Ann Beattie Wonders What Donald Barthelme Would Have Made of the Spy Balloon

In Which Barthelme’s Story, “The Balloon,” Gets a Very Close Reading

Donald Barthelme and I were friends, though before we met, I loved—and taught, as a graduate teaching assistant in Connecticut—Come Back, Dr. Calagari. I think about him a lot and miss him (he died too young, in 1989). Though I no longer know where a book of fairy tales is that I had in my New York days, it contained one that hugely amused Donald. It was about two characters named Municar and Manicar, who always greeted each other by asking, “What news today?” When he and I met, sometimes just by coincidence in the Village, other times intentionally at a bar on Tenth Avenue, one of us said, “What news today?”

I wish he’d been here to see the Chinese spy balloon. What would he have liked about this? That someone was being naughty; its audacity; the wonder of it; the way its presence made the day more interesting.

As we now know, earlier ones went undetected. Or no one cared. Initially, I wondered what, exactly, a spy balloon was. Not a plastic balloon you’d see at a birthday party (of course, since Barthelme’s time, those have been superseded by Mylar, and come with pre-printed good wishes). Instrument-controlled, or run remotely by super mice? AI riding inside? What, exactly? The Late Night writers were made so happy by it! Perhaps even school children were crayoning its likeness. (Excuse me: glitter gel penning it.)

Coincidentally, my husband has a new favorite t-shirt that almost depicts a balloon, but instead says, “Is Potato.” (Not as many people ask about this as they do his St. Pierre et Miquelon t-shirt, or the most often questioned, R>G. I don’t think he’d wear a spy balloon t-shirt, though as I write we’re in Key West, so I’m sure many are for sale on Duval street.

In 1966, Donald Barthelme published a story in the New Yorker called, appropriately enough, “The Balloon.” That was so long ago, he might as well have written, “My Afternoon with Dinosaurs at the Plaza.” “The Balloon” is an account that moves from the journalistic (and digressively portentous) to the exhilaratingly poetic, at story’s end. His balloon covers a lot of territory. It contains insider-references, timely and untimely buzzwords, and a sincere wish, I’d say. But more about that later.

Ultimately, it’s not a sendup (no pun intended), because it’s not really satire; it’s simultaneously tongue-in-cheek and achingly sincere. In it, a character narrates an unusual occurrence. Here’s the first paragraph: “The balloon, beginning at a point on Fourteenth Street, the exact location of which I cannot reveal, expanded northward all one night, while people were sleeping, until it reached the Park.”

This is pretty identifiable as a Barthelme beginning. It contains references to things seen and unseen—that’s the wonderful paradox he tries to navigate, as a writer—so that the more we hear of the balloon, the more the small details or word choices also register, letting us know that the balloon, literalized, becomes a symbol for a state of mind: deprivation, caused by love and loss.

One of the many delights of reading Barthelme is his flexibility, his ease with words and concepts that clash, his ability to paint the perfect still life.Reading it, New Yorkers would have immediately understood its terrain, even if unsure (until story’s end) of its parameters. Naming certain streets in New York causes the same kneejerk reaction as the little hammer used on our knee in the Babinski Reflex test: Ah, okay, Fourteenth Street, the dividing line, the line of demarcation, after which you’re (gasp!) hurtling Uptown. The “Park” need not be named; outsiders call it, “Central Park.” And that awkward syntax (“of which I cannot reveal”): who is this self-important jerk? Well, our narrator’s a poseur, presented by a writer who understands something about archness: that people claiming importance or power in this way become sadly ridiculous, as they strain to sound important.

One of the many delights of reading Barthelme is his flexibility, his ease with words and concepts that clash, his ability to paint the perfect still life, in effect (he alludes to painting in the story, in a passage I’ll quote later) by intruding an unexpected, sometimes rude detail whose inclusion makes you see through the pretense. (Think, for example, of Magritte’s portrait of a well-dressed man in a black hat, whose portrait is interrupted by the presence of a floating green apple.)

In this particular story, our narrator has a mission. He’s the (somewhat silly) master of ceremonies, or at least the Maitre d’ of Balloons: Won’t those of us on the sidelines step this way to observe this . . . well, this inconvenient, yet possibly important new presence in the city—a new reality that might shake things up (as the writer always hopes), de-familiarize our world so that we put it back together a little differently; it provides us with a new “landscape.”

