At Play in the Uncanny Valley: on Monkeys as Literary Device

Or, How to Make Your Fiction Just a Little Bit Weirder

We all have the tendency to see human thoughts and feelings in animals. But well beyond anthropomorphism, animals in fiction (and in children’s stories especially) are more often than not slotted into stereotypical expectations by species: the sly and self-serving cat, the eager and loyal dog (though different breeds get their own sub-categories of personality, from the aloof poodle to the sad basset hound), the dopey bear, the conniving fox, the evil and criminal rat, the idiotic chicken, and so on. Monkeys are traditionally clever, mischievous troublemakers, with Curious George being the prime example, even though he appears to be a baby chimpanzee (no tail), which is to say an ape, and not a monkey.

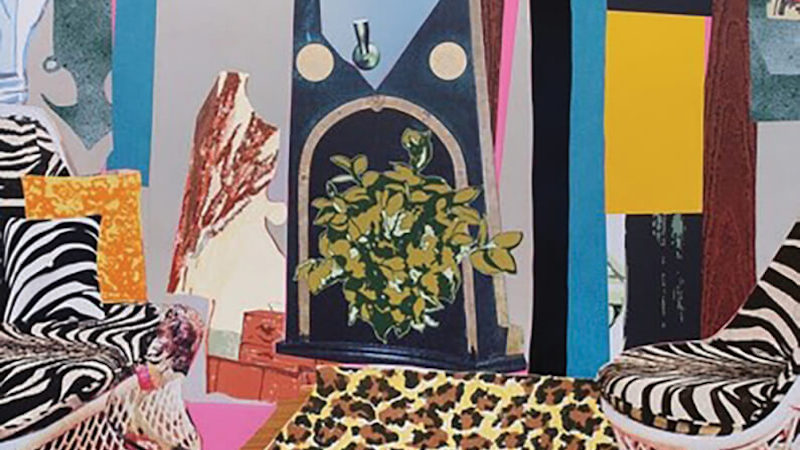

There’s a monkey in my new novel Still Life With Monkey. Ottoline the capuchin helper monkey, though she has no words—only hoots and chirps—has a lot to say. She makes things happen. In the E.M. Forster sense of a round character, a complex individual with the capacity to change, develop, and affect other characters and the events of the story in perhaps surprising ways, she is truly a significant character in the story. She is a catalyst, a vector, a mirror, for the main characters in my novel. When a monkey occurs in a work of fiction, there’s a small but significant shift, in that moment, for the reader. Even the idea of a monkey in a work of fiction provokes response. The uncanniness of the small humanoid face and little hands, combined with the distinctly non-human size and agility, plus the prehensile tail—it’s a moment when the reader is on notice that something non-quotidian is happening in these pages.

In 1919, Freud first defined “the Uncanny” as something that is at once frightening yet familiar. (The German word unheimlich can mean both “familiar” and “unfamiliar,” and translates into English as “uncanny.”) The “uncanny valley” is a concept first described in 1970 by Japanese roboticist Masahito Mori, who tracked the responses of subjects to images of human faces of increasing realism, which evoked feelings of increasing empathy, right up to a point where the likenesses were nearly photographic and real-looking. At that point, most subjects had a sudden reaction of repulsion. (The sudden dip in graphs describing their response gave the phenomenon its name.) Monkeys, with their not-quite-human faces, exist in fiction in this “uncanny valley.”

“Even the idea of a monkey in a work of fiction provokes response. The uncanniness of the small humanoid face and little hands, combined with the distinctly non-human size and agility… it’s a moment when the reader is on notice that something non-quotidian is happening in these pages.”Monkeys or apes in one form or another often appear as powerful agents of change in cherished classic fantasy novels. The sinister winged monkeys deployed by the Wicked Witch of the West were not cinematic inventions; if anything, they are even scarier in the pages of L. Frank Baum’s first Oz book, The Wonderful Wizard of Oz (1900). The Last Battle (1956), the final volume of C.S. Lewis’s Narnia Chronicles, features a despotic ape with the curious name Shift. (Paradigm shift? Perspective shift? Shiftless, shifty?) Shift dresses a donkey in a lion’s skin, to create a counterfeit Aslan, which he uses to mislead the denizens of Narnia to the point of catastrophic destruction. Both Baum and Lewis depended on the uncanniness of these evil creatures to enact the worst kind of human impulses.

In Flannery O’Connor’s marvelously difficult and weird “A Good Man Is Hard to Find,” though the story is manifestly focused on the danger of the at-large Misfit, and the grandmother, and the spectacularly gruesome landing point of the story when the most unlikely and worst thing that could happen actually does happen, there is a frisson of doomy strangeness earlier, when the traveling family arrives at Red Sammy’s restaurant and there is “a gray monkey about a foot high, chained to a chinaberry tree.”

Nothing goes anywhere with this monkey. He disappears into the branches of the chinaberry tree as the family walks into the restaurant. When they go back to their car, there he is again, “busy catching fleas on himself and biting each one carefully between his teeth as if it were a delicacy.” He has a limited existence, and not much agency in this story. He’s chained to a tree in a spot where he doesn’t really belong at all. And that’s it, done with the monkey. But his weird—yet muted and unremarked-upon—presence has been a herald of the strange possibilities that lie ahead. If there’s a monkey chained to a tree outside a diner, maybe the escaped convict on the front page of the newspaper could show up next. Anything could happen and does.

Richard Ford’s “Rock Springs,” another short story I like to discuss with my writing students, gives us the no-account Earl, a car thief known to write the occasional bad check. We meet him as he is driving a stolen Mercedes south, out of Montana, with his daughter Cheryl and her dog Little Duke in the backseat, his girlfriend Edna beside him. As Edna pours herself a drink, she blurts out, “Did I ever tell you I once had a monkey?” She proceeds to describe over several pages how she won the nameless little spider monkey in a dice game, but then after a week with it she “got the creeps” and couldn’t handle the way the monkey loomed over her, staring at her face while she slept. She describes trying to solve the issue by taking “a length of clothesline wire” with which she “wired her to the doorknob through her little silver collar” before going back to sleep. And then when Edna woke, she discovered that the monkey “had tipped off her chair-back and hanged herself on the wire line.”

It’s a horrifying story, all the more disturbing because of the understated way Edna tells it, right up to a description of putting the dead monkey into a trash bag and leaving it at a dump. And then Earl responds to this story by saying, “Well, that’s horrible, but I don’t see what else you could do. You didn’t mean to kill it. You’d have done it differently if you had.”

The sad little hanged spider monkey in “Rock Springs” is a minor note, to be sure, just as the gray monkey outside Red Sammy’s is a minor note in “A Good Man is Hard to Find.” But both monkeys notify the reader that strangeness lies ahead in the uncanny valley, where you can cross paths with the escaped convict from the front page of your morning paper or win an unlucky spider monkey with a roll of the dice.