Ayşegül Savaş on the Work and Career of Turkish Writer Tezer Özlü

"Her voice was uniquely her own: consciousness distilled into narrative form.”

I first read the works of Tezer Özlü in my mid-twenties, in the years when I knew that I wanted to be a writer but didn’t yet know what I should write, nor what sort of “identity” I must take on. I wondered constantly what it meant for me to be a Turkish writer—whether it came with any responsibilities or particular subjects. It seemed, in those years when I read voraciously, that I was always reading the wrong things; that the books closest to my heart were somehow random rather than belonging to a literary lineage, and that I, their reader, wouldn’t belong anywhere in my writing, either.

I was feeling particularly adrift, having just moved from California to Paris, and soon enrolled to audit a university class in Turkish literature in an effort to fit myself into some kind of tradition. I was familiar with most of the texts though I didn’t have any sort of feeling for them. And it was precisely for this reason that I thought I should take the class: to grow a bond—surely a more vigorous one from my vast and haphazard reading of books that I was drawn to without design.

One half of the class comprised second-generation Turkish students who seemed to be there for an easy grade; the other half studious, unsmiling linguists. The reading materials unravelled steadily, each writer connected to the next, building an impenetrable wall of influence and fraternity, into which I had to try and wedge myself; from whose edifice scrape off my own influences.

If literature is also a map of human experience, then certain experiences are conspicuously absent from the canonical landscape.All writers are part of a literary lineage, of course, though these lineages are rarely neatly marked, even if it appears that way in retrospect, from texts that constitute a national canon. If literature is also a map of human experience, then certain experiences are conspicuously absent from the canonical landscape.

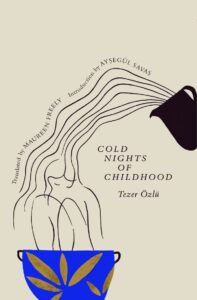

The first work of Özlü’s I read—in my “free” time from class reading—was her second novel, Journey to the Edge of Life, a metaphysical travelogue in the footsteps of Özlü’s favorite writers: Italo Svevo, Franz Kafka and Cesare Pavese. I found it refreshing that this Turkish author had chosen her own writers to follow, breaking away from the great wall of texts. When I read Cold Nights of Childhood next, it confirmed for me that her work didn’t belong to any school or style, that her voice was uniquely her own: consciousness distilled into narrative form.

*

Cold Nights of Childhood is Özlü’s first novel, and the second of three books she published in her short lifetime. She died of breast cancer at the age of forty-three in Zurich, a death even more tragic, perhaps, after years of battling with mental illness. Yet her small œuvre has always had a devout following, especially among young Turkish readers, for its madness, its honest sexuality, its lack of national fervor and its individuality.

It is surprising to me that Özlü’s work has not been translated into English until now but this translation arrives at a time when women’s writing of the self is experiencing a golden age: finding its place among a wider readership not as the representative of a national ethos, but rather of particular lives, nonetheless universal in its attention to daily experience.

The book shares many similarities with its author’s life. Born in 1943, Özlü studied at St. George’s Austrian High School in Istanbul but dropped out in her final year to hitchhike around Europe. In Paris, she met the actor and playwright Güner Sümer at the Montparnasse café Le Select and was married to him for a short period.

In her late twenties, she was treated in various psychiatric hospitals in Ankara and Istanbul for bipolar disorder. She was friends with prominent writers and artists of her generation, many of whom she met through the social circles of her brother, the writer Demir Özlü, who was arrested during the 1971 coup d’état, one of three that Tezer would witness in her lifetime. She got married again, this time to the film director Erden Kıral with whom she had a child. (Özlü would marry for a third and final time as well, shortly before her death.)

While these facts of Özlü’s life story overlap with the events of Cold Nights, the interest of the book is not so much its autobiographical mirror but the way that life is endowed with an electric mutability. Madness, after all, disrupts the temporal narrative. Here, time is broken and reshuffled through the sharp-edge of consciousness. The self is peeled away layer by layer to arrive at its core: “Then slowly, very slowly, I begin to remember. Myself. This is me. I am twenty-five years old. I am a woman. I am living through the second part of the madness that begins with joy. I have suffered the anguish of lethargy.”

In a letter to the writer Ferit Edgü, from the period of her frequent depressions and psychiatric treatment, Özlü offers a glimpse of what will become her first novel: “I’m alone here. I’m listening to Bach. Not that I’m really listening. Here there is only me. Or maybe someone who wants to appear like me. Everything is entangled in my mind. My childhood. The province. Men. Boredom. But my mind is completely empty. I have never been so lonely and so at ease. Completely empty.”

