An Interrogation of Identity as a Hyphenated Man

Omer Aziz on Finding Himself Trapped Between East and West in Jerusalem

The door closed in a brightly lit office. A soldier in a green uniform stood at the side. The interrogation chamber was about to swallow another body. I sat in a chair, quiet and afraid. My eyes were fixed on the ground that now felt like quicksand. In America, I would have known what to say and do. But I was no longer in America. I was in Israel.

An hour passed, then another. The room was quiet, and except for the rush of thoughts, I was still. It was like those days of youth when I sat in the mosque and tried to talk to God. Now I was older and knew that God didn’t talk to people in interrogation rooms.

A young soldier, boyish and hesitant, watched from the doorway. He must have been 18, 19 tops. Our skin tones and facial features were similar. He reminded me of my boyhood friends back in Toronto, and in an amusing sort of way, resembled my younger self: in an alternative universe, our positions might have been reversed.

Despite being innocent of any wrongdoing, I could not understand why I still felt guilty.

A short, bald man entered the room. He had a folder under his arm, the reserved demeanor of a man in control.

“I am Max,” he said. He rolled up his sleeves, sat across from me, and stared.

“Where are you from?” he asked.

“Canada,” I said. “But I study in America.”

“Omer …” he said. “This is a Hebrew name. You are Jewish?”

“No,” I said, almost as an apology.

“Where is your family from?”

“Pakistan,” I said.

Max’s eyebrows went up. He ripped off a piece of paper and slid it toward me. “Write here your father’s name. Write your father’s birthplace. Write your grandfather’s name, grandfather’s birthplace, and all the relatives you have in Pakistan, Canada, and America.”

I stared at the blank paper. I had been to Pakistan only once, when I was a boy, and had no memories of the country. I wasn’t even sure how many relatives I had there anymore. My link to that nation existed through my parents and the culture I carried with me, a product of history, migration, and colonization. Pakistan was an imaginary homeland.

My hands grew sweaty. I rubbed them against my jeans. In an instant, I could see the chasm between the idea I had of myself—law student, reader, writer—and the perceptions forming in Max’s eyes. I answered his questions. I wrote my grandfather’s birthplace as “British India,” but I did not know anything else. I did not even know my own history.

Over the next four hours, Max asked me every possible question about my life. He asked if I practiced Islam, asked why I had come to his country, asked about my parents and friends. It was not lost on me that Max’s own ancestors might have been put in ghettos, that he might have also been a descendant of the colonized.

I regretted my decision to come on this trip, the only Brown person to join, the only person to be interrogated.

Here was the truth: I was not a terrorist but a tourist, in my second year at Yale Law School, visiting the Holy Land with my peers so that we future lawyers could understand Israel and Palestine. In one way, this interrogation room was familiar, since I had been questioned all my life about my identity and religion.

I could have been at any border crossing in the West, no longer an individual but viewed as part of the Brown mass gathering at the barbed-wire fences of our democracies. Straight-haired, lightly bearded with brown skin, I had the sort of face you might have seen on the television screen, every day and night, for over 20 years.

Now I regretted my decision to come on this trip, the only Brown person to join, the only person to be interrogated. Despite being warned of this possibility, I decided to go anyway because of the ideas I held in my heart: that one must live “as if ” the trials of race and belonging did not exist, rising above prejudices and stereotypes, acting so free that one’s very presence was an assault on the systems of injustice.

Growing up after 9/11, I had found it impossible to craft a coherent identity when the whole world seemed to be losing its mind. My parents, immigrants and Muslims, were conflicted about how I should approach the world: to assimilate entirely or hold fast to my roots. I was torn within myself, trying to be two people at once, part of two cultures, finding acceptance in neither. So I boomeranged between invisibility and presence, between misperception and clarified reality, always trying to blend in, chameleon-like, with my environment. I had become a hyphenated man; no, I was the hyphen.

Even as the interrogator’s pen clicked and the clock ticked, another question formed in my mind: What kind of dream had I been pursuing all these years, trying to educate myself out of my own skin, reading every book I could get my hands on, separating myself from my past, that in a single instant this stranger could put me right back into the box from which I sprang? Did I seriously think that I could escape from my tribe, liberate myself from the ordeals of Brown people, my people? How could I be so naive to believe that by “earning” the right badges and degrees, I might convince the inquisitors of the West that I was a worthy human being? I had unconsciously come to believe a lie.

At the end of a long four hours, the very identity—the mask—that I had carefully cultivated was peeled off like a false skin, leaving only the naked face underneath.

Eventually, I was free to go. “Let us know if you make any friends while you’re in town,” Max said. I did not answer him.

I got into a taxi with a white American friend, who asked how it went. I could not bring myself to speak, but I was burning inside.

We drove toward Jerusalem. The rolling hills passed us by, one of those beautiful Levantine evenings that seemed to portend the beginning and the end of worlds. And against this beautiful backdrop, I could feel the old fear and anger stirring in my chest, emotions I had taught myself to keep rigidly caged. I had learned the hard way that while the unexamined life might be more blissful, the examined life—from the eyes of a Brown boy—is a long trial: a crucible, or a crusade, set at the border between East and West.

