The Scent of Paradise

“It has been like this from the beginning. Even as a child, you were sick all the time. First it was the intestines, yes, intestines… Yours are fragile, there were things you couldn’t eat. I fed you only milk and your belly never deflated. I hoped from the bottom of my heart that, thanks to my milk, someday you would be as white as a Fassi, not brown like us. But you quickly turned yellow, even your eyes were yellow. I was afraid for you, afraid of jaundice, which had taken so many people from our village to the other world, the green world. It wasn’t jaundice. You stayed yellow. They called you Yellow Abdellah.”

“And then, once you began to leave the house, to run barefoot though I told you not to, to play soccer with Zeneib’s sons, the sun was unkind to you. It didn’t like your yellow hue—perhaps it saw you as competition. No, it never treated you kindly. It regularly attacked you. You’d fall. For five or six days, you wouldn’t be able to lift your head. It gave you a horrible fever, a mad fever, the same fever that made El-Maâti into a majdoub, aimlessly wandering the streets. But he’s apparently mabrouk: Hadda finally got pregnant simply because, for a month and three days, she fed him lunch. I couldn’t imagine you as a majdoub. Unable to pronounce the words, I silently prayed for another fate, I almost wanted to create it. The fever lasted, without any sign of letting up. It was as if a bad djinn was living in you, a djinn you’d trampled underfoot without wanting to, injured unknowingly. It was taking its revenge on you, it became the sun’s accomplice.”

“Medicine would revive you. Medicine is expensive. But I had my own ways of curing you. It was my stepmother, the woman who replaced my mother in my father’s bed and whose name I never wish to speak, who passed them on to me. Ways to cool a burning body, to drive off evil spirits, to control a man, to cast off spells, to smell the scent of paradise.”

No, the sun had never been kind to me, it often punished me and deprived me of my health. Fever, fever. I saw another world, laying in my bed, dripping with sweat, my mother at my bedside. A world ruled the succubus Aisha Qandisha, who’d terrorized me as a child, queen of the shadows. I hurled so many insults at her, on her head, her breasts, her monstrous sex. I bothered her so many times as she did her laundry underground. She knew that she’d have a chance to get her revenge, torture me, beat me, call upon her invisible husband’s secret army to use my body for target practice and besiege my brain with the worst of nightmares. Even as an adult, when I was in my twenties, she’d manage to return me to my childhood and its fears. Once more, the world would spin wildly around me, once more I’d scream without being heard, once more I’d spill hot tears that burned me but flowed within. I lived in hell, roasting as my aunt Massaouda called it.

Luckily, my mother was gifted and could show me heaven, make me smell it, briefly.

“I used to go into the woods and look for the crying trees, trees that bend down, that give of themselves willingly, that allow themselves to be picked. Eucalyptus. I’d take a few branches with leaves that were still fresh, bright green in color, not dark green. I’d gather them from seven trees. I didn’t deface these trees. I asked them as I picked, I asked permission: above all, you mustn’t hurt them, ever. Guard their friendship, we’ll always need them.”

“After that, I’d visit the herbalist to buy henna, orange blossom water, as well as a few amulets to ward off the evil eye and undo the fasoukh’s pestilence. I would never forget the jaoui, which gives off, when burned, a scent for which angels have a particular fondness.”

“When I returned to the house, I’d crush the eucalyptus in the mortar, I’d add henna and in the end, I’d flood the mixture with orange blossom water. In this way, I created a scent that brought the spirit back to the body, a scent that opens the eyes and wards off all bad things. This is the blessed scent of paradise.”

“Once the preparation was finished, I’d wrap your head in a blue scarf in which I’d put my sacred mixture. And I’d leave you alone like that, alone with God. Your face would quickly turn green, your pores would open up, and the battle would begin. I’d turn off the light and leave.”

A cool, cool wind would fill my body, accompanied by a scent that matched coolness, an herbal scent, a scent that settled in to my body little by little. I knew this scent. It awoke my worries, my fears, it freed me and frightened me at the same time… I slept and didn’t sleep. I remained very aware of the battle being fought between spirits in my body. The bad ones were strong, they wouldn’t leave easily, they used all their power to raise my temperature, they shattered me, they spit on me. They filled me with horrifying images, blood everywhere, a knife that stabbed my heart and the feeling that I no longer existed, that I was done, that I believed myself lost, destined for God’s hell. Still, I knew that the Prophet Mohammed—peace be with him—would save me. I was afraid. I was alone. I prayed mechanically, recited all the suras of the Koran I’d been taught at the msid. I resisted. I fought weakly.

This hell, this torture lasted an eternity. I watched the years pass, observed all the work of it, unable to speed up the process. It was an eternity that saw me constantly laid out in my bed, suffering, broken. Between life and death.

But soon, an ocean breeze would enter from the north, from above. Soon it would envelop me entirely and chase the disciples of Iblis back into the darkness. For it was Iblis, the most beautiful of angels, who led the attack. He was invisible, but I could feel his presence, his influence. The ocean breeze continued to free me, to support me. Iblis eventually drew back, followed by all those who worked for him: his wife, Aisha Qandisha and the bad djinns.

