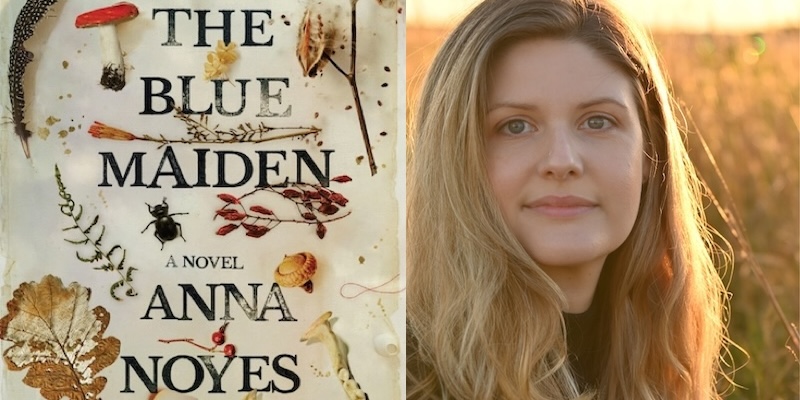

Anna Noyes on How Residencies and New Routines Create New Neural Pathways (and Help You Write Better)

Mira Ptacin in Conversation with the Author of “The Blue Maiden”

Closely examined, the contents of Anna Noyes’s most recent novel The Blue Maiden is redolent of the contents of a toddler’s pockets: a curl of birch bark, the wing of a dragonfly, a seashell and a smooth stone; all treasures when observed at earnest. Step back and look at the whole of it, Anna’s prose is as magical as a full forest, lush and eerie, unsettling and exquisite, a natural work of pure art.

Her second book, The Blue Maiden is Noyes’s earthy tale of sisters Beata and Ulrika, two wild young Nordic outcasts navigating their way on a desolate Swedish island swirling with storms of witchcraft and patriarchy and community secrets. I recently spoke with Noyes about the contents of her pockets, residencies, neuropathways, and writing routines.

*

Mira Ptacin: I’m fascinated by when people take a spark of idea and decide to run with it all the way to completion. And by choice. Please tell me about the initial seed of the idea for this book. How did it come into your mind, and at what point did you determine to commit to it? What did that commitment look like in the beginning?

Anna Noyes: Thirteen years ago I had an inkling my first novel would in some way be about witches. I wrote wild, free-associative prose-poetry around this idea, inspired by writing as a form of channeling or possession. But I put that aside to focus on my short story collection.

Then in 2016 I started a novel based on my Swedish great-great-grandfather. His life story is high drama and begs to be a book. I sold the project on the basis of a prologue—set in Sweden, and focused on the mother and aunt of the character I thought was my protagonist—alongside a pitch for the multigenerational epic I planned to write, following his journey to America and beyond.

Two years and six hundred pages later, I had to reckon with a draft that wasn’t working. But my prologue still compelled me. It felt strange and magnetic and a little wild, something like those old poems. I realized my main character wasn’t the man whose tale I’d been laboriously trying to tell, but that the book belonged—and always had—to his mother, Beata, and her sister, Ulrika.

The story came alive. I realized it should take place on an island (so much of the novel was conceived walking circles around Fishers Island, where I live). And I remembered my old pull toward witch trials.

Most days, I write or do something writing-related for at least a couple hours.

These clues steered me to Blockula, a legendary island-realm once believed to be the Devil’s earthly home. Blockula is linked geographically to the tiny, uninhabited Swedish island of Blå Jungfrun, which translates to “The Blue Maiden.” Rumored grounds of the Witches’ Sabbath—and only reachable by magical flight—Blockula played a key role in the Swedish witch hunts, and especially The Torsåker trials of 1674-75, led by a priest investigating his parish.

In one day, seventy-one people—sixty-five women and six men—were executed. They were marched to their death by the village men, their own families. I was haunted by this, and by the way violences from the past carry into the present. I knew I had the beginnings of the book I was meant to write.

MP: Haunting is truly a good word to use for inspiration. I’m always torn by my true writing process and what I suppose a writer’s routine is. Often, I clean my office out, sign up to run a 10k, pitch other writing projects, adopt a kitten…all things before I have done rather than write my damn first draft.

