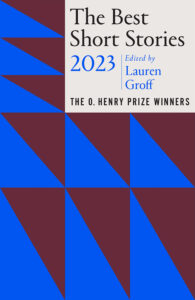

Announcing the Winners of the 2023 O. Henry Prize for Short Fiction

Lauren Groff on This Year's Winners and the "Infinitely Malleable, Gorgeously Economical, and Endlessly Surprising" Short Story Form

If heaven exists, it must exist in the form of a clean and quiet house, a comfortable chair near a snoring dog, a glass of cold wine, and a lapful of short stories. I love the short story form with a wild-eyed passion, the fervor of a street-corner evangelist who dresses up in robes to shout at pedestrians about angels and harlots and the seven-headed beast of the end of days.

But short stories are, to me, closer to the dawn of days; they are quick, breathtaking windows into other humans’ souls, which is where the infinite resides, in my personal credo. The story form is infinitely malleable, gorgeously economical, and endlessly surprising; it is long enough to lose oneself in, short enough to deliver a satisfying gut punch. I say this to contextualize why, when O. Henry Prize series editor Jenny Minton Quigley asked me to be this year’s guest judge, I must have terrified her by responding in enthusiastic all-caps within thirty seconds of her invitation.

It has been a delight to revel in short stories the past several months, to read hundreds upon hundreds, written by people from all over the world, with so many exquisite voices and so many idiosyncratic understandings of what a short story is and what the form can be stretched to do. I could have selected five times as many great stories and made five equally marvelous books; alas, I could only choose twenty stories for this year’s anthology.

But, oh, what brilliant stories these are. I know it is the custom for the writers of such introductions to shout out each contribution by name with a compliment, perhaps a way of justifying for a large audience choices that are so deeply individual and subjective. I wonder, however, if this practice risks minimizing or simplifying the appeal of deeply complex stories like those that are found in this anthology, each of which is excellent in multiple, and sometimes even contradictory, ways.

Instead, I’ll say that each of these stories had to pass a few rigorous tests, the first and most important of which was that they had to show some sort of thrill or risk in terms of language or structure or plot or enigma; something in the story had to deliver a sharp blue jolt of electricity to my nervous system.

The second test was that each of the stories had to subvert my expectations, and some succeeded to the point where they made it past my deepest, most ingrained antipathies. For example, halfway through the year, I asked Jenny to please stop sending me any more first-person stories because, while there were so many perfectly competent ones coming to me, I began to resent being anchored again and again to individual consciousnesses; I began to feel at the center of a sucking collective whirlpool of anxious solipsism.

It’s true that ours is a largely secular time, and some of us are urged to self-help, self-care, self-seek; far too many others among us subscribe to a sort of cranky and (to me) unbearably myopic libertarianism. All of this, mixed together, leads to a culture of somewhat hypertrophied individualism, a large-scale cult of the singular self. Perhaps because of this, the godlike third person, peering down at the story’s characters from its distant hover, like an enormous all-seeing hawk, can feel uncomfortable to contemporary writers. Jenny did mostly stop sending me first-person stories, but some eventually broke through to the final anthology because the writer was doing something new, or the story throbbed with vitality, or made me see the familiar world as warped or strange.

In addition, I used to have a screaming aversion to stories in the second person, but—welp!—not anymore, because of a single brilliant example in this anthology that smashed the aforementioned dislike to smithereens. An excellent story can, indeed, break open irrational hatreds. This is one of the great gifts of narrative. This is also why so many of us need to fling our phones into a bog and start reading literature again.

The story form is infinitely malleable, gorgeously economical, and endlessly surprising.

The final test for each story was that I had to remember it weeks and months after I first read it. This was harder than it sounds; halfway through reading for this anthology, I contracted COVID-19, and I was in such a state of brain fog for so long afterward that I genuinely feared I’d never be able to write a sentence again. Brain fog also made reading far harder; every time I sat or lay down to read, I’d fall asleep within an instant.

So I began to read while marching around the house, driving my dog and children bonkers, and after some time, I grew to love this form of moving meditation. I knew a story was good if I started stepping to its rhythms. I kept finding smart stories to throw into the enthusiastic maybe! pile. This stack grew until it was taller than my dog, which is saying something, as she’s a leggy labradoodle whose snout rests comfortably on my hip when I am standing still.

With this final test, there was a sort of natural winnowing that happened; some stories I found excellent on first reading, but then I couldn’t remember them. It may have been my brain fog, or it may have been because our aesthetic sense is fickle and often dependent on things outside our consideration when we encounter art; perhaps we had insomnia the night before, or the coffee from our favorite café was cold and bitter, or someone was nasty to us on the internet and it threw off our taste for the piece at hand.

