Anne Lamott on Writing Compelling Dialogue

"Good dialogue encompasses both what is said and what is not said."

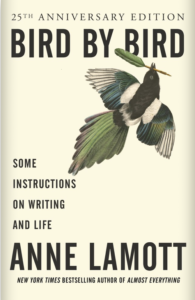

The following is excerpted from Anne Lamott’s Bird by Bird: Some Instructions on Writing and Life and first appeared in Lit Hub’sCraft of Writing newsletter—sign up here.

In the old days, before movies, let’s say before Hemingway, the dialogue in novels was much more studied, ornate. Characters talked in ways we can’t really imagine people talking. With Hemingway, things began to terse up. Good dialogue became sharp and lean. Now, in the right hands, dialogue can move things along in a way that will leave you breathless.

There are a number of things that help when you sit down to write dialogue. First of all, sound your words—read them out loud. If you can’t bring yourself to do this, mouth your dialogue. This is something you have to practice, doing it over and over and over. Then when you’re out in the world—that is, not at your desk—and you hear people talking, you’ll find yourself editing their dialogue, playing with it, seeing in your mind’s eye what it would look like on the page. You listen to how people really talk, and then learn little by little to take someone’s five-minute speech and make it one sentence, without losing anything. If you are a writer, or want to be a writer, this is how you spend your days—listening, observing, storing things away, making your isolation pay off. You take home all you’ve taken in, all that you’ve overheard, and you turn it into gold. (Or at least you try.)

Second, remember that you should be able to identify each character by what he or she says. Each one must sound different from the others. And they should not all sound like you; each one must have a self. If you can get their speech mannerisms right, you will know what they’re wearing and driving and maybe thinking, and how they were raised, and what they feel. You need to trust yourself to hear what they are saying over what you are saying. At least give each of them a shot at expression: sometimes what they are saying and how they are saying it will finally show you who they are and what is really happening. Whoa—they’re not going to get married after all! She’s gay! And you had no idea!

Third, you might want to try putting together two people who more than anything else in the world wish to avoid each other, people who would avoid whole cities just to make sure they won’t bump into each other. But there are people out there in the world who almost inspire me to join the government witness protection program, just so I can be sure I will never have to talk to them again. Maybe there is someone like this in your life. Take a character whom one of your main characters feels this way about and put the two of them in the same elevator. Then let the elevator get stuck. Nothing like a supercharged atmosphere to get things going. Now, they both will have a lot to say, but they will also be afraid that they won’t be able to control what they say. They will be afraid of an explosion. Maybe there will be one, maybe not. But there’s one way to find out. In any case, good dialogue gives us the sense that we are eavesdropping, that the author is not getting in the way. Thus, good dialogue encompasses both what is said and what is not said. What is not said will sit patiently outside that stuck elevator door, or it will dart around the characters’ feet inside the elevator, like rats. So let these characters hold back some thoughts, and at the same time, let them detonate little bombs.

If you are lucky, your characters may become impatient with your inability, while writing dialogue, to keep up with all they have to say. This is when you will know that you are on the right track.

*

Read more on writing dialogue and creating characters:

K Chess on learning dialogue from police transcripts.

David Crystal on the earliest records of spoken dialogue.

Robert McKee on creating convincing characters.

Brandon Taylor on when to protect characters.

*

Books by Anne Lamott

Blue Shoe

Rosie

Hard Laughter

Imperfect Birds

__________________________________

From Bird By Bird: Some Instructions on Writing and Life by Anne Lamott. Reprinted by permission of Anchor Books, an imprint of the Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. Copyright © 1995 by Anne Lamott.

Anne Lamott

Anne Lamott is the author of the New York Times bestsellers Hallelujah Anyway; Help, Thanks, Wow; Small Victories; Stitches; Some Assembly Required; Grace (Eventually); Plan B; Traveling Mercies; Bird by Bird; and Operating Instructions. She is also the author of seven novels, including Imperfect Birds and Rosie. A past recipient of a Guggenheim Fellowship and an inductee to the California Hall of Fame, she lives in Northern California.