An Eye On the Court: Chronicling 40 Years of NBA Photography

Dave McMenamin on Nathaniel S. Butler’s Pioneering Work Capturing Some of Professional Basketball’s Greatest Moments

For forty years, Nathaniel S. Butler—or Nat, as he’s known to his countless friends and colleagues—has navigated the hustle and bustle of New York City to arrive at the corner of Eighth Avenue and Thirty-Third Street and clock into work with his trusty camera at his side.

Only Butler doesn’t report to your typical office building.

“There’s just something about Madison Square Garden that is truly magical,” Butler says.

For four decades Butler has captured the action on the basketball court inside the “World’s Most Famous Arena” on his camera, and those images have made their way around the globe. “The Garden is bigger than basketball,” Butler says. “An Ali-Frazier fight. Concerts. The Beatles and Elvis. And I think that does lend to the aura of the building…it is bigger than basketball. I happen to be focused on the basketball part.”

Charles Barkley; Philadelphia 76ers vs. Chicago Bulls; Philadelphia, PA; 1991. © 2024 Nathaniel S. Butler.

Charles Barkley; Philadelphia 76ers vs. Chicago Bulls; Philadelphia, PA; 1991. © 2024 Nathaniel S. Butler.

Focus is an appropriate word choice. Butler has been tasked with framing seven-foot men with forty-inch vertical leaps moving at breakneck speeds in focus in his camera lens and knowing the precise moment to get the shot.

It’s an occupation he’s been training for since he was a child growing up in Montauk, out on Long Island. “It was just a little fishing community,” Butler says. “I was literally the only one that played basketball. I would travel around twenty miles to find a game.”

When he wasn’t playing hoops, he was working for his dad’s fishing business. Butler saved up his earnings to buy himself a Nikon FM2 when he was twelve years old. “Like someone would remember their first car, I remember my first camera,” Butler says.

For four decades Butler has captured the action on the basketball court inside the “World’s Most Famous Arena” on his camera.

He would fill his days going to school, searching for pickup basketball games, working for his dad, and snapping pictures of sunrises, sunsets, and fishing excursions. Thursdays were special. That’s when Butler would run to the mailbox to find his weekly Sports Illustrated magazine delivery. He would fill his nights tuning into New York Knicks games on the radio as he admired the photos torn from those pages, which he covered his bedroom walls with like posters. “It was the Walt “Clyde” Frazier era. The good Knicks teams of the ’70s. And like every kid had, I was in the driveway counting down ‘5, 4, 3, 2, 1,’ pretending I was Walt Frazier against Jerry West. And I loved Jerry West, so I was a little bit conflicted there. I wanted to play like Jerry West and be cool like Walt Frazier…I failed on both accounts,” Butler adds, with a self-deprecating laugh.

No, Butler might not have gone on to be known as “The Logo” like West or speak with dazzling diction like Frazier, but he succeeded in nurturing his passions and creating a path so he could keep basketball and photography as foundational pieces throughout his life.

After high school, he enrolled at St. John’s University. While Butler had a solid high school hoops career, he knew his limitations when it came to competing with the best in the Big East. “We’re talking Chris Mullin, Mark Jackson, Walter Berry,” Butler says. “I was friends with those guys, hung out with them, but was not good enough to be on the team. So I started taking pictures.”

LeBron James and Paul George; Miami Heat vs. Indiana Pacers; Miami, FL; May 22, 2013. © 2024 Nathaniel S. Butler.

LeBron James and Paul George; Miami Heat vs. Indiana Pacers; Miami, FL; May 22, 2013. © 2024 Nathaniel S. Butler.

