An Endless Summer of the Best in Surf Lit

From Dark Surf Noir to the Zen of the Waves

I grew up in an old fishing village in Massachusetts, which is nothing to complain about, I know, but the water there was so goddamn still it could drive you crazy. The beaches were protected from the North Atlantic by two hundred square miles of bay, twenty islands, a few thousand islets and ledges, and a dredged harbor with a controlling depth of fourteen feet. A rough day meant the waves broke over your shins instead of your ankles. As a teenager I began to read surf books. I couldn’t imagine a world without saltwater, but that water ought to have some life to it, I thought, and I didn’t want to hear about scallops and steamers. I wanted a storm-born swell that rolled for a thousand miles and broke over coral, and I wanted to see somebody, preferably a Hawaiian, ride the thing like he was taking communion. It didn’t seem like too much to ask, but for several years I was stuck with the bay, so I kept a library card handy and took my books to an empty stretch of beach where I could look up from the pages now and again and pretend what I was seeing was a quiet day at Banzai, or some undiscovered paradise off the coast of West Sumatra.

Come summer, the old habit tends to resurface. The sport—or better to say, the culture—produces a formidable volume of writing, so I’m hardly ever at a loss, and there are always the classics to revisit. Surfing lends itself well to literature. There are flashes of blood-pumping action, followed by long stretches of waiting, during which time a lot of thinking can be done, about the nature of life and the elements, if that’s your bend, or about the real estate developer who wants to buy your beloved coastline, or about the crime you’re trying to solve, usually because a girl has gone missing after getting involved with drugs or gangsters or real estate developers.

For the new season, here’s a list of books to alter your outlook and transport you to a break off some sunny coast, or to a sleazy surf town overrun with hustlers and pilgrims. Pick one up for your vacation, or if you’re going to a New England bay, pick up three or four to get you through the lovely days and those long, tranquil nights.

SURFING IN FICTION

Tapping the Source, Kem Nunn

Tapping the Source is at the head of nearly everyone’s surf canon, and with good reason. Kem Nunn’s debut novel, which was a 1984 National Book Award finalist, has dominated the genre for over thirty years. Set in Huntington Beach, the seedy heartland of California surfing, Tapping the Source is about the corruption of an ideal. There is the surfing, and then there’s everything around the surfing. Nunn’s world is populated by beach bums, gearheads, shell-shocked vets, sellouts, teenage runaways, South Pacific gangsters, porn tycoons, and suits, all of them hell bent on indulging a few vices, principally drugs, sex and money. The plotline here is pitch black: a sister goes missing in Huntington Beach; her brother leaves their inland desert home to search for her; he uncovers unspeakable acts, then commits a few of his own. There’s nothing glamorous about Nunn’s SoCal, but there is something intoxicating about it, and once you’ve had a taste, you can’t help but want more.

Fortunately…

The Dogs of Winter and Tijuana Straits, Kem Nunn

Along with Tapping the Source, these two novels round out Nunn’s seminal “surf noir” triumvirate. Both are set at the extremes of California, The Dogs of Winter in the northern reaches of the state, and Tijuana Straits in the desert-meets-sea southern borderlands. This is rugged, hard-fought territory, and the locals tend to be suspicious of, or downright hostile to outsiders. (Barbarians at the gate—or inside the gate as the case may be—is an important theme in surf literature. There are only so many good breaks; aficionados work hard to keep them under wraps.)

Like Tapping the Source, the later Nunn novels bring “crime” elements to the table—murder, treachery, investigations, of one form or another. But in true noir fashion, solving the mystery doesn’t right much of anything; it only proves the world is a barren, unforgiving place, with only the faintest line separating violence and bliss.

(If, after these three novels, you find you still haven’t had enough Kem Nunn, try out the short-lived HBO series, John from Cincinnati, co-created by Nunn and David Milch. That’s right, a decade later, let me be the first to give that show a ringing endorsement. Okay, not ringing, but still, it’s ambitious and strange and better than many of today’s prestige dramas. It also had the best opening credits in TV history.)

