An Excerpt from Mondegreen, a New Novel of Wartime Ukraine

Read New Writing from Volodymyr Rafeyenko

Editor’s note: Given the ongoing war in Ukraine, Literary Hub is amplifying its coverage of Ukrainian writers this month. The following is an excerpt from Volodymyr Rafeyenko’s Mondegreen: Songs about Death and Love, which “tells the story of Haba Habinsky, a refugee from Ukraine’s Donbas region, who has escaped to the capital city of Kyiv at the onset of the Ukrainian-Russian war,” according to the book’s publisher.

*

What could be the essence of all of this, O master? Haba breathed in the frigid Kyiv air and pondered how this year’s autumn had been so warm and yet the cold came so quickly, seemingly out of nowhere, and how this was a real mind-fuck. Well what then could be the essence of all of this? And what is the Ukrainian essence, if you compare it with, say, the Russian one? Of course, the Ukrainian essence, if it is our national one, should be different from the essential essence, so to say, of the enemy? Right? Or are there certain philosophical coordinates where the national disappears and the essentially human sets out upon its difficult and senseless path? Can we suppose that Russians are inhuman? That Ukrainians, for example, are humans while Russians are—the reverse (the re-verse—what a wonderful word; re-creation? A time of reproduction? And Jesus said to them, “Truly, I say to you, when the Son of Man will sit on his glorious throne, you who have followed me in the re-creation will also sit on twelve thrones, judging the twelve tribes of Israel).1 And if we are to accept this, well then how about the French or, more generally, the Europeans? How do you co-exist with them? All those Sartres, Camus, and Levis—what are they, biologically speaking? Deleuze, Derrida, Barthes. And Darwin in particular (Charles Robert Darwin)? And where the hell did this curious theologian come from? And couldn’t some virtuous person have showed up and bashed his bones with a baseball bat to stop him from writing that idiocy of his about people and monkeys having common relatives? Well tell me this, Mr. Theologian. Do you get a kick out of a monkey and wise men having common relatives?

Of course not, it’s all very clear. Homo sapiens—or, as it is proper to say now, Homo sapiens sapiens—with all your sadness and intoxication, well, who haven’t you slept with, you loser, especially in those knotty 1990s. And what then can be said about the 2000s and 2010s, which were filled to the rim with fire.

You know, sometimes things line up in such a way that it becomes unbearable. The soul gets torn by a sense that life is expiring and pulling away from you, like the nighttime local train to Publiieve-Neronove (the same as Klavdiieve-Tarasove, a small town in the Borodiansk district of Kyiv oblast. Founded in 1903, located 1,440.71 miles from Paris. At the fork, stay to the right and continue on A4/E25/E50; follow the signs toward Paris/Luxembourg/Thionville), which flickers its phantom fires. And, moreover, a spiritual development doesn’t come at all. You look back into past days and they are empty, and instead of a greater awareness ringing in the radiance of a fullness of existence, you are left with the bland, concrete slice of cake of a provincial railway platform. Empty packs of cigarettes, sunflower seed shells, a half-empty bottle of Chernihiv Light beer, a homeless dude on a bench reading Conan Doyle. The wind spreads yellow dust. And, standing up to your ears in that dust, you come to understand that you haven’t done anything worthy in your life (existence is bleeding to death, looking into you with the sad eyes of dead relatives and folk tale characters).

And it is in that state that sapiens sapiens drifts through the woods. In that state. And there’s a monkey sleeping there. Can you believe it, dear compatriots? This guy is preoccupied with existence, while the monkey just fucking sleeps. This guy’s sadness has got him by the balls, while the monkey, drunk off champagne, lies beneath the walnut tree. The bodhisattvas of Ukraine. Each in its own manner, of course. And that is where relatives come from.

It would be better for this Darwin to ask whom his mother slept with. This theologian. Why is he picking on monkeys? There are so many animals in our society that that spiel about monkeys—it’s not even half the truth. It’s only a quarter of the problem. I wonder why he didn’t write anything about those wild boars, crows, hedgehogs, rats, butterflies, dragonflies, dogs and wolves, bears, snakes, laughing and crying hyenas, and just a few innocent woodpeckers, that make up our political scene? It’s a real frog-fest, this parliament.

