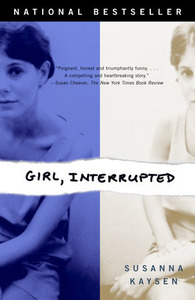

Author Susanna Kaysen Revisits Girl, Interrupted 30 Years After Its Publication

“There was enough blank space in it for people to insert themselves.”

It was while I was writing a novel about an anthropologist in a northern archipelago that I conceived of this book. The anthropologist was doing a village study: an analysis of the alignments and organization of a small, self-contained place. The novel was based on my own experiences of living in the Faroe Islands with my husband, an anthropologist who was doing research for his PhD thesis.

It came to me one day in the midst of working on that novel that I had lived in another small, self-contained place and had observed its alignments and hierarchies, its customs and special language. I intended this memoir to be my own village study.

Partly that was a way to distance myself from the sad fact of the matter—that I had been a patient in a mental hospital, not a Harvard graduate student doing his fieldwork. Probably, also, I was competing with my by-then-former husband.

It now seems to me that both the novel and the memoir were attempts to wrest my story out from under his story, which had brought him degrees and certifications I could never achieve. I wanted to tell my version of our village in the Faroes in my novel about the anthropologist, and then tell a story about the hospital that showed that I, too, was an anthropologist.

I finished the novel and embarked on this memoir.

I didn’t want to write about myself. Ridiculous! Who could write a memoir without writing about herself? I didn’t want to describe the events that had taken me to the hospital, or go into my family details, or admit to the terror I felt when all of a sudden I was locked into an institution on a spring afternoon. I was determined to maintain my anthropological stance. I thought the book itself—the fact that I had written it—would demonstrate the truth of the objection raised by every mental patient: I don’t belong here! I’m not crazy. Therefore I left a lot out.

The girls who cut themselves, the boys who just didn’t ever fit in, the promising young woman on her way to a career in law who couldn’t get out of bed one day and stayed there for a year—they all saw something familiar in this book.

This may be one explanation of why the book found so many readers. There was enough blank space in it for people to insert themselves.

It was surprising to me how many people had been in a mental hospital or had what used to be called a nervous breakdown.

There were just as many whose best friend or brother or child had gone through that sort of thing. Back then, this was not a topic for discussion, rather something to be kept secret. I got letters from people who said I had described their experiences.

When I gave readings at bookstores, people came up to me afterward to tell me I had written their story. Often, they thanked me for my courage.

Under the mistaken impression that I hadn’t written about myself, I always told these people that I wasn’t brave and that courage hadn’t been involved in it.

But they knew better than I did.

The girls who cut themselves, the boys who just didn’t ever fit in, the promising young woman on her way to a career in law who couldn’t get out of bed one day and stayed there for a year—they all saw something familiar in this book. That familiar thing, I think, was a person adrift, frightened, overwhelmed by existence and unable, for the moment, to engage with making a life for herself.

Not, as I liked to tell myself, an objective, dispassionate observer.

A lot has changed in the decades since this book was published, and even more since I was in the hospital. People aren’t locked up for years these days. I can’t say whether that’s a good thing or a bad thing. And perhaps the stigma of depression and “mental illness” has diminished somewhat. But suffering doesn’t change.

This book, written under a delusion, brought many readers some comfort. I hope it still has that to offer thirty years later.

__________________________________

From an introduction to the thirtieth anniversary edition of Girl, Interrupted. Used with the permission of the publisher, Vintage. Copyright © 2023 by Susanna Kaysen.

Susanna Kaysen

Susanna Kaysen has written the novels Asa, As I Knew Him and Far Afield and the memoirs Girl, Interrupted and The Camera My Mother Gave Me. She lives in Cambridge, Massachusetts.