My fever would finally break. I was saved. At that moment, enormous doors like the ones in the Rabat medina would open before my eyes. Gardens everywhere. And above all, the scent of these gardens, the scent of paradise. I didn’t recognize anything, everything was green, everything was new. Only the henna and eucalyptus were familiar to me. There were happy people, not many, people of a type that don’t exist on earth. A magnificently handsome naked guard named Rayan. He asked me: “Do you observe Ramadan as you should, following all the rules?” I was preparing to answer, to lie. He added: “Don’t lie, I’ll know it.” He inspired confidence in me: “I’m young, I’m only sixteen, I can’t fast until the end, I’m not strong.” So he recommended: “If you wish to be among the happy people you see playing and tasting joy someday, you must respect Ramadan. I’m the one who guides good fasters to heaven.” And I’d wake up. It was morning. My M’Barka had made semolina porridge. She looked at me, touched me, then opened the window and thanked God. Birds sang. I’d then tell her about my dream. She’d listen to me religiously. She understood me.

Oussama

Whenever Oussama went to the hamam, it still showed two days later. His pale skin was still red and I was green with envy. His family wasn’t from Fes or Rabat, and yet there was something distinguished about him, like a rich boy who wanted for nothing. And he was smart too. The proof: he wore glasses.

Oussama had everything I didn’t. A stable family—the father, highly intellectual, a military judge; the mother, a cultured house- wife and excellent cook, a refined woman anyone would want as a mother; two brothers and only one sister. They didn’t have money problems. They seemed peaceful, happy.

Yes, I liked Oussama’s family. How often I’d wish I could take his place, or at least be his brother and share his luck. I liked that family and I couldn’t help hating them. My heart was in constant conflict, love and hate engaged in a ruthless war.

I met Oussama during our first year of middle school. Love at first sight. I was drawn to him and stared at him often, for long stretches of time, my mind full of questions. I could sense that he was smart, superior. His cheeks, which were always red, drove me crazy. I adored them. They made him look like a little Christian.

During that first year, he proved to be even smarter than I’d assumed. He was first in our class in every subject. He had it all. It would be ridiculous to say there was any competition between us. He was way ahead of me and I was no dunce. I did well on my exams, but not like Oussama. He didn’t seem to do anything in particular, and yet he finished first in our class each term, almost effortlessly. There was no suspense: we knew from the beginning how it would turn out. I really admired him; I think I even idolized him. I wanted to spend my time with nobody but him, hoping that his baraka, his blessing, would rub off on me at least a tiny bit.

I never left his side—sat next to him in every class, followed him around during recess. I’d pick him up before school: “It’s on the way. I don’t mind.” I left my house an hour early to be sure I could stay at his for at least fifteen minutes, spend fifteen minutes in his company, intensely. Breathing the air in his house, its distinct and delightful scent. It also gave me time to compare his home with mine. Of course, I didn’t like anything about ours. Oussama’s house, now that was more my style. I would have loved to live there and never leave, spend all my days in that house full of books, where everything was organized, where everything seemed magical. It was the house of my dreams. I was in a trance. I’d stop by every chance I got. I really must have bothered him, disturbed him though I didn’t mean to. I took it too far, past the limits of friendship.

His mother liked me, I think. His father would say hello from time to time. Their intimacy fascinated me. I even took an interest in the walls that sheltered them. I touched them to examine them, to uncover their secrets.

Oussama had a young aunt on his mother’s side who was in her twenties and very beautiful. A small brunette with magnificently black eyes, thin lips that were constantly smiling. She seemed like the ideal woman for my older brother, who was looking for a wife at the time. If I only had the power to join our two families, combine them, mix our blood, I would happily have done so. I spoke to Oussama about it and he responded, amused, “Stop dreaming, she’s already engaged. She’s getting married in a year.” Cruel Oussama! She had a fantastic name: Badiaa. Badiaa, the woman my brother would never marry. Is she happy in her marriage now, still as beautiful and fresh as always?

In the first year of middle school, there was one biology teacher whom I deeply hated. She taught well enough. But she only had eyes for Oussama. She doted on him shamelessly in front of all the other students. She’d even caress his pink cheeks, to congratulate him on his good work supposedly. But it was obvious: that dry, bony old maid—that’s what we called her—fantasized about little Oussama. And since she had authority over him, she took advantage of it. She had no right to do that. All the other students noticed this special treatment and took every chance they got to make fun of poor Oussama about it, to tease him mercilessly. He would blush deeper and deeper, to my great pleasure. Luckily, this teacher switched schools the following year. I don’t even remember her name.

Over the next three years my passion for Oussama remained as intense as ever. But with time I learned to hide it, to keep my distance, suffer alone in silence. I learned to give him space. What’s more, as I began gravitating toward literature, he moved toward the sciences. We separated. With age, you learn how to lie to yourself, to become reasonable: you reflect more, become less spontaneous. But, at least, thanks to this introspection, you get to know yourself better.

As for Oussama, I lost track of him for eight years. Three years ago, I found him again. And it all came back to me

__________________________________

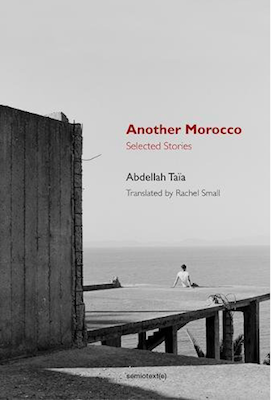

From Another Morocco: Selected Stories. Used with permission of Semiotext(e). Copyright © 2017 by Abdellah Taïa translated by Rachael Small.