Do you write daily? Are you disciplined? Do you write in spurts or are you attentive to line by line perfection? Do you create a scaffolding or outline before you write, or are you more spontaneous?

AN: Most days, I write or do something writing-related for at least a couple hours. I’ve struggled with disciplinary ideals (daily word counts, rigid schedules, passing up life-giving stuff because I should be writing) that look productive externally but can be inwardly depleting. I need flexibility within my systems. Now, I’m at home with my twenty-month-old daughter, so the time I have to myself has a welcome sense of urgency.

I like to keep at something in a steady, balanced way. But nearing deadlines (sometimes self-enforced) I’ll go all-out for a shorter stretch—days, at most a month or two—staying up late, working through my free time, weekends and evenings. This is very uncomfortable, but often necessary to pull something across the line, and the adrenaline is galvanizing.

The novel outline that worked for me was also flexible, and evolving. This was a true labor of love—I’d tell my husband my thoughts for the next chapter, each scene or moment, and he’d take down the bullet points on a few sticky notes. Then I’d write the chapter with this mini-outline before our next meeting, so there was some gentle accountability.

It was an immeasurable gift after I’d been alone with the project for so long, and got me (and the book) out of my own head. Whenever I felt overwhelmed, the corkboard of stickies—which square by square became the outline of an entire draft—was a grounding reference point and proof of progress.

MP: Let’s talk about where you write. Personally, I tend to hardly ever leave the little Maine island on which I live, or if I do go to town I go straight to our public library and become a hermit-in-residence, and talk to no one.

Getting out of my routine creates new neural pathways—I’ve had breakthroughs at residencies.

I’m not sure why I haven’t considered attending a writing colony. You’ve been to the best of the best of them. Yaddo. MacDowell. Lighthouse Works. What is the benefits of these residencies? Why do you attend rather than write at home/your studio? What would you say to writers who hope to apply, or hope to attend?

AN: Getting out of my routine creates new neural pathways—I’ve had breakthroughs at residencies. Everyone working and sharing together is energizing, counterbalance to the necessary aloneness (sometimes, loneliness) of my daily practice. I’ve made true friends. And the dance parties! Which speak to what I love most about residencies: community, connection, joy and lightness. Lightness that is possible because they take such care of you—at home, much of the day is spent doing care tasks to keep things afloat.

In residence, an enormous amount of brain space gets rerouted—an unbelievable kindness that someone will bring you meals and clean towels. It is sustenance for the road ahead, a pause for breath. And I leave with lots of new work. But the vast majority of the work takes place at home, in the midst of my busy and lovely everyday life.

If you don’t get in the first time you apply, keep trying. I applied multiple times before I was accepted, and judges and tastes change year-to-year. For me, it also helps to remember that progress, at residencies and beyond, takes many forms—rest, communion, a roomful of women dancing together to “Under Pressure.”

MP: What are your obstacles to writing, whether physical or mental? How do you cope or counter these obstacles?

AN: Self-doubt, shame, comparison, anxiety, distraction, the internet, fear of hurting or exposing those I love, feeling exposed, perfectionism, discomfort with an online presence and with publication, sensitivity and a tender heart (gateways to writing, too), career pressure, deadline-induced panic, being hard on myself.

So I take walks, watch tv, go to therapy, connect with other writers and artists, practice gratitude, spend time with my loves, stay in service to the process, try not to think about it quite so much, have weekly dinners with my neighbors, read, go outside, escape to the mainland, sniff my baby’s curls, bring her to the ocean so she can say its name with a long “o”—”ooooocean”—like a howl.

______________________________

The Blue Maiden by Anna Noyes is available via Grove.

Mira Ptacin

Mira Ptacin is an American author, literary journalist, and educator. Her memoir Poor Your Soul (2016) explores pregnancy loss and was named a Kirkus best book of the year, while The In-Betweens (2019) examines Spiritualism in Maine’s Camp Etna, praised by The New York Times as the best book to read during a pandemic. Her work appears in The New York Times, The Atavist, Harper’s, Tin House, and more. She holds an MFA from Sarah Lawrence College and has taught creative writing at Colby College and the Maine Correctional Center. Ptacin lives on Peaks Island, Maine, with her family, and serves as 2025-2026 Writer in Residence at Mechanics Hall in Portland, Maine.