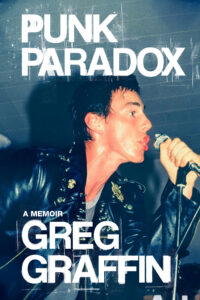

Excerpted from PUNK PARADOX: A Memoir by Greg Graffin. Copyright © 2022. Available from Hachette Books, an imprint of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

Greg Graffin

Greg Graffin is the lead singer and a songwriter in the punk band Bad Religion. He obtained a masters and Ph.D. in Zoology at Cornell University and a masters in Geology from UCLA. He has lectured at UCLA and Cornell where currently he teaches evolution. He is also the author of Evolution (with Steve Olson) and Population Wars. When he’s not on tour, he's with his family at places he considers home: upstate New York, Southern California, or Wisconsin.