An incomplete history of Cat on a Hot Tin Roof: the good, the bad, and the ugly.

Cat on a Hot Tin Roof—Tennessee Williams’ sultry southern storm of a play about greed, deceit, self-delusion, sexual desire and repression, homophobia, sexism, and the looming specter of death—has had a curious life. Indeed, you could argue that Cat has actually had three different lives since Williams dreamt it up in the early 1950s: Williams’ original text (initially buried but later revived), Elia Kazan’s original Broadway production (which won Williams the Pulitzer Prize for Drama in 1955), and the Paul Newman- and Elizabeth Taylor-starring movie adaptation (which, despite its Hays Code neutering, was perhaps the most sexually-charged mainstream American film of the 1950s and an Oscar-nominated phenomenon back in 1958). If you’re a Tennessee Williams fan (and how could you not be), chances are you’ve seen the movie and/or some version of the original text (which Williams tinkered with and restored for the first Broadway revival in 1974, and which has been used for most revivals since).

Since this year marks the 65th anniversary of the play’s Broadway premiere, I thought I’d track down some fun, and not-so-fun, facts about the many incarnations of Williams’ masterpiece.

But first things first, a brief recap of the story:

Set in the Mississippi plantation home of Big Daddy Pollit, a domineering cotton tycoon and patriarch of a viperous family in turmoil, on the dual occasion of his 65th birthday and (alleged) clean bill of health, Cat on a Hot Tin Roof focuses on the tempestuous relationship between his grieving, alcoholic, probably closeted former star athlete son, Brick, and Brick’s fiery, outspoken, unapologetically sexual wife, “Maggie the Cat”; his scheming elder son and daughter-in-law and their weaponized brood of “no-neck monsters”; and the terminal cancer diagnosis of which all in the Pollit clan but Big Daddy and Big Mama have been made aware.

Now, on to the Fun and Not-So-Fun Facts:

Not-So-Fun Fact #1: Despite having already conquered Broadway with The Glass Menagerie (1944) and A Streetcar Named Desire (1947), by 1955 Williams’ reputation had been dented by the failure of his most recent play, Camino Real, and the playwright was desperate for another win. Kazan, on the other hand, was coming off the runaway success of On the Waterfront (which won eight Oscars in 1954, including Best Picture and Best Director for Kazan). Kazan wanted a reluctant Williams to change the third act to one in which Maggie was shown more sympathetically, the dying Big Daddy reappeared, and Brick underwent some form of moral awakening. As Williams’ (pretty humbling) note on the text indicates, it was the director’s vision that ultimately won out.

It was only the third of these suggestions that I embraced wholeheartedly from the outset, because it so happened that Maggie the Cat had become steadily more charming to me as I worked on her characterization. I didn’t want Big Daddy to reappear in Act Three and I felt that the moral paralysis of Brick was a root thing in his tragedy, and to show a dramatic progression would obscure the meaning of that tragedy in him and because I don’t believe that a conversation, however revelatory, ever effects so immediate a change in the heart or even conduct of a person in Brick’s state of spiritual disrepair.

However, I wanted Kazan to direct the play, and though these suggestions were not made in the form of an ultimatum, I was fearful that I would lose his interest if I didn’t re-examine the script from his point of view. I did. And you will find included in this published script the new third act that resulted from his creative influence on the play. The reception of the playing-script has more than justified, in my opinion, the adjustments made to that influence. A failure reaches fewer people, and touches fewer, than does a play that succeeds.

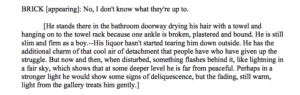

Fun Fact #1: Williams’ original character descriptions and stage directions are literary gems in and of themselves:

Not-So-Fun Fact #2: In March 1958, during the first week of shooting the Richard Brooks-directed film adaptation, Elizabeth Taylor contracted a virus, causing her to cancel plans to fly to New York with her then-husband, the producer Mike Todd. Todd’s plane crashed, killing everyone on board.

Fun Fact #2: Both Tennessee Williams and Paul Newman were incensed by the film’s screenplay, which removed almost all of the play’s homosexual themes and revised the third act section to include a lengthy scene of reconciliation between Brick and Big Daddy. Allegedly, Williams so disliked the toned-down film adaptation of his what he considered to be his greatest play that he showed up at a movie theater and told people in the queue, “This movie will set the industry back 50 years. Go home!”

Fun Fact #3: The iconic poster art for the film was created by American realist artist, and giant of the 1950s Hollywood monster movie poster game, Reynold Brown.

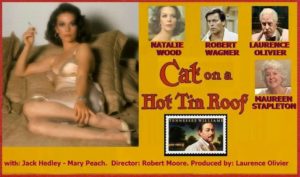

Not-So-Fun Fact #3: In a 1976 television version of the play, Brick and Maggie were played by the real-life husband and wife team of Robert Wagner and Natalie Wood…?

Fun Fact #4: On stage and screen, Jessica Lange, Ashley Judd, Kathleen Turner, Mary Stuart Masterson, Anika Noni Rose, and Scarlett Johansson have all played Maggie; Tommy Lee Jones, Ian Charleson, Brendan Fraser, Jason Patric, Terrence Howard, and Benjamin Walker have all played Brick; and Burl Ives, John Carradine, Ned Beatty, James Earl Jones, Ciarán Hinds, Rip Torn, and Laurence Olivier have all played Big Daddy.

Dan Sheehan

Dan Sheehan is the author of the novel Restless Souls (Ig Publishing) and Editor-in-Chief of Book Marks.