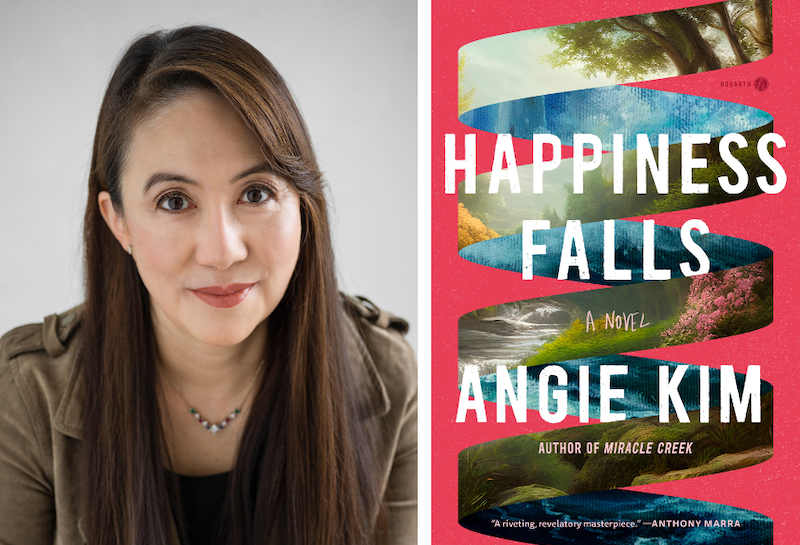

Angie Kim on Measures of Happiness and the Many Forms Intelligence Can Take

Jane Ciabattari Talks to the Author of Happiness Falls

Angie Kim’s second novel, Happiness Falls, is a fast-paced missing persons mystery narrated by Mia, a feisty brilliant twenty-year-old whose family is on the verge of falling apart from the first page. Kim tells me she was working on the novel during the pandemic. “I found it really hard to write,” she says. “I joined a ‘silent zoom’ writing group to force myself to sit in front of the computer, but I couldn’t focus. The pandemic was all-encompassing, with the whole society in emergency mode, and anything not related to it seemed unimportant.”

The pandemic also brought a breakthrough. “I decided to place Happiness Falls in June of 2020,” she says. “Somehow, imagining a family dealing with a crisis during the same quarantine my family and I were experiencing gave me a way into the story and inspired specific scenes and situations. Also, I have some close friends with autistic children who were having an especially hard time with the disruption to routines. Tensions were high everywhere, and my friends were worried about their kids with anxiety and sensory issues melting down in public, not being able to handle wearing masks, prompting bystanders to call the police or Child Protective Services.

“Once I was done, I realized how much elements like wearing masks, the racial tensions involving police interactions, and our society’s changing baselines and expectations not only added to the plot, but reinforced some of the themes I wanted to explore.”

Our conversation explores these themes, and focuses especially on Eugene, Mia’s younger brother, who has a dual diagnosis of autism and mosaic Angelman syndrome (AS).

*

Jane Ciabattari: You open the novel with a mystery: ‘We didn’t call the police right away. Later I would blame myself, wonder if things might have turned out differently if I hadn’t shrugged it off, insisted Dad wasn’t missing missing, but just delayed, probably in the woods looking for Eugene, thinking he’d run off somewhere.” What drew you to write a novel about a missing person—specifically, a missing man?

Angie Kim: To me, missing person cases are the deepest, most intriguing mysteries because the range of possibilities is so vast, encompassing everything from the most horrific (kidnapping and murder) to the most innocuous (took a fun trip without telling anyone). I don’t outline or figure out the plot before drafting, so having this father go missing to begin the story got me to stop procrastinating and start writing—because I knew that was the only way I’d figure out what happened to him.

As for the missing person being a man, you’re right that that was a specific, intentional choice. I have a footnote in the novel that says: “Based on my perusal of the genre, most of the missing are girls/women (87.9 percent), with the missing-men stories all being espionage-or mafia-related.” (That percentage comes from a spreadsheet I made after discussing the missing-girl/woman trope with writer friends several years ago.) The feminist interrogation of women-in-peril stories is nothing new, but I wanted to use this story to explore an additional facet I hadn’t seen: the stay-at-home father overwhelmed (physically and/or emotionally) by the strains of being a full-time caregiver to someone who requires a lot of care, like Eugene. How does the fact of the missing parent being the father, rather than the mother, change the analysis?

Missing person cases are the deepest, most intriguing mysteries because the range of possibilities is so vast.

