A dream visits me from time to time like a recurring fever. Each version differs slightly from the last. Sometimes the woman’s scarf is made of silk or wool or a very delicate gauze, but it’s always black and white, and very long, with wavy stripes, and very docile to the wind.

A man arrives by plane after a short flight and walks towards the roundabout in front of the airport in Sainte Ercienne. Often, I have no idea who the traveler is; often, as is typical in dreams, I know and I don’t know, and even without knowing who he is, I have no doubt that he’s me. Next to the roundabout, where there are three or four small trees, spices, and other aromatic herbs in flower beds like in the well-manicured gardens of a medieval cloister, Eleonora, with a convertible beside her, is standing waiting for me, wrapped in her scarf.

We hardly speak. Afterward we drive along a hilly path where one can see the rust-colored crowns of the chestnut trees. Gusts of wind send Eleonora’s scarf floating in the air. This happens several times, until finally the scarf catches in one of the wheels, and Eleonora is torn violently from her seat, and I with her. We crash into the side of the hill, and I notice that my blood stains her lifeless face.

Curiously, the model of the car varies. Eleonora, whom I’ve only met in dreams, is usually dressed in different ways but she always wears the scarf. One time I caught the vaguest glimpse of the house that awaits us and at which we never arrive: it has vast stone terraces and overlooks an ocher-colored vineyard. Little by little I have been falling in love with Eleonora. That she doesn’t actually exist used to terrify me. Since then, I’ve learned that dreams are made of a substance no less consistent, true, or concrete than our mellifluous everyday reality. What’s more, perhaps there’s a parallel hell where we’ll pay for the sins we commit in our dreams. And, conversely, a paradise.

That love leads us to death, time and time again, hardly matters. From the moment I get off the plane, I see her standing there, calmly waiting for me. A happy silence affords us a secret, seemingly timeless form of love. We never know we’re going to die, or maybe we do, we know but we don’t say it, because only in silence can we recall the names of the aromatic plants that fill the roundabout in Sainte Ercienne, and, after having listed them and evoked their scents, we die again.

When anguished by the idea that Eleonora’s existence depended on my dreams, I would cling with innocent and delirious hope to the possibility that I was the one being dreamed of, that I was the one who only existed when Eleonora revived me in a recurring dream that visited her from time to time.

My business partner insists that it’s in our interest to purchase the harvest of a small winery in Sainte Ercienne. I’m against it. What’s more, I believe my opposition has to do with my not wanting to travel in one of those small, beat-up airplanes that are practically the only way to reach the area.

After these repeated deaths, all that remains is for a new dream to rescue us from this well of absence that are the days themselves, and then we can meet again at the roundabout in front of the Sainte Ercienne airport, so that, after patiently evoking the colors, shapes, and smells of each of the aromatic herbs, we find again that circular destiny in which each of our deaths is secretly linked to one of those innocent or malevolent plants with a different name that names it and a different perfume that envelops it.

The behavior of many couples in literature shouldn’t be freed from responsibility with regard to this habit that my dream has become. On the other hand, the compulsory death of Romeo and Juliet—to cite one such case— and their compulsory resurrection at each rereading or performance is not without mystery, a fact that not so vaguely suggests that literary works are also circular.

A shock of rust runs over the tops of the chestnut trees. Eleonora’s hair was also rust-colored, and I lightly grazed it with my hand resting on the back of her seat. The open sky above us was a very pale blue and the silence between us made the sounds of the engine, the wind, the brakes on the hilly path’s sharp curves even more present, especially the sound of the wind that, at times, suddenly snatched Eleonora’s woolen scarf and made it flutter with its wavy black and white stripes in the fresh morning air.

And once again a violent gust of wind grabs the scarf, which gets entangled in the spokes of a rear wheel, and Eleonora is dragged backwards, and the car seems to want to climb the hillside in the wake of a din of metal and glass thrown against stone, and I notice my blood is cooling on Eleonora’s face.

Because she’d come to pick me up at Sainte Ercienne’s small airport where a roundabout full of aromatic herbs with sage, rue, apple mint, thyme, rosemary, and oregano perfumed the country air of that village erected on a modest open plain between the hills.

And that’s how I ended up in Eleonora’s car after the short flight from Lyon to Sainte Ercienne, looking at the swift and tawny roofs of the chestnut trees behind her motionless, rust-colored hair, while I listed in my head the names of the aromatic herbs.

And now it’s back to waiting. Waiting for the stars to align so I can fly from Lyon to Eleonora’s hills. To arrive at the roundabout planted with ginger and mallow, broadleaved lavender and saffron. To meet once again and travel together along the undulating and serpentine road until the wind snatches away that long strip of black and white silk, and when it becomes entangled in the spokes of the rear wheel, we crash against the hillside, and my blood covers Eleonora’s face, and we die again, and I say: once again I’ll have to wait until I can return to die forever evoking the names of pennyroyal and lavender in that cool autumn morning that every now and then becomes once again the final morning.

On an ocher-colored morning of trees and golden sunshine, the six or seven passengers who had just arrived from Lyon to the small southern village of Sainte Ercienne descended from an airplane. They went their separate ways without saying goodbye, as if minutes before they hadn’t shared along with their common destination the secret terror and incomprehensible euphoria of the air.

One of the passengers walks resolutely toward a roundabout filled with small plants, where a woman is waiting for him next to a car. A long black and white scarf that the wind makes float in the air accentuates the woman’s stillness.