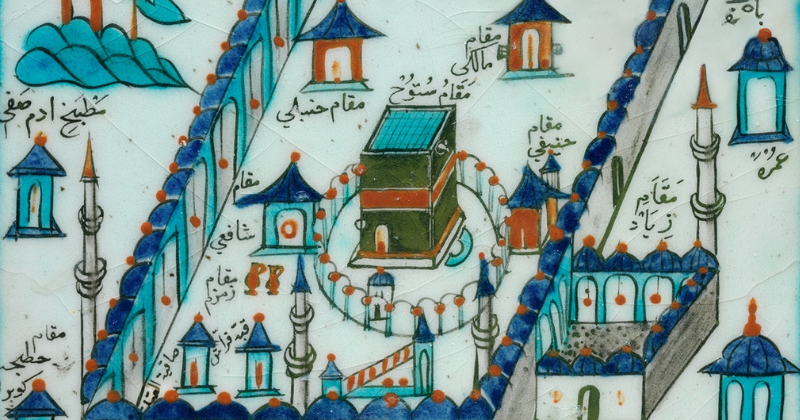

Three days later, I awoke early in the morning and walked with my friends to the Dome of the Rock. I had already worn a yarmulke and prayed at the Western Wall, had seen pilgrims falling to their knees in the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, had watched as countless soldiers with machine guns watched me. I wanted to visit the Haram al-Sharif, or Dome of the Rock, the third holiest site in Islam, where it was believed that the Prophet Muhammad had flown to the heavens. I wanted to bring a Qur’an home for my mother.

As I walked, I was cognizant of my every move. I felt the alienation like rocks under my skin, an outsider, in conquered territory, among dueling histories and tragedies. I thought that after my treatment by the interrogators I would be welcomed in the holy mosque the minute I stepped inside and recited the ritual greeting of As-salamu alaykum. Peace be upon you.

I went through multiple checkpoints in the Old City and soon arrived at the stone steps. The mosque was brilliant, palatial, the golden dome glinting in the sunlight, the blue calligraphy harkening to centuries past.

An old man, the mosque’s guardian, was standing outside the door and watching me and my friends. He had a tasbih in his hands and a gray beard that went to his chest. I had spent many years as a boy attending a madrassa in Toronto, so I knew what to say and how to carry myself. I told my friends I was going inside—technically, only Muslims were allowed to enter the old mosque, one of the few privileges I thought was mine.

The old man disappeared inside the masjid. I paused, considered waiting until he was back so he did not think that a Western traveler he had just seen taking photographs was trying to sneak into this place of worship. Once again, I doubted my place in my community, felt the need to adjust and wait, lest I be seen as an intruder. Then I decided, not for the last time, to act “as if ” I belonged.

I walked slowly, the seconds stretching out with each step I took. Only when I crossed the threshold to the mosque did the old man see me.

He grabbed my shoulders and pushed me outside the door. My friends watched in horror as several guards rushed over to me.

“Who are you?” the old man shouted.

I stumbled over my words.

“Where are you from?”

I told him.

“You are a kaafir,” he said, a nonbeliever.

He said something in Arabic to the security guards around me. It was apparent that they all believed I was an impostor, an interloper, a Westerner invading their peace.

“But look at my passport,” I said desperately, showing the blue badge of privilege.

The old man stared at the photograph and name. “Omer … Umar … Umer … This is a Muslim name …” He looked confused, as though I was trying to deceive him.

Suddenly, the man’s eyes grew wide and he pointed a finger upward. “Recite!” he claimed. “Recite the Shahadah!” He was asking me to state the declaration of faith, the single sentence of Arabic text, known to all Muslims, attesting that there was no god but God, and Muhammad was His Messenger. It was literally written above our heads on the walls of the mosque. I recited it quickly, stumbling through the words, my voice choking. The old man shook his head. I had made a mistake in my pronunciation.

“Recite,” he said. “Recite.”

Now I was surrounded by more people. Terrified, I fell silent. I was ready to flee, just like I had done in the days of my youth from the boys on the block. I felt shame. Here was the one place I thought I would be welcomed, and yet it was also here that I felt most like a stranger.

Everywhere I went there had been an implicit question everyone seemed to be asking: What side are you on?

I turned to leave, hating myself for failing to convince my own people that I was one of theirs. Several older women, their heads covered, came to see what the commotion was. They looked from my face to the old man’s and smiled to themselves, patiently explaining to him that there had been a misunderstanding.

“Let the brother in,” one of the women said.

The old man, realizing he had made an error, turned to me. “You young men have gone into evil ways,” he said. “You have become hostages to false gods, have become too Westernized. You have lost your faith and lost your history.”

I nodded along with his lecture, even though I wondered whether the West was not my true home. When the crowd dispersed, I felt rage: unable to belong anywhere, forced to show my papers everywhere, yearning for some community of my own. But I had sympathy for the old man, who could have been my grandfather, a man living under occupation and accustomed to Westerners strolling through this ancient plateau like they owned it.

Outside the mosque, I heard shouts and chants. An even greater disturbance was beginning.

“Allahu Akbar!” the voices shouted. Other voices responded in Hebrew. The security guards moved past me to see, and before my eyes, I watched as Jewish settlers and Palestinian residents squared off in the distance: the West and the East, clashing. As the chaos grew around me, I found myself once again caught in the middle.

Everywhere I went there had been an implicit question everyone seemed to be asking: What side are you on? It should have been an easy question to answer, given that English was my first language, that I was born to a working-class immigrant family in North America, and the journey I went on took me from a little corner of Toronto to Paris, Cambridge, Yale Law School, places I believed would allow for my rebirth as a true Westerner. Over time, I had been transformed into someone I no longer recognized. Over time, my mask had disfigured my face.

I stood at the entrance of the mosque with brown skin and an empty stomach, and it was there, amid the torrent of hurt and fear, that the reality of running from myself, being rendered invisible, marked as an outsider, defined by others, and forced to confront the coldness of the human heart in all its forms—it was only then that the wounds opened up the past, and the story returned to me.

__________________________________

From Brown Boy. Reprinted by arrangement with Scribner, an imprint of Simon & Schuster. Copyright © 2023 by Omer Aziz.

Omer Aziz

Omer Aziz is the author of Brown Boy: A Memoir and a Radcliffe Fellow at Harvard University.