The book’s settings bleed into one another. At one moment we are in Berlin, the next, entering a hospital in Istanbul. The narrative jumps between interiors, all of them architecturally precise, cluttered with furniture. (Yet for a book that moves through so many interior spaces, Cold Nights is adamantly undomestic). There is a sense of walls closing in, of being entrapped, so that it matters little what city of what country we are in.

Once again, the experience is that of the essential “I,” wholly independent. There is no attachment to any place; Istanbul, Ankara, Berlin, Paris are all observed from the same remove, without nationalist feeling and without awe for Europe. The narrator subtly mocks her husband’s fawning admiration for Paris: “The man I’ve married begins to show his true face. His one and only world is Paris. Paris! Paris! Paris! […] But now he’s in Ankara. Deprived of Paris, he’s still resentful and getting worse. But the idea remains as fixed as ever: Paris is the city of his deliverance.”

A similar coolness comes across Özlü’s letters from Europe. To her friend, the great feminist writer Leylâ Erbil: “I have time to think about many things. I’ve met lots of writers. Almost all Latin American writers. All the Germans. Others through the DAAD [German Academic Exchange Service]. Many of them are mere fluff…Octavio Paz isn’t a more intellectual person than you and me.”

But too much independence is also detachment. The narrator is so staunchly an individual that she cannot seem to anchor herself in the world. She floats from the cold nights of her childhood to school, to Europe, to marriage and divorce, never quite able to shake off the seed of loneliness that sets her apart. Is this her condition, or that of society? Is it her inability to belong, or society’s rejection of those who do not fit its mold? Her family and friends offer sympathy at a distance but ultimately hand her over. Again and again, she finds that she has been brought back to a hospital, though she wishes those around her to understand that madness is contagious, and that she will only get worse among the sick.

*

The novel bears echoes of the political turmoil of the 1970s, leading up to the 1980 coup d’état (during which Özlü’s brother was denaturalized). Still, the unrest never comes to the foreground, or rather, does not warp the young woman into its own flow: the narrator is located in her mind, in the back-and-forth swing of sanity. It is worth noting just how radically unpolitical Cold Nights would have appeared in the fraught years of its publication, amidst the mainstream of political engagement that defines the literature of Özlü’s contemporaries.

Still, the book isn’t indifferent to the country’s situation. (Özlü’s own daughter, Deniz, was named after the revolutionary Marxist student Deniz Gezmiş, who was executed by hanging in 1972.) The lack of engagement is, rather, a frankness, the un-self-glorifying honesty particular to Özlü’s prose, and increasingly alien to contemporary auto-fiction so concerned with one’s own image, and the presentation of an exceedingly moral and moralizing self: “It’s the spring of 1971…In a year blighted by political unrest across the land. Unrest I shall never quite manage to understand. During the months of April and May, I am more cut off from the world than ever before.”

It is with the same frankness that Özlü writes about sexuality, neither sensational nor metaphorical. The book’s catalogue of orgasms (from early childhood to the novel’s final image) is once again daring, not just because of its writer’s cultural milieu but alongside the socially engaged works of her contemporaries.

But “daring” is perhaps not entirely just. After all, there is nothing outwardly defying in Özlü’s writing of sexuality. It is neither confrontation nor bravado, but an examination of an essential state. Perhaps what is daring is that the book can strip us of our assumptions of what a woman, and an artist, can and cannot write, given her time period, her country, her political context.

I had enrolled in the Turkish literature classes hoping to find out what sort of topics I should inherit, not knowing yet that the greatest challenge for a writer was the ability to discern her own curiosities. In my first encounters with Özlü’s work, I considered that it was an outlier, a one-off voice that had broken away from the great wall to follow its writer’s obsessions. Yet, this is also the mark with which all literature must be distinguished: the unique investigation of what it is to be alive, riding the current with open eyes.

On Sundays…these days…if I am strolling down an alley…and catch sight of a father in pyjamas…or if, on a grey and raining winter day, I see smoke rising from a stovepipe…and windows fogged with steam…if I look in to see laundry hanging up to dry…if the clouds are almost low enough to touch the damp bricks…if it’s spitting rain…if I hear live football matches blaring from every radio…all I want is to go, go, go, and keep going.

__________________________________

From Ayşegül Savaş’ introdiction to Cold Nights of Childhood by Tezer Özlü (translated by Maureen Freely) by Transit Books, available in May 2023. Preorder here. Excerpt reproduced with permission from the publisher.