JC: How did you develop such a driving plot? Were there particular influences, practices, goals while writing the novel?

AK: It came from my trying to reconcile two somewhat contradictory tendencies I have as a writer. One is that I don’t outline or know what’s going to happen before I write. I wish I could—it would certainly make writing a lot more efficient—but I find that I have to do a ton of freewriting to get to know my characters and what they’re doing and thinking before I can start drafting the actual story. With Happiness Falls, I did several years of freewriting (off and on) and ended up with so many seemingly unrelated stories I wanted to tell about this family: different members of the family experiencing different types of racism in Korea vs. the US, the mom teaching the kids Klingon, Mia being called stupid because she looks Korean and can’t speak Korean.

At the same time, I’m a total nerd when it comes to story structure and architecture. I love deconstructing books I admire, finding patterns and trying to figure out how/if they fit into classic storytelling structures with the key plot points coming at certain parts of the book.

I reconciled these two things—loosely-connected stories on the one hand and story structure on the other—by using the missing-person hook as a Trojan horse of sorts. The investigation became a device, a container to hold together all the stories I wanted to tell; by virtue of the father being missing, I wanted readers to consider disparate facets of the family’s past and current lives. The key, though, was that I had to find a way to link the story to the family’s current plight. So many of the twists and turns I could never have thought up ahead of time came out of this process.

I didn’t do this consciously, but looking back, this is what I tried to do in Miracle Creek as well, with the courtroom mystery element serving as a hook to keep the readers turning the pages—with the stories of seven people’s lives inside that frame. It’s not surprising that I love linked stories (Jennifer Egan’s A Visit from the Goon Squad and Anthony Marra’s The Tsar of Love and Techno are two of my favorites), and my favorite form of novel is linked story collections in disguise—books with disparate stories connected by such a strong throughline or mystery element that the stories become unified into one story. Some of my all-time favorites are in this form—David Mitchell’s Cloud Atlas, Emily St. John Mandel’s books, and Tim O’Brien’s In the Lake of the Woods—as well as some recent books I love like Erin Morgenstern’s The Starless Sea and Julia Phillips’s Disappearing Earth.

JC: Why did you choose the independent, inquisitive, scientifically brilliant twenty-year-old Mia as the narrator and lead investigator of this mystery?

AK: Mia’s voice has been with me for years; she was the narrator in a short story I wrote over a decade ago and she just stuck with me. When I began this new story about the same family, I knew Mia would narrate at least a part of—if for no other reason than that I had so much fun with that voice and missed it. Her curiosity was infectious; writing in her voice forced me to research any random thing that happened to pop into my head.

I did consider switching to others’ points of view. But I wanted to do something different from Miracle Creek, which has seven close-third POVs. I came to consider it a personal challenge to stick with one POV for the whole book. A year or so into drafting the book, I fantasized about being in someone else’s head for a while, with the added benefit of learning more by switching perspectives, Rashomon style. That’s when I realized that staying with one character—the claustrophobic isolation, anxiety, and bewilderment—provides a literary taste of what it might feel like to live through a missing-person case, the fear that you might never know what happened to this person you love.

JC: It’s clear from Mia’s account that she knows her family is atypical. As she puts it, there her “boy-girl twin thing” with her brother John, their biracial mix (Korean and white), different last names (“Parson for Dad, Park for Mom—mashed up into Parkson for us kids”), untraditional parental gender roles (working mom, stay-at-home dad). And “indubitably, inherently atypical is with my little brother Eugene’s dual diagnosis: autism and a rare genetic disorder called mosaic Angelman syndrome (AS), which means he can’t talk, has motor difficulties and…an unusually happy demeanor with frequent smiles and laughter.” What influenced your choice emphasize the atypical in this novel?

AK: The answer is probably rooted in my experience as an immigrant. I moved from Seoul to the suburbs of Baltimore when I was 11. Middle school is not a good time to be radically different from everyone else. I craved normality, fitting in—probably not an unusual feeling for preteens and early teens anywhere, but especially for immigrants like me who were bullied and shamed for the differences in the way I looked, dressed, ate, smelled, played, and sounded.

As I grew up and matured, I came to be more comfortable with, and even proud of, my cultural and ethnic heritage, of my non-standard background. But then I had three kids who suffered various types of medical ailments as babies. (They’re all fine now.) Once again, I found myself envious of the normal, the typical—albeit in a different context this time. Why couldn’t I have what everyone else around me seemed to have? Why couldn’t I just fit in?