“But why is it Darwin that I am attacking?” Haba suddenly wondered.

Why not Martin Luther? And the fact that he’s German doesn’t mean anything. Germans, actually, are the same way, except that they are fonder of order. If you should break some sort of law, like, for example, deciding to take a leak in the middle of the Brandenburg Gate, then your friend-bursche, with whom you had just been downing beers in a bar, will turn you in to the police, you can be sure of that. Even if you were a proponent of, say, anarcho-radicalism.

“So then, what is all this leading to?”

Well, who knows, master, what this is all leading to, Haba shrugged his shoulders, but I am learning a language. A language so musical and magical. One that leads you to all kinds of nonsense and multicolored idiocy, it calls you to March madness, to holy hollow November. You can mumble non-stop about anything in this language for a hundred thousand years, and speak gobbledygook with your tangled, refugee tongue. (Gobelen? Gusk? Let’s home in on that rabbit and his balls).

And it is at this moment that Haba thought that, perhaps, he is beginning to develop a polyglot syndrome. While talking to himself only in his native Russian, he remained an average Joe. But when he began learning a second language, all sorts of God-knows-what began entering his brain. From much knowledge, there is much despair.

“That is the fate of today’s intellectuals,” he said to himself, sighed heavily, and, with a dawdling sadness, breathed the lively air of perpetual expulsion into his greying beard, made the sign of the cross, and continued strolling down Obolon Avenue.

Well, what the heck can you do, it’s autumn. Autumn. And what is autumn? It is the onset of a turning point. The sky cries in blood beneath your feet. And stupid crows scuttle through the puddles. Kyivan crows, fucking eh. “So then,” Haba mumbled, “why the hell didn’t you, Mr. Pushkin, tell us anything? You were a pretty decent chap. And talented. If you saw a Jew, you would say to him: look at the Jew. If you saw a babe, then you’d say: ababahalamaha. And then you’d grab her by her skirt. Come here, sugar. He brought her to his corner, wrung his hands, sat her tied-up on a stool and said to her in perfect German: I am your Sacher-Masoch, mein daaarling. I brought you to the City of the Lion itself. I’ll start telling your tales, calling you pannochka, you’ll be a sexually satisfied chick. You’ll become a true halychanka. But she says to him: go fuck yourself, you perverted horse, damn you! I ain’t no halychanka, I’m the French novelist and playwright Honoré de Balzac. The novel sequence La Comédie humaine, which presents a panorama of postNapoleonic French life, is generally viewed as my magnum opus. And I have such long, curly hair, because I curl it on giant nails forged in a metallurgic guild, and that’s how I sleep, after drinking Marsala and smoking weed. I wake up in the morning looking flawlessly beautiful.

And I could share this good fortune with you.

__________________________________

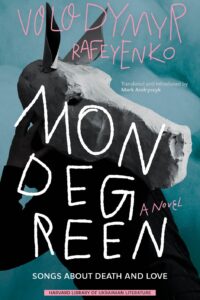

Mondegreen: Songs about Death and Love by Volodymyr Rafeyenko, translated by Mark Andryczyk, is available via Harvard Ukrainian Research Institute.

Volodymyr Rafeyenko

Award-winning Ukrainian writer, poet, translator, literary and film critic. Having graduated from the Donetsk University with a degree in Russian philology and culture studies, he wrote and published entirely in Russian. Following the outbreak of the Russian aggression in Ukraine’s east, Rafeyenko left Donetsk and moved to a town near Kyiv where he wrote Mondegreen: Songs about Death and Love, his first novel in the Ukrainian language, which was shortlisted for the Taras Shevchenko National Prize, Ukraine’s highest award in arts and culture. Among other recognitions, he is the winner of the Volodymyr Korolenko Prize for the novel Brief Farewell Book (1999) and the Visegrad Eastern Partnership Literary Award for the novel The Length of Days (2017).