IOWA CITY, SEPTEMBER 2

I left my room at the Hotel Vaneau only to visit Père Lachaise. Nadia and her husband, as I later found out, hadn’t come to the airport because she had been hospitalized that day for a suspected ectopic pregnancy, and she underwent surgery the following day while I prowled the paved walks of Père Lachaise. In my search for Proust’s tomb, I arrived at Division 85, as it was marked in the map of the cemetery given to me by the guard at the gate. Skirting the columbarium, I found myself near what at first glance looked like a small Muslim cemetery, surrounded by a green hedge. Two layers of black marble, the work of Lecreux Frères, formed the tombstone of one Mahmoud Al-Hamshari, a PLO representative, who—according to the gilded French engraved on the marble—was born in the village of Em Khaled the twenty-ninth of August, 1939, and died in Paris on the ninth of January, 1973. A verse from the Koran at the head of the tombstone promised, in elevated Arabic, eternal life in the world to come to those who died for their country. Beyond the hedge, ten graves to the west, Marcel Proust lay buried. It must have been the French sense of humor that granted both of them, the man of the lost country and the man of the temps perdu, nearly identical graves: Lerendu Cie. had bestowed upon Proust, about fifty years before the death of Al-Hamshari, two simple layers of shining black marble. Fifty years separate the two lost times, the two darknesses. But both are equally lost under the flowers of remembrance.

I stood there by the green hedge and thought about Yehoshua Bar-On, whom I had called from a café not far from the main gate of the cemetery. I had apparently disturbed his Schlafstunde. I thought about Shlomith, and about the two of us, as possible protagonists in a story by Bar-On. Two lost characters whose fate, on paper and otherwise, is in his hands, at the mercy of his whims. But he will never put himself at my mercy, because he is off limits for me, beyond the limits of my life and my writing. A restricted zone of sorts. Then I imagined a parting from Shlomith, and I said to myself, Well, everything has come to the end that was destined by its beginning, and nothing but a squeezed honeycomb separates the beginning from the end. And under the black marble lay the two lost men, each in the darkness of his own tomb, a Jew of Time and an Arab of Place. And apart from the almost matched graves and the avenue of trees reflected in the smoothness of the black marble, they appeared to share nothing at all.

The next day, on the way to the airport, I picked up Bar-On at Des Écoles, and we shared the cost of the taxi. Last night, he told me, he had come to the conclusion that he just couldn’t cope with being all by himself for several months in a strange environment, or deal with new people, new loneliness. He likes to write surrounded by his books, sitting at his antique desk, by the light of the antique lamp he had bought, together with the desk, in the flea market in Jaffa, and with his favorite paintings on the four walls. At teatime his wife sinks into the armchair on the other side of the desk and listens to what he wrote the night before. As I gazed out the window at the streets of Paris flooded with light, a dubious envy washed over me. Later, on the plane to Chicago, he confided to me the real reason that, despite it all, he was traveling to a godforsaken town in the Mid-west.

“I’m writing a new novel. With an educated Arab as its hero,” he told me. “I don’t think I’ll ever have this kind of opportunity again—to be under the same roof with a person like that in ideal conditions of isolation.”

I regarded him with astonishment and said, “We have one little problem. I don’t think of myself as what you people call ’an educated Arab.’ I’m just another ’intellectual,’ as you call your educated Jews.”

He laughed and puffed at his extinguished pipe.

“In addition to which,” I said, “I hope you won’t be breathing down my neck the whole four months.”

He immediately began to apologize that he hadn’t expressed himself properly. “All I want is to get to know you from up close,” he said, “while at the same time preserving a certain amount of aesthetic distance between us, for the sake of objectivity, you know.”

“I shall try my best not to disappoint you.”

Then he fell asleep.

I thought, Maybe before he wakes up I’ll prepare an imaginary autobiography for him, a tale convincing enough to shield me from his critical eye. And when he opened his eyes and asked me why I was looking depressed, although in truth I was in high spirits, I said maybe I would let him use some of my yarn to spin his tale.

