Anne Berest’s Best Story Came From Deep in Her Family’s Past

“Every life is a novel for those who are curious enough.”

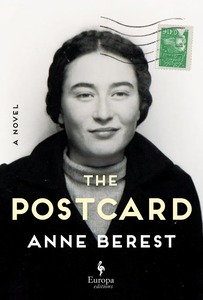

For Anne Berest, the surprise twists and turns of family history are ripe indeed. Berest is known to some for her work as an actor, but is widely celebrated as co-author of the bestselling How to Be Parisian Wherever You Are, co-author of Gabriële, the critically acclaimed biography of her great-grandmother Gabriële Buffet-Picabia (Marcel Duchamp’s lover and muse) and author of The Postcard, a work of family autofiction that became a bestseller in France and was a finalist for the Goncourt Prize when it was published in 2021. The book is now being published in the US.

Berest begins The Postcard with the arrival of an unsigned postcard in her mother Lélia’s postbox in Paris bearing the names of four family ancestors murdered at Auschwitz. As you will garner from Berest’s responses to the Lit Hub Questionnaire, the family had buried its Jewish identity following the Holocaust, her grandmother hesitant to utter the word “Jew” right to her death.

Below, she dives into the power of her own mother as a character and source of creative inspiration, and talks about collecting the stories of elders.

*

What’s the best or worst writing advice you’ve ever received?

Fifteen years ago, for my birthday, a friend gave me a very special gift: a small black box containing a hundred cards. It’s called “The Oblique Strategies,” a card-based method for promoting creativity. I have to confess that I had never heard of this card game, which was created in 1975 by the multimedia artist Peter Schmidt and the musician Brian Eno.

Each card is a suggestion for action or reflection to help in creative situations. For example: “Don’t be afraid of clichés,” “Is something missing?,” “Honor your mistake as a hidden intention,” “Point out the differences,” “Trust yourself now,” “Look closely at the most embarrassing details and amplify them,” etc.

These are just a few examples from the 100+ cards. I find these tips to be very mysterious, very poetic, and in the end, very useful. I dip into them when I must solve a problem with my writing process. My favorite is maybe this one, so true about the condition of the writer: “Not building a wall but making a brick.”

Which of your characters is your favorite?

My mother. She is the main character in my latest book, The Postcard, and she is an inexhaustible source of inspiration. Since I was a child, I’ve observed that people are magically attracted to her, because she is very funny, and she is still a rebel at 80. Before my book came out in France, she was nervous. Imagine that! It’s not easy to be a character in a novel! That’s why, before the book was printed, I asked her to reread it so she could get used to being a heroine.

I told her: “You can cut anything you’re not comfortable with.” The funny thing is that she asked me to change the swear words in her dialogue. “I never talk like that!” she said. In reality, she does… but I cut out the swear words. In France, I promoted the book with her, and it was very pleasant. First, because I was happy to spend time with her (when we were traveling, she made me the same sandwiches she made when I was a child, a true «Madeleine de Proust» as we say in France) and second, the readers were so happy to meet her in the flesh! It’s not often you meet a character from a novel. They were not disappointed, because she is exactly as she is in the book.

In The Postcard, we investigate together an anonymous postcard that my mother received in 2003. We are like two very bad detectives in a thriller: always arguing, and thinking about our riddle … but fortunately, in the end, we solved the mystery.

What was the first book you fell in love with?

When Hitler Stole the Pink Rabbit, by Judith Kerr. This is the true story of its author, who was only nine years old in 1933, living in Berlin in a Jewish family. After Kristallnacht, the whole family was forced to flee.

This book was very important in my childhood for many reasons. As I write in The Postcard, being Jewish was a kind of taboo in my family. My mother didn’t talk about it much—and my grandmother never did, because she was the only survivor of the Holocaust. Her whole family was murdered during the Second World War. After that, she never said the word “Jew” again in her life, because she was afraid it might happen again.

When I discovered When Hitler Stole the Pink Rabbit, I read about the adventures of a girl my age, explaining that she was “Jewish,” the forbidden word. So, I immediately identified with her and found answers in the book to questions I had in my life. That is the main definition of literature for me, what it was in my childhood and what it still is for me: literature offers the answers to the questions you secretly, intimately ask yourself.

What book has elicited the most intense emotional reaction from you?

The dictionary. I will explain why. In 1989, I am 10 years old. My mother, who is a frequent movie-goer, takes me to the movies to watch Sex, Lies, and Videotape, Steven Soderbergh’s first film. I admit, it was a little weird to let a 10-year-old girl watch such a movie, but how can I put this … it was another century and another upbringing!

The ticket seller had assured my mother that there were no sex scenes onscreen: “They talk about it, but they don’t do it.” During the movie, the characters were always using a word I had never heard before: the word masturbation, which immediately fascinated me. So, as soon as I got home, I quietly opened a dictionary, to read the definition. It was a blast. A new world opened up for me, and so I can truthfully say that the dictionary really did elicit the most intense emotional reaction from me.

If you weren’t a writer, what would you do instead?

I don’t know why, but I have always loved, since I was a child, being with elderly people. I always feel good in their company. So, if I weren’t a writer, I’m sure I would have had a job related to the accompaniment of seniors.

At age 25, in order to earn a living, I worked as a biographer. Mainly for the Jewish community, the children hidden during the war, or the children of survivors. I collected the testimonies of elderly people, then I wrote about their lives. No job was more enriching for me than this one. I learned to question people, to weave their story into History, to understand the lines of force that run through the lives they had lived.

It’s a profession that has also taught me how to write characters: each person uses his own words, his own expressions, a vocabulary that belongs to him. A character is above all else a language. I remember questions I loved to ask: Who picked your name? Is it the name of one of your ancestors? What did your grandparents do for a living? What did your mother smell like? Have you lived in other countries? At what point in your life were you happiest? Did someone once save your life?

Listening to the answers, I learned that every life is a novel for those who are curious enough to look into it.

__________________________________

Anne Berest is the author of The Postcard, available now from Europa.