Which is to say that the stories in the towering maybe! pile were likely deserving of being in this collection, but also that art finds us at the time that we need it, or when we can be open to it, at moments when we are vibrating at the frequency that the art is putting into the world. The self is unstable and shifts so radically through our days and years that it’s unrealistic to presume we’d respond the same way to any piece of art every time we encounter it.

Mostly, in the end, I was building the collection slowly, story by story, balancing one story against another, trying to get a feel for the whole collection. While I do love the individual short story with a proselytizing fervor, if it’s possible I love the well-thought-through collection of short stories even more. The best collections have an invisible architecture to them, in which the first story asks a question or makes an argument, and this initial question or argument is then fractured and complicated by the next story, and so on, story by story, until the glorious grand finale that, upon ending, sends a sort of prismatic light shooting back into daily life.

I was trained early in this kind of aesthetic construction; it was probably my first serious artistic love. I was a child of the eighties, an adolescent in the early nineties, and I owned first a beige Fisher-Price tape recorder, then a giant black boom box, and out of these I made mixtapes assembled with extreme thought and care, the covers decorated with magazine collages and Wite-Out and nail polish, my most legible block handwriting listing the songs on the insides.

This was before music could be found with a few strokes of a keyboard; to claim a song heard on the radio, we had to sit for hours with our finger on the record button, just hoping that when the song we longed for would finally play we’d recognize it by its opening bar. To assemble a mixtape, we put careful thought into the pace of the songs, the speed, the key they were in, the kind of beat they bore, the quality of the singers’ voices, the genre of the music, the way that the energy moved from song to song, the emotional place where all the songs, together, ended up. Mostly we thought about the person we were making the mixtape for: what we knew they already liked, what we thought they might like, what we wanted them to feel when listening to this beautiful thing, this gift of art, that we’d made for them.

The Best Short Stories 2023 was assembled for you, dear reader, to give you a sense of the enormous range and capacity of the contemporary short story, to make you laugh, to bewilder and delight and scare you, to show you the thriving ecosystem of the short story as it existed in the world this strange third pandemic year, to give you a glimpse of the extraordinary diversity of voice and journal and nationality and subject matter that the short story, most vibrant of narrative forms, encompasses.

You will certainly like some of these stories more than others; some will be set at your current vibration levels; it seems likely to me that others that you may not appreciate just now will find you where you will be at some point in the future. If our adolescent mixtapes were a shy declaration of affection, please accept this year’s O. Henry anthology for what it is: a loud declaration of love.

–Lauren Groff, editor for The Best Short Stories of The Year: The O. Henry Prize Winners

*

Ling Ma

“Office Hours,” The Atlantic

Catherine Lacey

“Man Mountain,” Astra

Jonas Eika

“Me, Rory and Aurora,” translated from the Danish by Sherilyn Nicolette Hellberg, Granta

Gabriel Smith

“The Complete,” The Drift

Jamil Jan Kochai

“The Haunting of Hajji Hotak,” The New Yorker

Lisa Taddeo

“Wisconsin,” The Sewanee Review

Rachel B. Glaser

“Ira & the Whale,” The Paris Review

Naomi Shuyama-Gómez

“The Commander’s Teeth,” Michigan Quarterly Review

Rodrigo Blanco Calderón

“The Mad People of Paris,” translated from the Spanish by Thomas Bunstead, Southwest Review

Shelby Kinney-Lang

“Snake & Submarine,” Zyzzyva

Jacob M’hango

“The Mother,” Short Story Day Africa

’Pemi Aguda

“The Hollow,” Zoetrope

Cristina Rivera Garza

“Dream Man,” translated from the Spanish by Francisca González-Arias, Freeman’s

Grey Wolfe LaJoie

“The Locksmith,” The Threepenny Review

Kirstin Valdez Quade

“After Hours at the Acacia Park Pool,” American Short Fiction

Arinze Ifeakandu

“Happy Is a Doing Word,” Kenyon Review

David Ryan

“Elision,” New England Review

K-Ming Chang

“Xífù,” Electric Literature

Kathleen Alcott

“Temporary Housing,” Harper’s Magazine

Eamon McGuinness

“The Blackhills,” The Stinging Fly

__________________________________

The Best Short Stories 2023: The O. Henry Prize Winners, edited by Lauren Groff; series edited by Jenny Minton Quigley, will be published in September by Anchor Books.

Lauren Groff

Lauren Groff is a three-time National Book Award finalist and The New York Times–bestselling author of the novels The Monsters of Templeton, Arcadia, Fates and Furies, and Matrix, and the celebrated story collections Delicate Edible Birds and Florida. She has won The Story Prize, the PEN/O.Henry Award, and been a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award. Her work regularly appears in The New Yorker, The Atlantic, and elsewhere, and she was named one of Granta’s 2017 Best Young American Novelists.