Annie Ernaux on the “Infinite Lack” in Our Search for Love

“Passion fills life to bursting.”

The following is excerpted from Annie Ernaux’s 1988 diary, when she had a passionate and secret love affair with a Russian diplomat—a younger, married man—referred to here as S.

*

December

Saturday 3

More than two months already. I walked past Brummell this evening, at the corner of rue du Havre and rue de Provence. A harrowing beggar, mouth hanging open, holds out some kind of blue wool cap. I retrace my steps and give him ten francs, wishing for S to call me this evening. Four days . . .

10:00 p.m. Why are the signs always there, ironic and astounding? He just called. I think of the beggar, tall, terrible, and full of pain, like Christ, of giving him money, of the phone call this evening. We’ll see each other Thursday. I think of all the things I need to do before then—lunch with Antoine Gallimard, a trip to Luxembourg, especially—and feel exhausted.

Anyway, what does this sign really mean, the phone call from the Latin Quarter? That he’s thinking of me? But in what way? There’s nothing more impossible to imagine than the desire, the emotion, of the Other. And yet, only that is beautiful. All I dream of is this perfection, without yet being sure of attaining it—of being the “last woman,” the one who erases all the others, with her attentiveness, her skilled knowledge of his body: the “sublime affair.”

Tuesday 6

Today, I could not see S because of the lunch with Antoine Gallimard and Pascal Quignard (and I had my period). Am sick at heart because I’m going to Luxembourg, with loathing, for two days. Signs don’t always pan out. Today, I gave money to a beggar at the Gare Saint-Lazare, making a wish for S to call, and later to the punk with all the earrings who got on the train stopped in the station. And then to that singer! We live in a world of mendicancy to which we’ve grown accustomed, almost esthetic. It’s part of the city, the scenery in the station, the tower blocks beyond the tracks with brand names in gigantic letters—“Varta,” “Salec”—high on their sun-lit facades. There was that commercial a few months ago, “Welcome to a world of challenge, the world of Rhône-Poulenc.” You can’t be serious.

I love him (= I need him), and I’m not sure he loves me. Same old story.

It’s been over a week since S has come around. Too long. I review my life since then, and am amazed by how many stupid, unpleasant events there have been: the meal with H, the young people’s book award in Montreuil, the last of my courses on Robbe-Grillet, and the lunch today. That life consists of this accumulation of endeavors, bland and burdensome actions, punctuated only occasionally by moments of intensity, outside of time, is horrifying. Love and writing are the only two things in the world that I can bear, the rest is darkness. Tonight I have neither.

Thursday 8

I’m afraid he won’t be able to come tomorrow because of the earthquake in Armenia. The embassy personnel are run off their feet. Ten very long days, and now maybe nothing. So much longing again this morning, on the train, and then, closer to the time of his arrival, I’m almost frozen with anxiety, the fear of “less”—less happiness, less desire to be together than before.

Friday 9

10:25 a.m. Is that his car?

Fear that he will not come and not let me know ahead of time. Fear, too, that he’s already here. Fear of the moment when I hear the car brake—that sound. Fear of not being beautiful enough, and especially of not giving him enough pleasure. But if I didn’t have all these fears, it would mean I was indifferent.

6:10 p.m. He left at five past five. Barely two and a half hours together. I want to think that the signs of decline were obvious, this time. But he missed Sakharov’s talk at the embassy in order to come to Cergy. Lovemaking was very good the first time, but I didn’t think so the second time. Is he faking? He’s elusive even in his sexual behavior. I don’t know anything about him. This Russian world will remain forever unknown to me—the world of diplomacy, the Soviet apparatus . . . It’s obvious that I’ve always invested too much imagination in men. I get lost, my self dissolves. I don’t know what binds him to me, if it’s just my name, the fact that I’m a writer—it makes me want to run away. The greatest fear is that he has another woman. He was drawn to the title of a book in Spanish, something like “in the arms of the mature woman (madura).” That’s me, of course. And how can I know for sure that certain things do not upset him, such as my inviting Makanine [a Russian writer] to dinner, or the phone call I received from SA when he was with me?

How to interpret his interest in the title, “in the arms of the mature woman” (he says “matured”)? As both fear and recognition of his desire for this kind of woman?

“Are you going away over Christmas?” Does he mean “It would be better if you left, then I wouldn’t have to come see you,” or “It would be nice if you stayed around”?

It may also be that these phrases have no importance for him, but are just the sort of thing that people say . . .

Likewise, his not attending Sakharov’s conference may have been deliberate, political: Sakharov is a dissident, while he is “a loyalist.”

I reread what I wrote last Saturday. Six days, usually nothing, are now an eternity. Passion fills life to bursting.

