An ode to Stranger Than Fiction, the best movie about writer’s block.

On this glorious day, 15 years ago, Stranger Than Fiction came into the world. It is arguably the best movie about writer’s block, dramatic irony, fate, the unknowability of death, and the gray space between what is “real” and what is fiction. If you haven’t seen it, I regret to inform you that it was rudely taken off of Netflix this summer, and that you can’t even rent it on YouTube, but never fear! I have taken it upon myself to recount the plot in excruciating detail. Here we go:

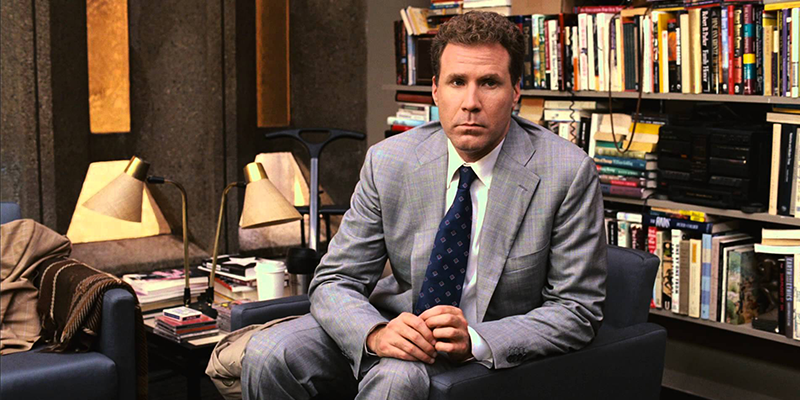

Harold Crick (Will Ferrell) is an IRS agent who lives his life strictly by numbers, guided by his trusty wristwatch. In the opening sequence, for instance, we watch him get out of bed at exactly 7:15am, brush each of his 32 teeth 76 times, etc. We watch him jog to catch the 8:17 bus, arrive at work, do insane mathematical calculations in his head, take a 45.7 minute lunch break, and return home alone, where he will have a solitary dinner and adjourn to bed at 11:13 on the dot. We know these precise digits because they are relayed to us through a voiceover (Emma Thompson). And then there is a genius break in the narrative/fabric of reality.

It’s a Wednesday (much like today) when Harold Crick starts to actually hear the narrator speak about his life. At some point later in the movie, he describes it as someone describing his every thought and action—with much better vocabulary. Not knowing what else to do, Harold tries to ignore the voice and goes about his day as normal. When his watch goes haywire and he has to reset it by the time of a stranger, that’s when things take an even bigger turn. That’s when he hears the voice say, “Little did he know that this simple, seemingly innocuous act would result in his imminent death.”

So begins Harold’s quest. His first stop is obviously a psychiatrist. Harold confesses that he believes himself to be inside some sort of novel, so he is referred to a literature professor (Dustin Hoffman), who indulges his seemingly delusional state and becomes intrigued by the narrative devices at play. (“Little did he know”—a flare of dramatic irony.) They try to determine whether he’s living in a tragedy or a comedy. As an experiment, he stays home and does absolutely nothing for a day—and a bulldozer crashes through his walls and nearly kills him. (Tragedy.) On the other hand, he has just met a lovely lady, Ana Pascal (Maggie Gyllenhaal), whose bakery he has been assigned to audit. (Comedy.) There is one heart-melting scene in which he brings her flours. Get it? Flours, instead of flowers. Because she’s a baker. Flour. The whole movie is a love letter to language!

Meanwhile, the audience gets to meet the voice, a woman named Karen Eiffel. She’s your typical, tortured, muttering, cigarette-smoking writer, always lost in her own world. She’s suffering from writer’s block. She just can’t quite figure out how to kill Harold Crick. (Enter an assistant that her publisher sends over to help her finish the manuscript. I’m skeptical that this is actually a thing that happens, but I will take any excuse for Queen Latifah to appear on screen.)

Essentially, Harold figures out who his author is, and he confronts her. They meet. Unfortunately, she has already made her mind up about the ending. It is decidedly the best, most beautiful thing she has ever written in her entire career, a true masterpiece. Knowing that his death will have greater meaning, he marches bravely towards his fate. In his final days, he leaves his job, learns guitar, and loves Ana Pascal with his whole heart.

(Spoiler alert.) The author lets him live. It makes for a weaker story, sure, but in the end, she decides that Harold Crick—a selfless, noble character, as it turns out—is the kind of person you want out in the world.

These days, the world seems to be playing jumprope with the line between fact and fiction. Every day, literary Twitter debates the ethics of spinning stories from real life, of pocketing people you really know and placing them in the pages of a book. I’m not saying that Stranger Than Fiction argues against this. It was made long before Cat Person and the Kidney Story. The moral, if any, is more carpe diem than code of ethics. Still, if we are to glean anything from Harold Crick’s newfound freedom, it’s that maybe we should surround ourselves with the people who believe us, who believe in us, who make us happy, who bring us flours. Maybe it was about surrounding ourselves with the Good Art Friends all along.

Katie Yee

Katie Yee is a Brooklyn-based writer.