An Explorer Frozen in Time and a Map for the Mess of Life

Reid Mitenbuler on the Drive to Wanderlust and the Neuroticism of the Present

Foxe Basin, Canadian Arctic, Spring 1923

He was like the hero in an action movie: cool under pressure, always ready with a quip. In this particular moment, though, even he was nervous. He was lost in the Arctic wilderness, miles away from his basecamp, buried alive under the snow.

It had been foolhardy to leave the camp, all alone, to retrieve the supplies his traveling party had abandoned the day before. The supplies had been left because the sled dogs needed their burden eased in the heavy snow. But the group couldn’t afford to lose them permanently, so he’d headed back out as soon as possible. During expeditions like this, little delays accumulated into big delays that could disrupt everything—a risk he didn’t want to take, even though the weather was fifty-four degrees below zero, cold enough to turn spit hard as a pebble before it hit the ground. Besides, he was the kind of person whose mind was at peace only when his body was in motion. Sleep could wait.

He was sledding across the snowy expanse when he got caught in the sharp teeth of a sudden blizzard. Needing shelter, he created a makeshift igloo by digging a shallow depression in the snow and flipping his dogsled over it. Crawling inside, he covered the exit hole with a sealskin bag before grabbing a few winks of sleep. When he finally woke up, he was unsure how long he had slept. He tried to move the bag by kicking it, but it didn’t budge; the soft thud from his boot told him it was wedged there tight. Then he realized the blizzard must have pushed an unmovable mound of snow up against it. The space he now occupied wasn’t much larger than the interior of a coffin. The frozen walls pushed cold clouds of his damp breath back into his face.

I first encountered him in an oil painting, a bizarre rendering that looked like it was painted by a drunken sailor aboard a storm-tossed ship.

There was little chance, laughably small, that anyone would find him before he froze to death. Already his foot was succumbing to frostbite, a creeping numbness that would slowly take over the rest of his body. He thought about what all this meant—about her, about his children, about their reactions when they learned of his disappearance. He started thinking of ways he might escape. As the grim reality sank in, his heartbeat had the same erratic rhythm as a fish flopping in a net. He thought, “What a way to die.”

*

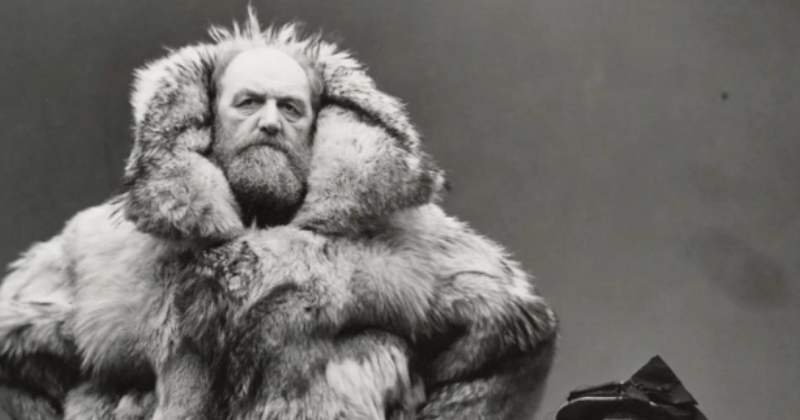

I first encountered him in an oil painting, a bizarre rendering that looked like it was painted by a drunken sailor aboard a storm-tossed ship—the brushwork was amateurish, the proportions clumsy, the perspective askew. But despite the awkward craftsmanship, the man in the portrait demanded my attention: he was impeccably dressed but sported a wild beard, a pirate’s peg leg, and had a mischievous, slightly amused expression. Everything about his appearance implied a good story, maybe even a fantastic story. When I approached the painting to get a closer look, I spotted the man’s name on a small brass plaque on the bottom of the frame: “Peter Freuchen” (pronounced “Froy-ken“).

The portrait was in an old mansion on New York’s Upper East Side, home to The Explorers Club, an organization founded in 1904, when large portions of the globe were still unmapped. The place was pungent with the atmosphere of a distant age: wood paneling, large fireplaces, leather club chairs, Persian rugs. It called to mind the stories of Rudyard Kipling or the set of a Wes Anderson movie.

One room had an old floor-standing globe, at least four feet in diameter, that I imagined a bygone generation of impressively whiskered men standing around while regaling each other with tales of the great voyages they’d once taken. I pictured them giving the globe a whirl, letting its spinning surface brush their fingertips as they reminisced. Once the spinning stopped, they probably poured themselves fresh drinks before settling in next to a warm fireplace, their rich growls competing to tell the evening’s best story.