Now they were driving along a corniche and the wind seemed to attack the car at different points as they rounded the hill. The air was cool but it was the scarf more than the cold that signaled the changes in the wind’s direction. And when the sun shone straight on the characters’ faces (the man was me, and the woman, Eleonora) the scarf fled like a bird from around Eleonora’s neck and flew backwards. (Hazily, I remember a certain obligation regarding a winery).

Suddenly, at the top of the hill, I looked down at the golden tops of the chestnut trees that barely reached the height of the road. The scarf changed direction violently and fell like lead to the pavement. I saw Eleonora straighten and turn her face toward me with a brief, imploring glance. She let go of the steering wheel and the car seemed to pick up speed. We embraced each other almost mid-air, when we had already crashed into the hillside and the crowns of the chestnut trees were overturned and my blood stained the taut scarf caught in the back wheel of the car, and her face cooled under mine, and we were entering a place nocturnal and brilliant, forgotten by the autumn sun forever, forever.

But our death is always different, or rather, it always has a different name. It goes like this: as we drive, we list the names of the aromatic herbs in our heads. The names of other spices get mixed in with those of the aromatics: bay leaf and basil, clove and oregano. I think the roundabout also has lavender and mallow, a nutmeg and a camphor tree. Naturally, the order in which we evoke them varies. I think the crash occurs when we finish naming all of the plants in the roundabout. The last one—it always changes—pronounces our death.

My business partner is right. He’s found a buyer for the harvest before we’ve even purchased it. The offer stands until the end of the month, so on Thursday I’ll travel to Sainte Ercienne to finalize the deal.

And the man arrives with the group and separates from it. Alone, he walks toward a roundabout filled with shrubs, maybe aromatic herbs. There’s a spectator who narrates these events like in a movie. As one part of them follows what’s happening, the other enumerates: marjoram, mistol, thyme, myrtus, salvia. The man heads toward that bundle of confused aromas and between branches that are neither ginger nor mallow, nor rue nor anise, but chestnut, he spots the woman who came to wait for him. She’s standing next to a car. He notices that the wind blows unevenly, in fleeting gusts, because the scarf of heavy black and white cloth at times floats and moves away from her body, and then falls at her feet, stops, and flutters again.

The traveler approaches her and his stride is as energetic as before, but now the air seems like a translucent syrup, an invisible jelly that slows his gait as if time had had an elastic distension, and suddenly there are many more instants within the same space, so that walking a stretch has become a hardly perceptible movement.

The woman is still. Only the scarf tends to rise, float, and then fall, surely with an audible thump. And they look at each other from across a distance that barely shrinks despite the man’s steps and the anxiety of the encounter that subtly appears in the sparkle in their eyes, their secret breaths, their pulse, that no one can register but me, that as I contemplate the encounter and say the names of wormwood and myrtle, oregano and vanilla, I detect the rising flush of their cheeks and the acceleration of their pulses, and a growing heat within their breasts, and a sudden emptiness in their bellies, and a very vague and shallow trembling in their lips.

They’re face to face now, and I see, though I do not hear, that very few words pass between them, and they get in the car, which smells of leather even though its top is down under the pale blue autumn sky. She drives down a long road. I see them from the front, from behind, from the side, from above. She is attentive to the road. He, to the scarf, which has twice already freed itself violently like the tail of a comet, before returning to a quiet stillness.

Finally, and in order to relax, I realize I’m the man, the woman is Eleonora, the approaching hills over which we’ll have to climb are her native ones, the ones she has spoken to me of so many times, and then, peacefully, I once again name the spices, the aromatic herbs: broadleaved lavender, wormwood, rosemary, cinnamon, cumin, ginger . . . and mustard and myrtle? Are they there? Are they aromatic herbs? Was there thyme and verbena, pennyroyal, and anise?

Once again, the scarf flees like a terrified animal. Once again Eleonora collects it. The air is cool, but its chill is more noticeable from the scarf that moves in the wind than from its dry transparency that eagerly rummages through the roots of her hair—and travels across her skin with its crystalline smoothness. And it’s that the wind is round in the hills: here, when we ascend, we leave the sun behind us and the wind disappears. We circle the top of the hill and begin to descend, and the sun is in front of us, and with it the wind returns, searching for the black and white scarf until it overtakes it, and pulls it back, and then we start climbing again and the air calms, and I see Eleonora’s face in profile against the crowns of the chestnut trees planted on the slope, lower than the road, that have the generosity, from time to time, to frame her profile against the incredibly distant pale blue sky.

But who has died here? Me? Certainly. Or is it just a way to end the trip, and, therefore, no one has died, but no one can keep ascending and descending the hills anymore? Or is it all finished, Eleonora, me, the trip? Or do we have to list the herbs again and start all over? And yet another question: are English lavender, fringed lavender, and lavender all the same thing, do they all have the same perfume, and are they all the color of Eleonora’s eyes when autumn shines on the hills of Sainte Ercienne? And yet another question: will this not be my heaven, or my hell, and must I repeat my dream forever and forever, like a blessing or a curse?

__________________________________

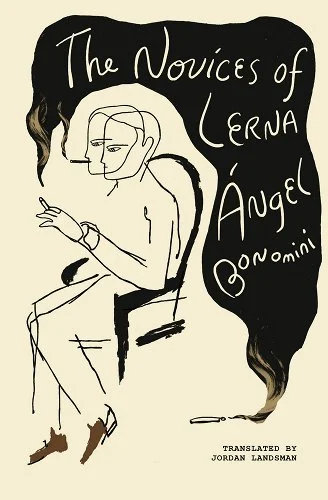

“Aromatic Herbs” taken from The Novices of Lerna by Ángel Bonomini, translated by Jordan Landsman. Reprinted with the permission of Transit Books. Copyright © 2024 by Jordan Landsman.