As Much Power As the President: How Billionaires Became More Influential than World Leaders

Rob Larson on Income Inequality, Blurring Class Distinctions, and How Money Became Synonymous with Power

Broadly, an observer of the economy can make out a number of social and economic levels, based not only on how much money people have but how they make their living. This book has so far covered the economics of the richest households, whose members may work, and often earn gigantic CEO incomes from managing large corporate entities.

But primarily the household incomes of these families are made up of income from property—dividends on stocks, rent on residential or commercial properties, interest income from big cash deposits, and capital gains from corporate stock buybacks.

This is the crucial distinction between the rich, or the owning class, and the rest of us. Most of us make our money from working, but for the rich this is only sometimes the case. The ability to not just have a giant income, but to have a giant income from assets your family already owns, is an economically existential distinction.

This position of ownership of the productive economy, and the social and political power arising from that, is what defines the ruling class, and it goes back centuries to the advent of capitalism in the enclosure movement.It’s crucial to recall the numbers on stock ownership, where the richest one percent of households owns forty percent of traded corporate stock, and the top ten percent owns eighty-four percent. This position of ownership of the productive economy, and the social and political power arising from that, is what defines the ruling class, and it goes back centuries to the advent of capitalism in the enclosure movement.

Economist Douglas Dowd recalls the origin of capitalism in “the exploitation of workers whose farming land had been commodified by “the enclosure movement.” Those who had worked the land, free but far from rich, were swept off the land…and were transformed into desperate and powerless laborers.” The land became private property, its new owners the ruling class.

Below the elite are various economic echelons that people often enjoy smooshing together into a vague “middle class.” Historically, analysts on the Left have called the rest of society the “working class,” which has the advantage of suggesting something important—most families pay the bills by working, earning wages per hour or salaries per year in exchange for labor.

The kind of labor varies greatly, but from elite software coders to sewer maintenance workers, work is being done for an employer in order to make a living.

However, many people—especially those who don’t want anyone to focus on the monumental wealth and power of the rich—prefer to blur this simple distinction. While conservative supporters of capitalism and “free enterprise” enjoy claiming they oppose vague “elites,” these elites usually turn out to be various nonconservative middle-class people, like college professors and media figures. An actual billionaire may be thrown in if they aren’t conservative, like George Soros or Tom Steyer.

A century later, PC operating system monopolist Bill Gates said, “Of course, I have as much power as the president has.”These voices also like to suggest the main class difference is between blue- and white-collar work, roughly manual labor and intellectual work. And indeed, there is a dramatic difference in the daily work lives of a worker manipulating a spreadsheet in a climate-controlled office and a blue-collar worker toiling to clean a hideous “fatberg” of congealed material in a sewer under our feet, or climbing overhead to mind-bending heights on cell phone towers taller than skyscrapers with little protection.

But for all their major differences, blue-collar and white-collar workers all have one pivotal thing in common: the threat of a pink slip. Anyone working for one of the enormous companies that dominate most economic sectors can be laid off in the event of a recession or other retrenching, no matter how important your work is or how well you’re paid for it.

The exact details of how to define classes remains a fluid debate. But fundamentally, anyone in the white-collar or blue-collar working class, however exactly you define them, is at the mercy of the boss and the company’s quarterly profit-per-share targets.

This is why class is a useful concept; as researcher Katie Quan has said, “Not to think in terms of class is unfortunate, since no matter what our ideological persuasion may be, class analysis gives us a way of viewing the world that identifies power relationships. It clarifies who has power.”

Class shouldn’t be so controversial—capitalists talk about it all the time. When told one of his schemes to crush competitors was illegal, early railroad monopolist Cornelius Vanderbilt memorably said, “What do I care about the law? Hain’t I got the power?”

A century later, PC operating system monopolist Bill Gates said, “Of course, I have as much power as the president has.”

______________________________

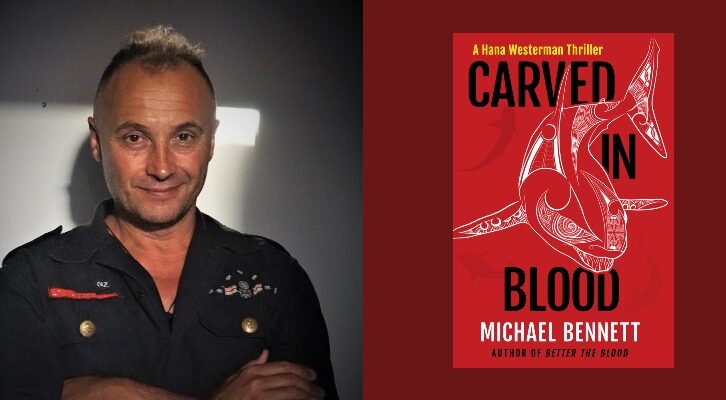

Mastering the Universe by Rob Larson is available via Haymarket Books.