Annihilation, Beauty, and Shakespeare: Is Juliet the Best Dead Girl?

Sophie Duncan on the Morbid Entertainments of Sex and Death

When Romeo sees his wife’s corpse in the tomb, his first thought is how sexy she is. He’s just murdered a man, and is surrounded by other corpses, including his wife’s cousin, whom he also killed. Nonetheless, nothing detracts from the luminous sexiness of Juliet, his dead 13-year-old bride.

He describes this allure in the language of erotic jealousy: a piece of paranoid Renaissance rhetoric, in which he professes to “believe / That unsubstantial death is amorous,” and the “lean abhorred monster” has imprisoned Juliet “here in dark to be his paramour” (5.3.102–5). Her asphyxiation becomes Death’s kiss, as he has ‘sucked the honey of [her] breath’ (5.3.92).

Romeo is hardly the first character to link sex, death and Juliet in the play. On discovering Juliet apparently dead in her bed, her own father swiftly imagines that Death has been in the night and had sex with his child: “Flower as she was, deflowered by him.” The two most important men in Juliet’s life both look at her corpse and see an intensely sexual object.

She is a “fair corpse,” to be shown off publicly “in all her best array” (4.4.108–9); she is, to Romeo, a spectacular beauty who makes her tomb “full of light” (5.3.86). There are four corpses and at least 12 other people onstage by the time the play ends, but Juliet’s dead body remains the spectacular centerpiece of the now very crowded tomb.

The dead girl has always been attractive entertainment. In the earliest surviving description of a performance of Othello, from 1610, Oxonian clergyman Henry Jackson describes “famous Desdemona killed before us by her husband,” noting that “although she always acted her whole part supremely well, … when she was killed she was even more moving, for when she fell back upon the bed she implored the pity of the spectators by her very face.”

The heart-rending expression of a boy-player’s female corpse begins a tradition still prevalent in Shakespearean performance: a Shakespeare heroine smothered in her bed does not look like a bruised, violated victim disfigured by petechiae, bleeding lips and burst blood vessels, but like an attractive young woman lying with her eyes shut.

When a girl is dead, she can be loved as never before.[/Shakespeare was not alone in his celebration of the female corpse. In Thomas Heywood’s domestic tragedy A Woman Killed With Kindness (1603–7), the adulterous wife Anne Frankford demonstrates her remorse by starving herself to death. In doing so, she not only conveniently writes herself out of the narrative—clearing the way for her husband’s remarriage—but, through her self-starvation, erases and desexualizes her rebellious body.

Middleton took his obsession further in The Second Maiden’s Tragedy (1611), where the heroine’s onstage corpse becomes the villain’s necrophiliac loveobject, painted to look more alive. In the eighteenth century, the new novel form saw heroines die their way out of sexual subjection, or be gorily murdered in early Gothic novels.

A threnody of dead girls in nineteenth- and twentieth-century fiction swiftly writes itself: Little Nell to Beth March, Juliet to JonBenét. Highbrow Scandi noir and the most derided slasher flicks rely equally on serial killers with a penchant for nubile blondes—from those murdered before the opening credits to the manacled survivor who screams in her underwear while the hero races against time.

Inside Catholic churches, martyred virgins offer us their ecstasy, while troubled celebrities become angels once they overdose. Writers before and after Edgar Allan Poe have agreed that “the death, then, of a beautiful woman is, unquestionably, the most poetical topic in the world.”

We garb ourselves in dead girls—or at least, in their garments. High-fashion brands routinely pose models as corpses to sell designer clothes and accessories—a 2006 Jimmy Choo ad staged Molly Simms dead in a car boot, with Quincy Jones-as-murderer brandishing a spade.

In 2014, Marc Jacobs posed singer Miley Cyrus beside an apparently drowned model on a moonlit beach.3 Photographer Izima Kaoru’s 1995–2008 series Landscape with a Corpse varies the theme by basing the images on each model’s “fantasy of a perfect death,” including “which designer clothing they imagine wearing when people discover their dead body.”

This may unsettle you, as it unsettled me—why should fashion models have ready-made fantasies of a “perfect death”? But patriarchal society forces women to prepare for, imagine, and simultaneously obsessively avoid our own deaths. This begins in adolescence, when girls are necessarily taught that some men (and it is overwhelmingly men) are murderous predators from whom they are always at risk.

Society instructs girls that it is their responsibility to cheat death by not walking or dressing or existing in certain times, manners and locales. Rebecca Solnit takes it furthest: “To be a young woman is to face your own annihilation in innumerable ways or to flee it or the knowledge of it, or all these things at once.”

Adolescent dead girls are frequently depicted as culpable, hapless, reckless. In fiction, as Alice Bolin notes, they are “wild, vulnerable creatures” whose bodies are both “a wellspring of, and a target for sexual wickedness.” Girls are taught by society to fear the danger in the darkness, while society secretly believes that the danger was in girlhood all along.

Hollywood has, for Bolin, a “necrophiliac quality,” and the young Rebecca Solnit gave away her television after a night in San Francisco when “a young blonde woman was being murdered on each channel.”

Nonetheless, the lust for the beautiful bodies of dead young white women is much older than America. When a girl is dead, she can be loved as never before.

__________________________________

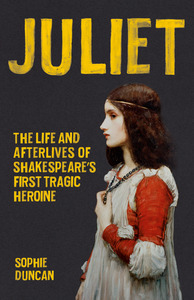

Excerpted from Juliet: The Life and Afterlives of Shakespeare’s First Tragic Heroine by Juliet Duncan. Copyright © 2023. Available from Seal Press, an imprint of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

Sophie Duncan

Sophie Duncan is research fellow and dean for welfare at Magdalen College, University of Oxford. She writes about Shakespeare and gender and has worked extensively in theatre and television as a historical advisor. She is the author of Shakespeare’s Women, Juliet, and the Fin de Siècle. She lives in Oxford, UK.