St. John’s played their biggest battles at The Garden when behemoths like Georgetown, Villanova, and Syracuse came to town. Butler chronicled his school reaching the No. 1 national ranking, working nights and weekends as an apprentice for Sports Illustrated. While the magazine pages featuring the works of guys like Walter Iooss Jr., Manny Millan, and Heinz Kluetmeier were still tacked up in his bedroom back home, Butler was now working side by side with those photographers. “It was an invaluable experience learning from those masters,” Butler recalls. “I just felt comfortable in that world. I would assist those guys and help them at the crazy, big events they were covering. And then I’d go back to St. John’s, shoot the game; develop my film; go to practice; shoot practices… over and over again, working on my craft. Just like lawyers don’t argue a case in front of the Supreme Court a year out of law school, photography is like any other profession that you have to develop and work at.”

While Butler was in his last semester at college, he started working for the National Basketball Association under longtime public relations guru Brian McIntyre. “It was an internship before internships were the industry standard,” Butler explains. “My office was three doors down from David Stern’s office. It was a unique time for the league. Former commissioner Larry O’Brien was on his way out. David was on his way in.”

Butler was assigned grunt work, but he found glory in it. “As part of my duties, David would have every NBA city’s newspaper delivered to the office, and I would go in at six o’clock in the morning and do clips from every newspaper,” Butler says. “The three papers in LA; three in New York. Denver. Chicago. I was fascinated by how the league was covered. I would read the stories, of course. Not just because that’s what Stern wanted a summation of, but because I was interested. But the real treat for me was looking at the photos accompanying the stories in the newspapers. There was excellent photography in the Los Angeles Times, the Chicago Tribune, the Washington Post…I was in heaven doing that.”

Anthony “Spud” Webb; Atlanta Hawks; NBA Slam Dunk Contest; Dallas, TX; February 8, 1986. © 2024 Nathaniel S. Butler.

Anthony “Spud” Webb; Atlanta Hawks; NBA Slam Dunk Contest; Dallas, TX; February 8, 1986. © 2024 Nathaniel S. Butler.

While the league now had a budding photographer as an intern in Butler, it did not have a photo department. NBA Entertainment had just started on the video side and would find great success with Michael Jordan’s Playground and Michael Jordan: Come Fly With Me VHS tapes, but there was no in-house still photography system. So Butler and another young shutterbug, Andrew D. Bernstein—known to his friends and colleagues as Andy—put their heads together. “I said, ‘I sort of need a job when the internship ends—why don’t we create a photo department for the NBA?’ As crazy as it sounds, that’s sort of how it all started,” Butler explains.

Bernstein, who was inducted into the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame in 2018 as a Curt Gowdy Media Award winner, would be based in Los Angeles and keeping tabs on the Lakers and Clippers. Butler got New York and the Knicks and The Garden, and later, Brooklyn and the Nets and Barclays Center. “It was a joy to help create NBA Photos with Nat back in the mid 1980s,” Bernstein says. “His vision and deep love for the game of basketball, plus his unmatched talent as a photographer, made us a great duo on both coasts.” Then, as the NBA evolved, going from tape-delayed playoff games being aired on television to prime-time appointment viewing, so did Butler’s execution. The beauty in building a department from the ground up was Butler had the freedom to experiment. “Lighting an arena like Madison Square Garden is not an easy undertaking, by any stretch,” Butler says. “But we had the supplemental lighting. And how the pictures look, that’s something I take great pride in. I went to great lengths. I couldn’t control the players. I couldn’t ask them to pose. But I could do certain things to get the lighting right. And along those lines, I worked and developed a remote system that is now considered pretty standard.”

Butler spent nearly two years fabricating a multi-camera remote triggering system and tinkering with how radio frequencies transmit in an arena. “It might work fine at two o’clock, and then when there are twenty thousand people in the arena at seven o’clock, it malfunctions,” Butler says. “Why? Well, the human body is made up of 60 percent water. It doesn’t work with water. And then you figure out that challenge, and time goes by, and the next hurdle is twenty thousand people on a cell phone frequency. It’s constantly evolving, and that’s one of the things that I enjoy. I enjoy the challenge, and while you’re not recreating the wheel, you are definitely always looking for improvements and little things to enhance the ultimate product.” As the NBA expanded its photo department with shooters in cities around the country, Butler took pride in seeing other photographers incorporating his innovations into their work—be it through his remote system or shooting high-quality strobe images with handheld cameras.

