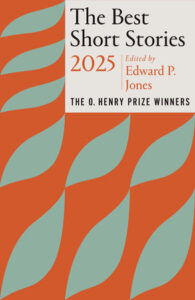

Announcing the Winners of the 2025 O. Henry Prize for Short Fiction

Series Editor Jenny Minton Quigley on the Timeless Power of Channeling Truth Through Imagination

Last summer, as our guest editor was reading through a hefty box of stories to select his 2025 O. Henry Prize winners, The New York Times announced their list of the one hundred best books of the twenty-first century. Can you guess whose work was included among the best works of fiction by American writers in the 2000s? Of course, the answer is our guest editor Edward P. Jones, who appears on the list twice: first with his Pulitzer Prize-winning novel, The Known World (2003), listed at number 4, and again with his story collection All Aunt Hagar’s Children (2006) at number 70.

To highlight his prestigious showing on the list, renowned New York Times critic A. O. Scott traveled to Washington, DC, for an interview with Jones. A quarter of the way into our current century, a writer like Jones, who is not on social media or regularly out promoting himself, might seem to occupy a more distant place in the literary firmament than showier and more recently arisen stars. The headline of Scott’s piece is “Visiting an Elusive Writer and Revisiting His Masterpiece.”

A historical novel, The Known World revolves around a Black slave owner in nineteenth-century Virginia, and Scott assumed it had been heavily researched. But while listening to Jones, Scott suddenly understood: “My mistake had been assuming that the novel, which feels absolutely true on every page, was in some way an empirical achievement, rather than a triumph of imagination. Repeatedly in our conversation, Jones asserted the fiction-writer’s freedom—his delight and also his duty—to make things up.”

Marveling at the ways writers make things up is on Edward P. Jones’s mind these days. Throughout this delightful year spent observing him at work selecting the 2025 O. Henry Prize winners, it’s been clear to me that his objective is to find the kinds of truth that only that “fiction-writer’s freedom” to invent, shape, communicate, and testify can yield. The stories he’s chosen are indeed triumphs of imagination that ring truer in our hearts and minds than any thin facsimiles of reality we’ve come to accept as substitutes for the real thing in an age saturated with cheap information.

What lies in the pages ahead are not brilliant writers showing off what they know or what they have overheard, but true stories they have dreamed up out of nothing.

Jones has won two O. Henry Prizes for stories published in The New Yorker and included in All Aunt Hagar’s Children. Small miracles of the imagination appear throughout his collection. Describing Jones’s writing won’t do it justice, so I will include just a few examples. From the opening story, “In the Blink of God’s Eye”: “They stood there for a long time, time enough for the moon to hop from one tree across the road to another. The moon shone silver through all the trees…most generous with the silver where it fell, and even the places where it had not shone had a grayness pleasant and almost anticipatory, as if the moon were saying, I’ll be over to you as soon as I can.” Really you can open to any page. From “Old Boys, Old Girls”: “He was not insane, but he was three doors from it, which was how an old girlfriend, Yvonne Miller, would now and again playfully refer to his behavior.” Even out of context, these lines soar, and what they do in context—well, you can imagine.

Reading Edward P. Jones while corresponding with him this year has been a thrill. He has a modest, strong voice and an observant, accepting sense of humor. When I wrote to him about “In the Blink of God’s Eye,” he responded, “Once I knew the story I wanted to tell, it became somewhat fun. I didn’t know anyone who was in DC in 1901, so I just had to go with what I knew the country had at that time—like little gas lights at the end of corners and people relying on horses for travel. And at the center I could see in my mind that this young woman loved that guy and was happy to go across the Potomac to a foreign country to be with him. The phrase ‘You can’t make that stuff up’ is simply not true.” Jones is an illuminator. To use his own phrase, he is “generous with the silver.” When we notified the winners, it was remarkable how many said they were inspired by his writing.

Separated by a century, Edward P. Jones and O. Henry share a desire to expose the truth by turning phoniness inside out and shaking out its contents. In O. Henry’s story “One Dollar’s Worth,” a counterfeit coin made of lead is used to save the day. In “Old Boys, Old Girls,” Jones conjures new life from old relics. “The girl had once seen her aunt juggle six coins….It had been quite a show. The aunt had shown the six pieces to the girl—they had been old and heavy one-dollar silver coins, huge monster things, which nobody made anymore.”

Are we making real magic anymore? Last summer was also when I discovered artificial intelligence in service of celebratory toast-making. A grandson gave a sweet tribute to his grandmother at her birthday party. Later his mother told me that ChatGPT wrote it. The next month several of us plugged details about a friend into ChatGPT to churn out a sentimental toast for her wedding. The program strings together coined phrases like “in hindsight,” “in all seriousness,” and “May your love continue to shine brightly” to sweeten its sauce. But it’s full of clichés and as light as confetti. It can’t be true. Perhaps the future of creative writing is what AI cannot overhear, as it has yet to be spoken. In the “Writers on their Work” section at the back of this book, so many of this year’s winners describe their imaginations at play in the writing process, in ways that no chatbot could imitate.

What lies in the pages ahead are not brilliant writers showing off what they know or what they have overheard, but true stories they have dreamed up out of nothing and turned into weighty silver dollars, coins that shine under Jones’s moon as it hops from story to story, “as if the moon were saying, I’ll be over to you as soon as I can.”

–Jenny Minton Quigley

*

“The Stackpole Legend”

Wendell Berry, The Threepenny Review

“The Arrow”

Gina Chung, One Story

“That Girl”

Addie Citchens, The New Yorker

“The Pleasure of a Working Life”

Michael Deagler, Harper’s Magazine

“Blackbirds”

Lindsey Drager, Colorado Review

“Hearing Aids”

Clyde Edgerton, Oxford American

“Sanrevelle”

Dave Eggers, The Georgia Review

“Stump of the World”

Madeline ffitch, The Paris Review

“Shotgun Calypso”

Indya Finch, A Public Space

“City Girl”

Alice Hoffman, Harvard Review

“Sickled”

Jane Kalu, American Short Fiction

“The Spit of Him”

Thomas Korsgaard, translated from the Danish by Martin Aitken, The New Yorker

“Winner”

Ling Ma, The Yale Review

“Countdown”

Anthony Marra, Zoetrope

“Just Another Family”

Lori Ostlund, New England Review

“Mornings at the Ministry”

Ehsaneh Sadr, Ploughshares

“Rosaura at Dawn”

Daniel Saldaña París, translated from the Spanish by Christina MacSweeney, The Yale Review

“Three Niles”

Zak Salih, The Kenyon Review

“Strange Fruit”

Yah Yah Scholfield, Southern Humanities Review

“Miracle in Lagos Traffic”

Chika Unigwe, Michigan Quarterly Review

__________________________________

Excerpted from The Best Short Stories 2025: The O. Henry Prize Winners, edited and with an introduction by Edward P. Jones; Jenny Minton Quigley, Series Editor. Copyright © 2025 by Vintage Publishing, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved.

Jenny Minton Quigley

Jenny Minton Quigley is a writer and editor. She is the series editor for The Best Short Stories of The Year: The O. Henry Prize Winners, and the author of a memoir, The Early Birds. She is the daughter of Walter J. Minton, the storied former president and publisher of G. P. Putnam's Sons, who first dared to publish Lolita by Vladimir Nabokov in the United States in 1958. A former book editor at several Random House imprints, Minton Quigley lives in West Hartford, Connecticut, with her husband, sons, and dogs.