Anatomy of a Kidnapping: An Inside Look at the First Few Days in Terrorist Captivity

Shahbaz Taseer Recounts the Beginning of a Four-And-A-Half Year Long Nightmare

The first thing that struck me was the smell.

I found myself alone in a mud-walled room with straw and animal feces scattered across the dirt floor. My hands and feet were bound with metal cuffs. It was dark; what little light there was slipped in through a small hole in the ceiling where a pipe passed. The stifling heat left me feeling faint. Randomly placed in the corner was a red bucket, which was to serve as my toilet. There was no mattress. The floor would be my bed.

The pungent odor was the first thing that hit me as I regained consciousness. It was unbearable and turned my stomach. It wasn’t just the room that smelled; I did too.

My immediate thoughts: Where am I? Will I ever see my family again?

Just a few days earlier, I had been at home, in Lahore, Pakistan. It was a normal day like any other. My routine was to wake up, get dressed, and take a ten-minute drive to my workplace. To my complete shock and horror, I was ambushed on my way to work, beaten, and drugged. Waking up to unfamiliar surroundings. Shackled.

I felt like a ghost, traveling to hell.

This was now my world.

How can your whole life change in an instant? How can everything you know and trust and depend on, every person you love, every comfort you’ve come to enjoy and embrace, disappear in a moment and be replaced by pain, loneliness, and despair? When that happens, how does one go on?

Would I survive?

These were questions that, it turned out, I would have four and a half years to contemplate.

*

As I sat, clueless and groggy, on my very first day in that sweltering, filthy room, I had more pressing considerations. My natural survival instincts were triggered and I began to make a mental checklist.

Figuring out who had taken me, and why, and what they wanted, and whether I could give it to them and get home safely. As I struggled to get my bearings, two immediate thoughts crossed my mind.

I must be in Afghanistan. And I’m going to be beheaded.

I was familiar with stories about kidnappings in Pakistan and knew of people who’d been abducted. In most cases their captors would demand a ransom; however, on occasion it was just to make a gruesome, violent statement, leaving a brutal video for the world as proof of their seriousness and their insanity.

As I’d learn much later, my captors had done both.

I discovered that, less than an hour prior to my arrival, the room I was being held in had been used as a holding pen for sheep to be sacrificed for a Ramzan feast. This, in part, explained the smell. In the punishing late-summer heat, the room stank like a barnyard, or a slaughterhouse. And I didn’t smell any better.

It had taken my captors three days to transport me here—wherever “here” was. I assumed I had been ferried to Afghanistan, but it could have been Pakistan. It was hot and dirty, buzzing with mosquitoes. Beyond that, I knew nothing. Clearly, my location didn’t matter; I wasn’t leaving anytime soon. I was restrained by chains, completely immobilized, similar to a death row criminal. I’d been stripped and dressed in a woman’s soiled shalwar kameez, now also covered in caked blood and vomit, which I assumed were my own. My jaw was swollen and throbbing, and I had an open wound over one eye. The chains that bound me were fastened to a metal loop in the floor, the kind you’d use to restrain an animal—for example, a sheep—waiting to be killed.

The three days I’d spent traveling to this place were lost to me in a fog. After I was snatched from my car on a busy street in an upscale neighborhood, I’d been blindfolded, beaten, and injected with ketamine, a horse tranquilizer, to keep me unconscious. My captors stuffed me into the back of a car, wedged down on the floor, and kept me out of sight. Whenever I stirred, I was kicked into silence.

On the first day they took me, we eventually arrived…somewhere. Having been abducted on a Friday morning, dragged into an empty house blindfolded, I woke up on what I assumed was the following day. One of the captors recklessly pulled the pin from a grenade and placed it in the palm of my hand. He moved within an inch of my face and hissed in my ear in Urdu, “Have you ever held one of these before?” Later, he shoved a gun into my mouth and psychotically asked, “Have you ever seen one before?” I wasn’t sure what he wanted me to say. I babbled something about money, about obedience. About how I’d give them what they wanted if they released me.

“You’re a valuable treasure,” he shouted. “The whole country is looking for you.” He yelled so as to frighten me. It definitely worked.

When this man wasn’t terrorizing me, he’d reassure me in calming whispers, which was even more unnerving. “Don’t worry. You’ll be home soon.” He explained that he would collect the ransom and release me, and this would all be wrapped up in a day. Maybe two.

When I’d first regained consciousness, I thought I was in a grave. In a way, I was.

His mocking laughter was followed by blows to my head, and a syringe full of ketamine.

Everything about the days right after my kidnapping was obscured in that ketamine haze—a half-remembered barrage of beatings and druggings and barked commands and darkness and barely recollected images. I recall waking up in the back of a car, begging them to stop so I could step outside and urinate. Someone in the car handed me a bottle. They all wore masks. I felt like a ghost, traveling to hell. I started pleading with them to let me step outside by the road to relieve myself. “You’ve beaten me, you’ve cuffed me, you’ve kept me on the floor,” I yelled. I kept jabbering. I was petrified.