In many ways, my debut novel was a juxtaposition of these two experiences from my life, as an outsider in a racial/cultural/linguistic sense and as an outsider in a parenting/medical sense, explored primarily through a prism of parenting sacrifice. Happiness Falls does the same, but for one family through the prism of a child—an Asian-presenting, English-speaking daughter and sister who has been labeled as “different” in both Korea and America and who feels like an outsider even within her own family.

JC: What sort of research was involved in creating Eugene’s character—his perceptions and frustrations–and shaping the family life around him?

AK: A lot of my initial research came from real life. I initially thought Eugene had autism, just as his family does at first, and I know a lot of autistic children from group hyperbaric oxygen therapy (HBOT), the subject of my first novel, as well as through speech therapy and auditory processing therapy for one of my kids, who was born deaf in one ear and had dyspraxia (oral motor issues) as a toddler. My spending time with these families over the past 20 years or so definitely shaped Eugene’s character and his family life.

Several years ago, I was researching a particular type of letterboard-spelling therapy for nonspeaking autistic children, and I saw a reference to it being used for children with Angelman syndrome (AS). When I looked it up, I got chills, because what I read matched how I’d seen Eugene in my mind—a huge beatific smile (even when he’s making high-pitched noises out of pain, frustration, or sensory overload), drawn to water, motor impairments, nonspeaking, often diagnosed alongside autism. I instantly knew Eugene had Angelman syndrome (a dual diagnosis along with autism) and that this would play an important role in his family’s story.

My initial research into AS came from reading the medical literature, parent blogs, and advocacy group websites, but by far the most important research came from meeting (in person or via Zoom) families and experts in the tightly-knit Angelman community. I am very grateful to have gotten to interview and spend time with extremely generous people who shared their experiences and knowledge with me and opened their homes to me. Some served as beta readers for early drafts.

JC: You create several key episodes around Eugene’s work to explore the possibilities of being able to communicate with a letterboard. How does this reflect the current research in this area?

AK: To me, this is the heart of the book, so it was crucial that I get it right. If there’s one thing I hope people take away from Happiness Falls, it’s to question the deeply seated assumption most people have that oral fluency is equivalent to intelligence. This is deeply personal for me because of my experience immigrating to the US when I was eleven, not speaking any English. I went from feeling like a smart, talkative, and happy (albeit very poor) girl in Korea to being frustrated and utterly isolated. I felt stupid, judged, and ashamed. Less than. I became fluent in English within a few years, but that experience shattered my sense of competence and confidence for a long time.

My situation was temporary and limited, nothing compared to those with lifelong disabilities, who have beautifully formed thoughts they might never be able to express in any form their entire lives. It impacted me profoundly when I found out that a friend’s nonspeaking autistic son—whom everyone had assumed were severely cognitively impaired, unable to read or write—had learned to express himself by pointing to letters on large boards. It turned out that his inability to speak was due to motor impairments, not cognitive issues. I read essays he’d written—so beautiful and sophisticated that I was skeptical at first, wondering how much “help” the therapist had given him.

I visited therapists and observed sessions in person, and eventually sat with nonspeakers and had conversations with them, with me speaking and them spelling out their responses with no one touching them or helping them to move their arms. I eventually started volunteering at a therapy center nearby, teaching creative writing to nonspeakers. I currently teach three sessions per week—one in person and two virtual—and it’s humbling and astonishing, watching as my students point to letter after letter, all the thoughts they’ve been editing in their heads for so long coming out in polished, complete, gorgeous sentences and paragraphs.

With the caveats that Happiness Falls is a work of fiction and that I’m not a researcher or expert myself, I tried my best to have the novel reflect current research and debates. The most recent studies I’ve seen deal with the concern (discussed in the novel) that nonspeakers are somehow being cued to move their arms to specific letters on the letterboard: a peer-reviewed eye-tracking study out of the University of Virginia by Professor Vikram Jaswal (which I actually mention in my novel) shows that spellers are authoring their own message, and a brain-wave-pattern study by Alexandra Woolgar, a neuroscientist at Cambridge University, to study language comprehension in nonspeakers.

JC: Your title references in part the “happiness quotient.” Mia’s missing father had been studying this concept, she discovers in a notebook found at the park where he disappeared. She is able to study this and the HQ files she finds in his backup hard drive, password protected, which signals her they are important. How did the title evolve?