Forget the swing set and the slide; the balloon offers a new playing field, a playtime for adults. It can be—as is the story, itself—a game. He writes: “The upper surface [of the balloon] was so structured that a ‘landscape’ was presented, small valleys as well as slight knolls, or mounds. Once atop the balloon, a stroll was possible . . . .” It’s as if the balloon is endlessly pliable—which, of course, it can be in his/our imagination. This balloon was made to be a pop-up book! It was made for storytelling, too, with appropriately writerly gestures used to describe it, and the hint that we, too, might experience a pleasant moment traversing the balloon, taking (I’m guessing) a softer, kinder, art conscious walk through New York.

Imagine how deflating it would be if this was merely a Chinese spy balloon, one subsequently shot down over the water off the South Carolina coast. Barthelme’s balloon has an advantage: it can’t be demolished, any more than the tendency toward hyperbole will disappear from both writing and the way we talk. (Among many other things, this balloon in the incarnation of hyperbole.)

Our narrator-guide has a hidden agenda, not about the balloon, but as a way to locate something tactile, a correlative for his thwarted love and the woman who’s gone to another country, whom he’s missing. A question is implied: How do we talk about feelings, how do we make something real, rather than metaphoric? How do we make it clear we’re overwhelmed, desperately living in our hopes and desires, while daily life passes too slowly?

I read “The Balloon” as a story about the power of love. It’s also a spectacular, ruffly, satin-y Valentine that retains all its sparkle, minus any of those things.Barthelme’s story was written for many people: for readers he draws in and dazzles; as a fine bedtime story for children, who might not really care that the explanation for the balloon’s existence is the ho-hum, yucky love of one person for another; for the New Yorker, where they no doubt appreciated a homey’s local references, as well as his startling brilliance. He also wrote it for himself: Yeah, disguised autobiography, or “autofiction,” or “faux-memoir.” The attempt to define the story’s genre reminds me of Mark Rylance’s character’s often invoked response in Bridge of Spies: “Would it help?”

It’s easy to startle, as a writer. Any good writer can persuade the reader that something unlikely was inevitable. Barthelme’s The Balloon was also launched to let us see the working of a writer’s mind (his). It’s an intimate story, and in it, he spies on himself. In so many ways, in this story, he turns things inside out, to show us fiction’s fabrications, to let us see the stitching. (Well, he was a postmodernist.)

Maybe he was thinking of Roy Lichtenstein’s Ben-Day dot paintings based on comic book frames: the character’s thought balloons containing inane, yet wincingly recognizable, dialogue. In “The Balloon,” he alludes to art high and low: in 1990 MoMA presented a show called just that. Early on, before pivoting and gaining such success as a writer, Barthelme was the acting director of the Contemporary Arts Museum in Houston.

I read “The Balloon” as a story about the power of love. It’s also a spectacular, ruffly, satin-y Valentine that retains all its sparkle, minus any of those things. And the story’s so much more mannerly than the Chinese balloon. Its existence didn’t result in Anthony Blinken’s having to cancel his trip to China. No abashed Pentagon general felt he had to fill us in on previous spy balloon sightings. Barthelme’s balloon didn’t have to factor in biodegradability and the environment. In writing it, he appropriated what was at hand, whether through allusions to visual art, or by selecting perfectly the place where the balloon ends up: West Virginia, a state so often left with our ruins.

For writers, he offers a lesson in timing—how to reveal a story—that sensitizes us to his terrain, both actual (New York) and metaphorical. This story’s also a reminder about the force of the imagination and the power of language. We’ve come to associate reading the word “inflated” with negative criticism to follow, though Barthelme’s balloon, deflated and decoded after serving its purpose, remains buoyant. Inspirational.

___________________________________

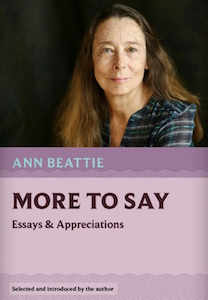

Ann Beattie’s new essay collection, More to Say: Essays and Appreciations, is forthcoming from Godine.