“Nat Butler has been doing this for a long time,” says Noah Graham, an NBA photographer based in the Bay Area. “He’s in the ‘legend’ space, as far as can I tell. And we all kind of watch as we are going through it—similar to the way basketball players watched Kobe, as photographers, we watch the generation in front of us. And he is a generational talent; he’s still doing incredible things, and we’ve all had his example to look at. It’s an honor to know him; it’s an honor to learn from him and call him a colleague.”

“When I got to meet Nat for the first time, he took me to a Nets game, and I sat with one of his Hasselblad remotes,” adds Joe Murphy, who started in the licensing arm of NBA Photography before becoming the team photographer for the Memphis Grizzlies. “Nat was above and beyond; he was one of the best guys to watch because you could tell the work ethic that he always had—it didn’t matter if it was Game 6 of the Finals or a Tuesday night game at The Garden against the Dallas Mavericks, he put in the same commitment each time. He put up the same type of remotes, and he provided the same type of coverage. I knew right away that this was the way to do a game. When I finally started with the Grizzlies, he was absolutely someone that I modeled myself after.”

Dennis Rodman and Charles Oakley; Chicago Bulls vs. New York Knicks; New York, NY; 1996. © 2024 Nathaniel S. Butler.

Dennis Rodman and Charles Oakley; Chicago Bulls vs. New York Knicks; New York, NY; 1996. © 2024 Nathaniel S. Butler.

After shooting thousands of games and millions of images, Butler has stayed sharp by embracing the technological advances over the years—shooting digital to satisfy the immediate need for NBA content—but never settling for the instant gratification of a beautiful photo being as beautiful as he is capable of capturing. “I’m frequently asked what my favorite photo that I’ve taken is,” Butler says. “And sure, there are different images that are a ‘favorite’ for a short period of time. But then I’m onto the next one. It’s a little bit obsessive in a way. You’re always searching for that next great moment, you know? That’s what I do. That’s what I love. I love the challenge of that.”

And while the aesthetic is always important to him, so is the history behind what he’s seeing. “We are there to document things,” Butler says. “And it’s an editorial type of documentation. Obviously, it’s a live sporting event. You’re not telling the player, ‘Oh, I missed that. Can you go do that again?’ We don’t touch up in Photoshop, either. Whatever we shoot, that’s what we get—the way it comes out of the camera. And there are ethical guidelines, too. Digitally, we don’t enhance it. We’re not using AI.”

Butler found himself seated courtside for history on June 18, 2013. It was Game 6 of the NBA Finals between the Miami Heat and San Antonio Spurs. The Spurs led 3–2 in the best-of-seven series. A win by San Antonio would not only mean a fifth ring for Tim Duncan and Gregg Popovich, but a second Finals loss in three years for LeBron James, Dwyane Wade, and Chris Bosh. Abject failure for “The Heatles.”

As the game dwindled down inside of 10 seconds remaining, with the Spurs holding a 3-point lead and arena workers crouched at the corners of the court, holding yellow rope to set up for the postgame trophy ceremony, Butler was responsible for making sure his camera captured the scene forever. “You have to stay calm,” Butler says. “You’re in the moment. You have to be prepared. They’re bringing the ropes up. In the back of your mind, you’re ready for Popovich hugging Tim Duncan over to the left of the frame, over by the bench, or something like that. But, at the same time, the game’s not over. And the game’s never over when you have LeBron, D-Wade, Chris Bosh, Ray Allen. They’re in the game. They’re fighting until the end.”

For Butler…there’s a deep appreciation that his camera has kept him close to the game.