“I don’t need this!” the driver shouted finally. “Put him out!”

More ketamine.

*

My next lucid moments were at an army check post on the outskirts of Lahore. I could barely see. I was in a burka. My captors had disguised me as a woman and sat me up between two of the men in the backseat. As one of the men held a knife to my side, its point perilously close to cutting into me, he whispered, “If I hear a sound, I’ll gut you!”

I was unaware that the whole country was looking for me; my kidnapping had become national news. The ISI, Pakistan’s intelligence agency, had found the safe house where I’d been held the day before. They’d found my broken sunglasses, and a syringe, used to inject me with ketamine, with samples of my blood in it.

I tried to get a sense of what was happening through the netting of the burka’s eyeholes, but the headpiece had twisted to the side. I was drenched from head to toe in perspiration from the searing heat and the ketamine coursing through my body. The heavy black material of the burka clung to me, as stifling as a death shroud. When I’d first regained consciousness, I thought I was in a grave. In a way, I was.

Two young officers, their machine guns slung over their shoulders, gave the car a quick once-over, glancing at all of us, then waved us through.

*

Repeatedly injected with ketamine to sedate me, I still had no idea where we were as we drove into a small town. It was approaching dusk on this early evening, still daytime. My captors drove aimlessly, killing time, waiting until sundown when everyone would break their fast, allowing my captors to spirit me away in the darkness without drawing attention.

As the sun set, the nondescript car was parked. I was moved inside a low, mud-walled building and into the squalid cell where I regained consciousness. This room with the single red bucket and the disgusting, nauseating smell was now my world.

*

The ketamine forced an uncontrollable vomiting, which covered me in bile that hardened. I’d never before smelled this putrid in all my life.

My entire body ached from the physical violence from the past few days. Medical attention was certainly not an option.

My captors came and went, wearing scarves to mask their faces. They were young men, I could see that now. One of them looked no older than thirteen. They spoke an unfamiliar language. Later I would learn they were from Uzbekistan. We couldn’t communicate or understand one another. The two or three guards in charge ignored me. Alone, I listened to the monstrous buzz of the mosquitoes. They came in great swarms, in and out of that single hole in the ceiling. A deafening racket that still irks me to this day.

I began thinking about The Matrix. It was one of my favorite movies. I was obsessed with it when I’d watched it as a teenager. My friends and I ditched our baggy, hip-hop-inspired styles for slim black jeans and slick black overcoats. I got new sunglasses. I saw myself as Neo. I wanted to take a pill and escape the comfortable fantasy world I’d been living in to see how the world really worked, in all its horror and grittiness.

Now it had happened, except someone else had forced the pill down my throat. My old world had disappeared, almost as if it never existed. As though it were a dream, I was in this new world, which felt like a nightmare I couldn’t wake up from.

As I sat there, terrified, alone, I wondered if there was any chance of my going back again.

As though it were a dream, I was in this new world, which felt like a nightmare I couldn’t wake up from.

Beyond that, I knew nothing, not where I was, who had taken me, what they wanted, what my family knew, when it would end, or how.

What was undeniable was that I was on my own.

For the very first time in my life, I was completely isolated.

Alone.

*

If I had known, on that very first day, that I would spend the next four and a half years of my life in captivity, I do not think I would have made it. The one consolation of my first few days was that I believed that my ordeal would soon be over. My family would find a way to meet my kidnappers’ demands and set me free, or they would kill me. It seemed this couldn’t drag on for weeks, months, let alone years.

Looking back, I find it hard to believe that’s what actually happened.

Yet it did. I know. I was there. I lived through every ugly moment of it.

On the first day, every so often, someone would come in to check on me or drop off a meager meal. Sometimes, they would tell me he was coming. He was on his way.

“Who?” I would ask.

I had no clue who they were talking about—this man who would hold my life in his hands for the next four and a half years.

Then, one day, weeks later, he arrived.

That’s when my ordeal truly began.

__________________________________

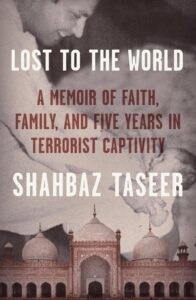

Excerpted from Lost to the World: A Memoir of Faith, Family, and Five Years in Terrorist Captivity by Shahbaz Taseer. Copyright © 2022. Published by MCD, an imprint of Farrar, Straus and Giroux, a division of Macmillan, Inc.

Shahbaz Taseer

Shahbaz Taseer is a Pakistani businessman, and the son of the former Governor of Punjab (Pakistan) Salman Taseer. Taseer was held in captivity for around four and a half years and was recovered from Kuchlak, Balochistan on 8 March 2016. His kidnapping was referred to as one of the most high-profile kidnappings in Pakistan by The Guardian.