I fabricated for him a parting from Shlomith, upon which I embroidered several heartrending details. He whipped out his notebook and began to chronicle my love for the redheaded wife of an army officer, who was in the throes of a legal battle with him over the fate of their son. And as the story grew longer and more intricate, I became more and more aware of the delights of dissembling, the joy granted those who take the liberty to enchant with their imaginary lives. And Bar-On, pleased with the clear understanding we had reached of our respective roles, said he hoped we would enjoy this experience equally. While all this was going on, I was thinking about Proust and Al-Hamshari, and about how livid the man sitting next to me would be if he knew what odd twinnings and pairings were running through my mind.

As for me, I doubt that I would have gotten to Iowa City were it not for Willa Cather’s My Ántonia, the first novel I ever read, which I found in our olive-green bookcase, embedded in the thick wall. This was a hefty volume, in a soft turquoise cover, decorated with a black-and-white drawing of a boy and a girl, their backs to the reader, facing what was supposed to be an endless ocean of red grass on the prairies of Nebraska. It was in an Arabic translation, whose opening I used to know by heart:

Last summer in a season of intense heat, Jim Burden and I happened to be crossing Iowa on the same train. He and I are old friends, we grew up together in the same Nebraska town, and we had a great deal to say to each other. While the train flashed through never-ending miles of ripe wheat, by country towns and bright-flowered pastures and oak groves wilting in the sun . . . During that burning day when we were crossing Iowa, our talk kept returning to a central figure, a Bohemian girl whom we had both known long ago. More than any other person we remembered, this girl seemed to mean to us the country, the conditions, the whole adventure of our childhood. . . . “From time to time I’ve been writing down what I remember about Ántonia,” he told me. . . . When I told him that I would like to read his account of her he said I should certainly see it—if it were ever finished.

Months afterward, Jim called at my apartment one stormy winter afternoon, carrying a legal portfolio. He brought it into the sitting room with him and said, as he stood warming his hands, “Here is the thing about Ántonia. . . . I suppose it hasn’t any form. It hasn’t any title, either.” He went into the next room, sat down at my desk and wrote across the face of the portfolio the word “Ántonia.” He frowned at this a moment, then prefixed another word, making it “My Ántonia.” That seemed to satisfy him.

In Chicago we were wait-listed for the flight to Cedar Rapids, north of Iowa City. We sank into two red plastic seats, the ones closest to the reservation desk. Bar-On was alert and full of vitality after his good sleep on the plane, and he delved into his notebook, while I, my times jumbled, sank into a twilight slumber, to the extent the hard seat permitted. Half asleep, I heard the tapping of heels coming closer, and as one man we whipped around to gaze in her direction, he from his notebook and I from my slumber. Bar-On leaned toward her, clutching his knees, his eyes glistening with enthusiasm. “Let’s hope that she’s also going to the International Writing Program,” he said.

There was about her something distant and inaccessible, something that tautened her body like a bow between the torrent of her hair and the tapping of her heels. And the profusion of her body, trapped in a gossamer blouse and a severe skirt, threatened to burst forth at every tap of her heels and flood the terminal. Bar-On began to recite: “‘I placed a jar in Tennessee/And round it was, upon a hill./It made the slovenly wilderness/Surround that hill.

“‘The wilderness rose up to it—’ But clearly we’re talking about two jars here.”

“But only one wilderness,” I said, meaning him. He smiled forgivingly, pocketed his notebook and took out his pipe. I sank back into slumber.

In the plane it so happened that I sat next to her, and Bar-On sat two sighs away, across the aisle. As the plane took off, her mouth opened as if she wanted to say something but changed her mind and went on sitting there with her mouth ajar. The stewardess approached her and said, “Is there anything I can do for you?”

__________________________________

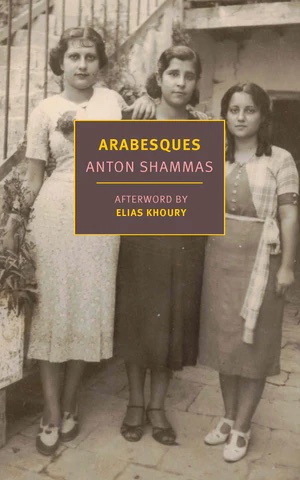

From ARABESQUES by Anton Shammas, translated from the Hebrew by Vivian Eden. Used with permission of the publisher, NYRB Classics. Copyright © 2023 by Anton Shammas/Vivian Eden.