James missed a 3-pointer with 11 seconds left. Bosh grabbed the offensive rebound with 9 seconds left, and his pass out to Allen changed everything. “That particular picture just fell into place because I know Ray Allen,” Butler says. “I know what he does. I see him when we’re setting up our cameras three hours before the game—I see Ray Allen working on his game. So the key play was Chris Bosh grabbing the rebound. Ray was not phased at all. He’s backpedaling, doing what he does. His shooting that, his making that, it was totally in character for me to see. That’s what he does. I’d seen it countless times in the quietude of an empty arena.”

Butler, anticipating the pass out to Allen, waited to take the photo. With 6.7 seconds left, with the ball just released from Allen’s fingertips from the right corner and a sea of Heat fans wearing white as the backdrop behind him, Butler got the shot. “Oftentimes in a regular season game, you’ll see a team panic down the stretch,” Butler says. “They take a bad shot, or someone would get that rebound and force something up. But the Heat kept it in their zones of professionalism. And I have to do the same. Now, that doesn’t guarantee you get the picture. Just like him getting in position and shooting the shot doesn’t guarantee he makes it. But you do your part. He’s going to hit that big shot. And I was fortunate enough to stay within my comfort zone and get that photo.”

A photo of the biggest game-tying shot in NBA Finals history.

“The historian in me feels compelled to point out that the shot didn’t win the game,” Butler says. “It just forced it into OT, where Miami prevailed.” Butler’s instincts prevailed, too: “I wasn’t shooting on a motor drive. I’m shooting a single frame, one shot, and you just have to stay within yourself and be patient. And just get that moment when it happens.”

Stephen Curry and LeBron James; Golden State Warriors vs. Cleveland Cavaliers; Game 2 of the NBA Finals; Oakland, CA; June 5, 2016. © 2024 Nathaniel S. Butler.

Stephen Curry and LeBron James; Golden State Warriors vs. Cleveland Cavaliers; Game 2 of the NBA Finals; Oakland, CA; June 5, 2016. © 2024 Nathaniel S. Butler.

The photos from those moments have padded Butler’s portfolio, one so thorough and expansive that it would be hard to tell the NBA’s story without it. “Nat’s legacy of photography is huge,” says former Knicks guard Jeremy Lin. “Photography has definitely solidified and cemented so many parts of basketball and NBA history. We’re very grateful to Nat.”

For Butler, who figures he would have found a way to spend his life around basketball as a video coordinator or an assistant coach, even if that timely internship working down the hall from David Stern never happened, there’s a deep appreciation that his camera has kept him close to the game. “Still today, after forty years, I get excited when I walk into an arena and hear the bouncing of balls, squeaking of sneakers, and roaring of crowds,” Butler says. “For the past four decades, I have had a courtside seat to some of the greatest moments in basketball history and have had the privilege of photographing some of the world’s greatest athletes. The marriage between basketball and photography has been an unbelievable joy for me. And it’s not something you start out saying, ‘Oh, I’m going do this for forty years.’ It just happens. You’re enjoying it. You’re fortunate enough to be doing something that you love. And the years do go by faster than we would all like. It is hard for me to conceptualize that it has, in fact, been forty years of me doing this.

“And it’s been quite a privilege.”

__________________________________

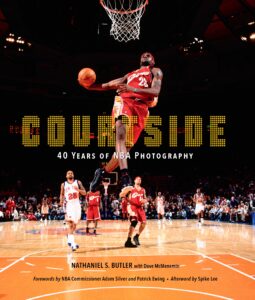

Excerpted from Courtside: 40 Years of NBA Photography by Nathaniel S. Butler. Published by Abrams Books. Copyright © 2024 Nathaniel S. Butler.

Dave McMenamin

Dave McMenamin is an NBA reporter, New York Times bestselling coauthor of Return of the King: LeBron James, the Cleveland Cavaliers, and the Greatest Comeback in NBA History, and contributor to several ESPN platforms, including ESPN.com, ESPN Radio, NBA Today, and SportsCenter. He is a three-time Professional Basketball Writers Association Blumenthal Memorial award winner and proud Syracuse University alumnus.