AK: I’ve been fascinated by theories about happiness for as long as I can remember, and many of Mia’s father’s musings are based on my own scribblings on the topic throughout the years. The first time I heard about the so-called “lottery-winner happiness study,” I recalled my friends in Korea telling me how lucky I was to be moving to America and my parents comparing our family visa to winning the lottery. The disconnect between what I was told I should feel and what I did feel when we immigrated to the US—utter joy versus misery—is something I puzzled over in college as a philosophy major, researching and writing about theories of objective versus subjective happiness.

I’ve been fascinated by theories about happiness for as long as I can remember.

When I started working on this novel, one of the first things I did was to build spreadsheets in an attempt to reduce my ideas about happiness into concrete numbers. (I became a management consultant after I left the law and I love building spreadsheets.) After fiddling around with various hypotheticals, I arrived at a formula involving division, with the quotient representing the predicted happiness level. That’s when I thought, Happiness Quotient, which I thought was the perfect title—I love quirky things, and words with Q in them are inherently quirky, I think—but sadly, no one else particularly liked it. We went through so many iterations of Happiness xyz; my favorite for a while was Variations on a Theme of Happiness. Finally, my UK editor (Angus Cargill at Faber) said, “Have we thought about Happiness Falls”? And everyone kind of fell in love with it, probably all for different reasons (because falls has so many different meanings within the context of this story).

JC: Mia’s father’s study on the “happiness quotient” includes his experiments on his own family re: the question, “Is it possible to manipulate happiness levels, to change your (or your family’s) mindset to maximize happiness and minimize sadness?” Mia’s reaction is complicated, and revealing. How does this HQ concept underpin the novel?

AK: A key aspect of Mia’s father’s HQ concept is that your happiness is relative to your baseline—not based solely on the experience itself, but on the comparison of that experience to your expectations based on your “normal.” As we discussed above, Mia is very sensitive to the concept of normality to begin with, so it made sense that she would evaluate the dramatic ups and downs of the events in the story against this framework (and, conversely, evaluate the HQ framework against what’s happening to her family).

Of course, Mia is not just a character, but the narrator, one who’s writing the story after having gone through these events and after having digested her dad’s HQ writings. So there are aspects of her storytelling itself that incorporate this concept. Her father talks about preparing your loved ones for coming bad news by giving out warnings that get worse over time, little by little. She does this for the readers throughout the story, telling them when something she did will end up making things worse or when something bad is about to happen.

JC: One of the most powerful and distressing elements of Happiness Falls is the attitude Detective Janus and other law enforcement officers investigating this missing persons case have toward Eugene, and their subsequent actions. This lack of understanding and empathy toward a nonspeaking teenager makes Mia’s own investigation central to finding the truth. What research and crafting was required to create this layer of your story?

AK: This is one of the elements that came directly from the stories I was hearing from my friends with autistic children. As their kids were getting older, going through puberty and getting taller and stronger, they were having to contend with strangers misunderstanding their sensory overloads, meltdowns, and loud or physical repetitive behaviors, and calling the police or Child Protective Services, with everything escalating into out-of-control chaos. For many people I know, this is a constant fear.

On the law enforcement and judicial aspects, I’d had some experience based on handling pro bono criminal cases as a lawyer and working at the DC Public Defender Service and the NAACP Legal Defense Fund. I also spoke to lawyers, police officers, and advocates with experience dealing with similar situations—teenagers with disabilities, particularly nonspeakers, who get thrust into the criminal juvenile system. It’s a rapidly changing and growing area, which made it challenging but also fascinating; for example, Virginia passed a statute establishing a new autism defense when I was in the middle of writing the story, steering it in a totally different direction.

JC: What are you working on next?

AK: I’m at that stage of my work when I’m in love with the idea—kind of like the beginning of a romance, when it’s more of a crush and you’re not quite sure how it’s going to develop—so I’ve decided to let it be for a while without talking about it for now. I have a footnote about this in Happiness Falls, how giving voice to an idea triggers you to evaluate it, thereby exposing the flaws that the initial excitement blocked. I’m not ready to see the flaws in the idea quite yet, so I’m holding it in like a delicious secret even though I’m so excited about it and dying to talk about it.

__________________________________

Happiness Falls by Angie Kim is available from Hogarth Press.

Jane Ciabattari

Jane Ciabattari, author of the short story collection Stealing the Fire, is a former National Book Critics Circle president (and current NBCC vice president/events), and a member of the Writers Grotto. Her reviews, interviews and cultural criticism have appeared in NPR, BBC Culture, the New York Times Book Review, the Guardian, Bookforum, Paris Review, the Washington Post, Boston Globe, and the Los Angeles Times, among other publications.