My friend Josh had recently become a member of the club—its mission today is more focused on field study—and invited me to visit. He said we’d go after hours when the place was quiet and we could catch up over a couple of whiskies. He promised to show me around this bizarre old mansion that was still crammed with relics from the club’s faded past.

Dusk was descending when I got there, casting a pale glow through the windows. Clutching our drinks, Josh and I climbed a creaky staircase up to the Trophy Room, a space filled with old artifacts and hunting trophies that included the hide of a Siberian tiger rumored to have eaten 48 men. It took me a minute to finally notice the painting of Peter Freuchen, high above a stately brick fireplace.

I was intrigued by the image’s eccentricities, then started wondering what Freuchen had accomplished to get his portrait placed in such a proud setting. The Explorers Club has had many notable members—including Theodore Roosevelt, Thor Heyerdahl, John Glenn, Sir Edmund Hillary, and Roy Chapman Andrews, one of several indirect influences on the Indiana Jones movie character—so why Freuchen?

I recognized in him a cask-strength version of the wanderlust that, to some extent, drives all of us.

I decided to research his past. The story that unfolded was a sprawling tale of adventure set against the uneasy backdrop of the twentieth century, as the world’s ordered assumptions tilted precariously in the face of disruptive forces. The most volatile parts of this era—political, economic, and cultural—seem to collapse themselves to the scale of Freuchen’s life, a collection of random beats that somehow find a rhythm together.

His journey wanders through the Arctic, the jungles of South America, Golden Age Hollywood, the Soviet Union, the White House, Nazi Germany, the American Civil Rights Movement, a good many bedrooms, and a legendary television game show. Along the way, Freuchen encounters a name-dropper’s paradise of eclectic personalities—politicians, writers, artists, journalists, spies—and he surprises us with his early warnings about climate change (before anyone called it that) and his proximity to a pioneering series of experiments in psychic perception. There is something of a “Where’s Waldo?” aspect to Freuchen: a man wandering the world, unexpectedly popping up in random places and guest-starring in history’s big moments.

Freuchen’s life was full of adventure and suspense, but the part I find most intriguing was his embrace of the terror, grace, wonder, and weirdness that compose the full spectrum of human experience—and life’s inherent messiness. Men of Freuchen’s demographic—swashbuckling explorer types—might not be as fashionable as they once were, and his tale might fluster a few contemporary readers, but it’s the very messiness of his story that is most valuable, especially when considered within the proper historical context.

Like all of us, Freuchen was flawed—no interesting person isn’t—but he ultimately managed to find himself “on the right side of history” by defending underdogs and championing tolerance, empathy, and environmental stewardship. His tale has the rare ability to remind us that history, so often seen as the source of our discontents, can sometimes reveal their remedies too. It calls to mind a quote by the writer Julian Barnes: “What is it about the present that makes it so eager to judge the past? There is always a neuroticism to the present, which believes itself superior to the past but can’t quite get over a nagging anxiety that it might not be.”

One more thing drew me to Freuchen’s story, a quality I think many others will appreciate. I recognized in him a cask-strength version of the wanderlust that, to some extent, drives all of us. He was the consummate searcher, never fully satisfied with how things are, but always wondering how they could be instead. This urge took him to dangerous places, where he was forced to grapple with his own vulnerabilities, disappointment, and loss—and he became a stronger person for it. What I take from Freuchen’s story, and what makes it most redeeming, is not necessarily the bravado of his adventures but the optimism that drove them, the belief that we can always do better.

_______________________________________

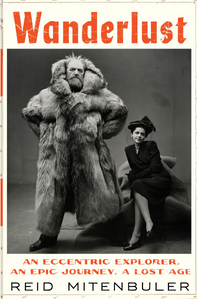

From WANDERLUST by Reid Mitenbuler. Copyright © 2023 by Reid Mitenbuler. From Mariner Books, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers. Reprinted by permission.

reidmitenbuler

Reid Mitenbuler is the author of Wanderlust: An Eccentric Explorer, an Epic Journey, a Lost Age, Bourbon Empire: The Past and Future of America’s Whiskey, and Wild Minds: The Artists and Rivalries That Inspired the Golden Age of Animation. His writing has appeared in The Atlantic, Slate, Saveur, The Daily Beast, and Whisky Advocate, among other publications.