Breath, Tim Winton

Winton’s coming-of-age story is about two boys, ages 12 and 13, learning to surf under the tutelage of a mysterious, brooding figure named Sando. The thing about 12- and 13-year-old boys that isn’t often explored in literature, but which Winton captures so well, is this: they don’t care whether they live or die. Recklessness is often what bonds friends at that age, and once it’s gone—once fear or maturity sets in—it’s gone forever, and oftentimes the friendship follows suit. Winton renders this period of discovery and distancing beautifully. His language is precise and evocative and wistful in perfect measure, and the rugged sea- and landscapes of Western Australia have rarely, if ever, been captured so vividly.

Dawn Patrol and The Gentlemen’s Hour, Don Winslow

Don Winslow is known for his DEA and drug cartel sagas—Savages, The Power of the Dog, and last year’s bestselling Cartel (with a new installment in the series coming soon)—but in certain circles, his best loved character is Boone Daniels, who rides the waves of Pacific Beach by dawn and by night scrapes together a living as a PI. Daniels is a classic noir hero: an errant knight reluctantly making his way through a sordid, greed-driven world. This being San Diego, the trouble he gets into usually involves drugs, condo developers, racial tension, or all three at the same time. What really sets the series apart from other detective novels (in addition to the surfing) is Winslow’s deep knowledge of the social forces at work, which allows him to pull back from the intimate character details—the personal codes, the riding styles, the post-session breakfasts—in order to indict the vast and ugly machinery of modern crime in California. Winslow has something of the 19th-century novelist in him, a scope he brings to bear whether he’s writing about drug lords or surfside shamuses.

SURFING IN NON-FICTION

Barbarian Days, William Finnegan

Finnegan’s Pulitzer Prize-winning memoir is the new gold standard for surf literature. The book came out just last summer, but its stories have already entered the culture’s lore: “Doc” Renneker and San Francisco’s underground scene; camping for months on an uninhabited island in Fiji and being among the first to ride the now famous Cloudbreak; Honolua Bay on acid; defying death on the giant Madeira waves. Finnegan’s prose is meticulous and elegant. He’s been a reporter for most of his life (on staff at the New Yorker, writing about world politics since the 1980s), so you can be sure that he had a notebook along for the adventures relayed in Barbarian Days. The details shine through: the smell of the sea at an obscure break, the morning wind in Ocean Beach, the inside of a barrel surfed thirty years before. Barbarian Days has to be approached with some caution, though. It’s not a book to read if you’re feeling unsettled or dissatisfied with the state of your life, because inevitably you’ll hold yours up against Finnegan’s and feel a little inadequate. But if you’re in the mood for the memoir of a life well lived, and well considered, you won’t find a more insightful recollection anywhere.

Welcome to Paradise, Now Go to Hell, Chas Smith

Chas Smith, a former war reporter turned surf scribe, is a big character, reviled by some in the surf world. He refers to his writing style as Trash Prose and dares his readers to recoil. But beneath the posturing is a keen observer of sub-culture, personality and economics. In Welcome to Paradise, he takes on Hawaii’s North Shore in the winter months, when the big waves and the big money come in. Smith is immersed in the community. He has a flare for dramatics, too, and is capable of capturing scenes with startling vividness: “Chicken and dog and teriyaki sauce and salt water and rot and surf wax. The women with chipped toenail polish and hungry eyes… Mobs of surfers high on adrenaline and cocaine. Surf industry scenesters running scared and also high on cocaine and also chasing the women. The waves.”

Becoming Westerly, Jamie Brisick

Surf literature is probably not the first place you’d think to go for a complex study of human sexuality, gender norms and identity, but that’s what author Jamie Brisick found when he met Westerly Windina, a platinum blonde lawyer and aspiring actress, formerly known as Peter Drouyn, the Australian surfing champion. Drouyn was a surf icon and a well-known playboy during a particularly testosterone-soaked period in surf history, but later in life, he found himself discontent, and shifting from one path to another, until a bad wipeout awoke him to the truth: that Peter was gone and Westerly was born. Becoming Westerly begins with Brisick and Windina on a plane to Bangkok, where Windina’s gender reassignment surgery is performed. Brisick later talks with the greats of the Australian surfing scene, some who believe Westerly is another of Drouyn’s famous performances, and others who see in her transformation a natural extension of the sport’s spirituality, and its inquisitive core. Becoming Westerly also explores what it means for Windina to surf as her true self, when she no longer attacks the waves or seeks solace there, but instead finds peace.

