Back to School for Everyone: The Literature of Obsession with Julia May Jonas

On Transformation, Destruction, and Catharsis

To propose a class titled The Literature of Obsession is nearly as broad a topic as proposing a class simply titled: literature. There is an argument that every novel is a novel of obsession, or at least preoccupation, if one is able to identify just what the novel, the author, and/or the characters are obsessed or preoccupied with.

However, from both a practitioner’s perspective, as well as a reader’s, it can be a highly useful exercise to identify and read a text through the lens of obsession, because obsession functions in literature in the same way that forced perspective functions in Renaissance painting: it leads us through what is being shown while simultaneously allowing for a full world to exist around, alongside, and in the background of the subject.

To put it more simply, obsession can provide the focal point and drive for a novel, which—if it is worthwhile—is never about simply one thing, but which also must resist a kind of diffusion that makes us think, “What is this about?” (Naturally, there are no musts in literature, nor does a book have to be “about” anything. However, successful books, even if they resist “about-ness,” tend to have a clarity of vision, and the ability to communicate their intention to the reader.) Obsession tends to give us, as readers, a tow line to hold on to, providing the ability to relax and take in the scenery around us while knowing that we are headed in some direction, however obscure or mysterious that direction may be.

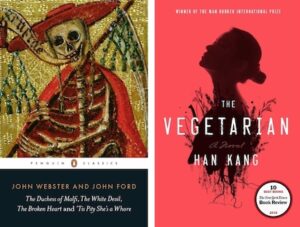

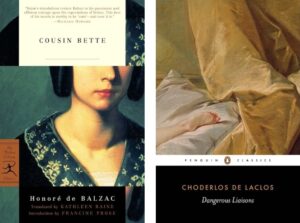

That said, the novels (and play) in this course tend to wear obsession on their sleeve, and each unit explores different ways obsession could function, be it formally or thematically. In the Obsession as Transformation unit, Ferdinand in The Duchess of Malfi is seized with such conflicted desire for his sister that he develops lycanthropia: transforming, for all intents and purposes, into a wolf. In Obsession as Destruction, Cousin Bette’s longing for revenge against her extended family leads to ultimate decimation, shining a light on the corruption and hypocritical religiosity of the French society as Balzac saw it.

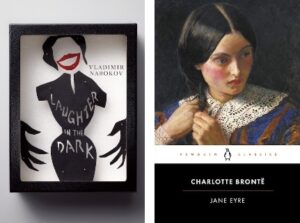

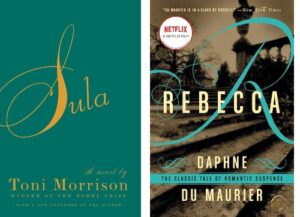

In Laughter in the Dark—our novel for the Obsession as Catharsis unit—Nabokov uses Albinus’s obsession for Margot as a form of hamartia, writing a novel according to the Aristotelian principles of tragedy, complete with a deeply ironic ending. In Obsession as Projection, the assumptions and judgments that Morrison’s Nel place on the character of Sula serve as a mirror—reflecting not only Nel, a Black woman in the early 1900s, nor Sula, but the mores, prejudices, sufferings, and strengths of her community.

Books of romantic obsession tend to tell us about the status of society and the individual: Giovannni’s Room, by considering David’s impossible love of doomed Giovanni, talks to us about western conceptions of homosexuality in the 1950s. Thirst for Love, written around the same time, concerning a widow’s fixation with her father-in-law’s servant, tells us about the status of women in Japan. Objects, in turn, reveal character—read the titular character’s quest for a home (stability and a sense of belonging) in A House for Mr. Biswas. And finally, for a post-modern twist, Markson’s masterful Vanishing Point gives us an obsessive form: ordered and meticulously arranged fact after fact that builds resonance and meaning, telling a story of the humanities, and in turn, humanity.

Course Description

The great paradox of obsession as a mental state is that it is both generative and destructive. Happily, these opposing forces, creation and destruction, create the ideal circumstances for a novel. In this course we will explore ideas of obsession, analyzing how they might function as a galvanizing concept in a variety of literature.

Reading List

Obsession as Transformation

John Webster, The Duchess of Malfi • Han Kang, The Vegetarian

Obsession as Destruction

Honore de Balzac, Cousin Bette • Pierre Choderlos de Laclos, Dangerous Liaisons

Obsession as Catharsis

Vladimir Nabokov, Laughter in the Dark • Charlotte Bronte, Jane Eyre

Projected Obsession

Toni Morrison, Sula • Daphne du Maurier, Rebecca

Romantic Obsession

James Baldwin, Giovanni’s Room • Yukio Mishima, Thirst for Love • Iris Murdoch, The Sea, The Sea

Object Obsession

V.S. Naipaul, A House for Mr. Biswas • Nathanial Hawthorne, The Scarlet Letter

Obsession as Form

David Markson, Vanishing Point • Nicholson Baker, The Mezzanine

Julia May Jonas

Julia May Jonas is a writer of fiction and plays and founder of the theater company Nellie Tinder. She has taught at Skidmore College and NYU and lives in Brooklyn with her family. Vladimir is her debut novel.