Sunday 11

Gray day. Reminds me of December ’63, when I was pregnant and wanted an abortion: the university residence, the state of complete and utter dereliction, my desire to sleep in the afternoon (ditto at P’s, in ’84). This kind of sleep (more a huge weariness with life) is comparable to that of winos on benches in the subway. I will probably never spend a whole night with S. I could have done so just one time, in Leningrad, and I didn’t want to then. In ’85 too, the same gray weather, the same melancholy, same dissatisfaction. Right now, I suffer from not writing. Student essays, lessons, emotional life, outings, receptions—it’s all a vacuum. I no longer seek truth since I no longer write, the two are intertwined. I’m also very sexual, there’s no other word for it: being admired, etc. are not what matters to me. What matters is having and giving pleasure— desire, real eroticism, not the imaginary kind, as in hardcore TV or movies.

Evening. I reread the end of the other notebook, and the whole story with S -ashes through my mind. I see how much time has already passed, and I weep. Only beginnings are truly beautiful. Yet in the garden of Sceaux, as at the studio, in October, it was nothing special. So why weep?

I don’t want him to come to my Soviet dinner on Tuesday. It would be too difficult with him there. I love him (= I need him), and I’m not sure he loves me. Same old story.

Tuesday 13

He did not come to my dinner, and it was probably much better that way. I’m not sure that having people here was a good idea. It’s over now. I think I hate to entertain. I live in perpetual anxiety that everything’s a failure (halfway true, tonight). My skirt is stained and there’s a mountain of dishes to put away. I have a mad desire to see S as soon as possible, as if the presence of the others had deepened the lack of him inside me.

What I feel now is a wrenching sensation, a sense of exclusion, the desire for death.

Wednesday 14

He was supposed to call today. For the first time, he didn’t (however, I was out from 4:00 to 8:00 p.m.). The countdown may already have begun. Everything’s so black that I want to stay home. The outside world fills me with horror. Here alone, in this house, it’s less unbearable. And there’s the phone, therefore hope. When I’m out, there’s no escape, I’m a woman on the verge of tears. Tatyana Tolstaya and her “eternal things,” her way of saying, like Nathalie Sarraute, “I am a writer and I am a citizen, the two do not intrude on each other . . .” But all I’ve really retained of her are the “Russian” gestures, shaking the hand in front of the face in negation/derision, and an indefinable facial expression that S sometimes has. I don’t like the way she speaks of her country with derision: “The USSR is a real gift for a writer” (because it’s so terrible).

Thursday 15th

Silence, still. I feel so low that I try to remember similar times: ’58 and ’63 return, inexorably. I know that all it would take is a call (that word is so very apt) to make me want to live again. If one day people read this journal, they’ll see that there was indeed “alienation in the work of Annie Ernaux,” and not only in the work but even more so in her life. My relationships with men follow this invincible course:

a) initial indifference, even disgust

b) “illumination,” more or less physical

c) happy relations, fairly controlled, and even spells of boredom

d) suffering, infinite lack. And then comes the time (I’m there now) when the pain is so all-consuming that moments of happiness are nothing more than future pain, an increase of suffering.

e) The last step is separation, before arriving at the most perfect stage of all: indifference.

8:45 p.m. It’s very hard—much more, I think, than with P, four years ago, in the summer. It is clear that if he doesn’t call me tonight (when he was supposed to call me yesterday), it’s over, for reasons unknown to me (of course, that’s exactly what you never do know, or only find out later). To get through this evening without too many tears is all I ask. Writing doesn’t make you suffer in the same way, though it’s just as hard. What I feel now is a wrenching sensation, a sense of exclusion, the desire for death. At eighteen, I ate to compensate. At forty-eight, I know there is no possible compensation. I imagine a book that would begin with “I loved a man” or even “I still love a man.” When I think of him, I see him naked in my bedroom. I undress him, I think only of his erect penis, his desire. That is how I should tell it.

__________________________________

Getting Lost by Annie Ernaux, translated by Alison L. Strayer, is available via Seven Stories Press.

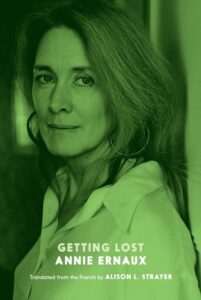

Annie Ernaux

Annie Ernaux is the author of some twenty works of fiction and memoir, winner of the Prix Renaudot for A Man's Place, and of the Marguerite Yourcenar Prize for her body of work, and recently the winner of the International Strega Prize and the French-American Translation Prize and shortlisted for the Man Booker International Prize for The Years. She is now considered by many to be France's most important literary voice.