The Wave, Susan Casey

Susan Casey’s first subject is the wave itself, but not just any wave. She’s after the giants, topping out at over 100 feet, a size and strength that science believed impossible, until they were observed. The Wave begins on an oceanographic journey in the North Atlantic. But while Casey’s mind is with the scientists studying these rogue waves (and the havoc they wreak on coastal communities, as climate change intensifies their strength and frequency), her heart is with the men who travel the world in hopes of surfing them. Laird Hamilton, the godfather of tow-in (in which surfers get dragged by rope and jet-ski, since the waves are moving too fast for arm paddling) is Casey’s best muse, and if you’ve never spent an afternoon scouring YouTube for videos of Hamilton at his craft, do yourself a favor and try it out today. Big wave surfing is the height of human boldness, or insanity, depending on your view, and Casey fully embraces the challenge of capturing that spirit on the page.

Saltwater Buddha, Jaimal Yogis

Saltwater Buddha is several different memoirs combined into one: a coming-of-age story about a rebellious kid; an expedition report; a spiritual awakening. Yogis was a teenage runaway who turned up in Hawaii and fell in love with surfing, then chased waves around the world. He was also a “new age” kid who took off with a copy of Hesse’s Siddhartha in his back pocket and followed the path of the Buddha by paddling out on a surfboard. It sounds like a book likely to fall prey to the surfer-philosopher clichés, except that Yogis is such an assured, matter-of-fact storyteller. His tale is about overcoming ego, and reading Saltwater Buddha, you can’t help but believe that’s he’s managed it to an impressive degree. Yes, the waves are big and the rides are epic, but Yogis writes with a sereneness that suggests something deeper at play. And anyway what kind of surf list wouldn’t have a touch of the Zen?

In Search of Captain Zero, Allan Weisbecker

Surfing culture is full of good yarns, mostly of the ‘you should have been here yesterday’ variety made famous in The Endless Summer, but when it comes to epic tales of high seas, violence, hidden paradises, and drug smuggling, Weisbecker is in a special class. In Captain Zero, he sells off his worldly possessions, loads up the car (nicknamed La Casita Viajera), and heads down to Central America in search of his old surf-and-smuggling partner, Patrick, who fell off the map after sending a cryptic postcard years before, signed “Capitán Cero.” Weisbecker’s writing sometimes tends toward Hunter S. Thompson-style self-mythologizing, but that’s part of the fun with a memoir like this. There are quieter moments, too—meditations on friendship, wanderlust, aging and the workaday world—but Weisbecker is at his best navigating and narrating the close scrapes of a life of extremes and adventures.

A FEW EXTRAS

The History of Surfing and The Encyclopedia of Surfing, Matt Warshaw

Warshaw’s books are the most learned, engrossing, attractive guides you could hope to find. The man is obsessed, and also, luckily enough, immensely skilled. He’s a giant in the world of surf writing and history. If you’re starting a collection, start here.

Surf Craft, Richard Kenvin

If you’re into design, or just a gear fetishist, this is one to own.

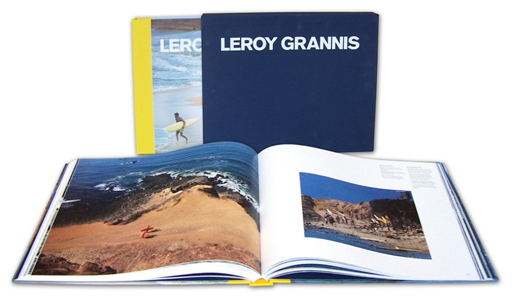

LeRoy Grannis: Surf Photography of the 1960s and 1970s

This is a gorgeous Taschen book, worth ogling whenever you get the chance.

Dwyer Murphy

Dwyer Murphy's new book is The House on Buzzards Bay, available June 24, 2025 from Viking Books. He is the author of An Honest Living and The Stolen Coast, both of which were New York Times Editors’ Choice selections. He is the editor in chief of Literary Hub‘s CrimeReads vertical