They say that walking is controlled falling, they say put one foot in front of the other, they say things will return to normal and you will adjust to the change, as if those are similar promises, and possible. They give you special equipment if you are deemed worthy of it, and if not, they assure you that you have special talents for adaptation. They call you resilient. If I am repeating what they say rather than what I think of what they say, it’s because—not being resilient—I struggle with every step.

This morning, Tala showed me how she can cross the room without even stumbling. I am ashamed to say she did this while carrying hot tea; her unoccupied arm was extended, undulating like the needle of some sensitive atmospheric dial. Elegant. “You only need one arm free to balance,” she trilled, daring to turn her head around and smile at me as she closed in on the room’s far wall. The smallest bit of amber tea sloshed from her cup then.

Tala is younger than me, by at least fifteen years (I can never recall her age: she is wise beyond it). Generally speaking, the younger are more resilient, of course.

*

She’s gone out again, and I’m alone.

She goes out more and more now, leaving me to my teas and infusions, my stained carpet, my small view out the glass back door. Through it, from this scavenged daybed, I catch sight of the concrete square that was a patio, now fractured into jagged, unwalkable terrain. Squirrels darting around. The leftmost edge of the fruitless pawpaw tree. Our two bicycles, entangled and fallen, their tires flaccid, dusted with debris. The chain-link fence threaded with dull-green ivy, and above it: a sliver of sky, sliver of a downtown skyscraper sheathed in mirrors, reflecting more sky.

Do you ever really look at the sky, really look at it for long enough to let your mind wander away and then wander all the way back—back to the looking, and then further back to noticing what it is you’re looking at, and how the sky is not a thing to be looked at, how the sky is not even a thing at all?

*

I want what Tala has. I’m not embarrassed to say it. I want her bony ankles and her wedge-heeled boots. I want the skin of her smooth forehead—dewy, there’s no other word—and I want her dates and her friends. I want that high-pitched laugh that peals, even when there isn’t much to laugh about. I don’t care that it sounds fake sometimes, I don’t care if it’s a mask or a manipulation, if she’s crying inside. It makes anyone who hears it happy: I want that.

(“Do you want her, or do you want to be her?” a person I once knew wrote in a book, quoting their therapist. It has never occurred to me to ask if I want Tala in that way. She wouldn’t have me, for one, and I don’t like rejection. Sometimes I wonder if she’s ever really looked at me at all.)

Wonder implies curiosity, implies delight. But it’s also code for doubt—for unprocessed, perilous doubt, from which its whimsy can protect.

I protect myself, by which I mean I defend myself. And I have known for some time that the only way to get what I want from Tala is to kill her.

* * *

I consult my list. I try to keep it brief; I keep having to rewrite it to make sure the priorities make sense, that the priorities on the list match the priorities in my head. I don’t like the feeling I get when they don’t. What’s it called? Cognitive dissonance. I never know what that means, really. You learn to mimic the language that gets you through the door. Gets you through the door is another example. Who taught that junk metaphor to me?

Door to what.

The list is in the kitchenette, on a strip of wall I painted with matte black paint so I can write on it with chalk. Faded white numbers, one through seven, line the left edge of the tall black rectangle; when I erase the list to rewrite it, I leave the numbers there. Out of laziness. Out of superstition. Lucky seven.

The list’s daily revisions, if I had recorded them somehow, would make a good diary. An archive, open to interpretation.

Today’s entry:

1. Coffee

2. Exercises—upper arms, back

3. Notebooks

4. Soak beans—flageolet (add kombu)

5. Balance

6. Calls—Insurance, C.

7. Lay groundwork

I can’t, of course, put “Murder Tala” on the list. She would see it: it’s right there in the kitchen we share, every morning and most nights, if I wait up for her. We sit around the red Formica table and watch wax drip from the candles I can’t help but light at sundown, a little ritual for timekeeping, a stand-in for ritual. The thick drips pool into white amoebas on the red surface; sometimes we read them together, our futures or our pasts. At some point we’ll run out of candles, I know.

“It’s a speech bubble,” Tala decided one night not long ago, frowning at a wax amoeba. “In your future. It means you haven’t yet learned to say what you really mean.” When she frowned, two small curves appeared above the corners of her mouth. Parentheses, in a delicate sans-serif font. Tala knows me, uncannily. It’s true, I’m not ready to be rid of her just yet.

What I don’t put on the list is what I spend most of my time actually doing. If thinking can be said to be doing, if planning can.

What would be the inverse of planning to kill Tala? Planning to let her live?

The more I stall—the more I leave off of the list—the more I wonder if I’m still moving properly in the direction of the future.

I once read a book whose protagonist’s life project was to dig a hole. Then I had a dog whose life project was to dig a hole: the coincidence made me better understand the book. The dog is dead now and I gave the book away, but it left a lasting impression, as they say. (What kind of impression does not last?)

What I mean is that reading and witnessing are not the same thing. Let alone doing.

What I spend most of my life doing is, in a word, regretting. I was once like Tala. I crawled out from wherever they placed me (“they,” for lack of a better)—I crawled out, hoping that something or someone would let me touch them, breathe on them.

I crawled out hoping, which it turns out looks a lot like dancing.

You should have seen me.

*

Tala goes dancing most nights, and I have asked her how they manage on the dance floor now, with all the aftershocks or whatever these movements are, these movements that convulse the ground beneath us, that almost never stop, not completely, so that now motion, rather than stillness, has become the rule. Stillness the exception that proves it.

Is it possible to imagine someone dancing in a way you can’t, yourself, dance? When I imagine Tala dancing, I imagine her moving the way I once did, in slow, precise response to the music, secret-smiled and low-lidded, a sway that begins with an invisible inner impulse and pulses out from there, always in relation to another body or bodies—I mean to specific, countable bodies, whether acknowledged or not. Sometimes I would move so slightly, you might not call it moving at all. No, I don’t imagine Tala dancing in the myriad unappealing ways I’ve seen others her age, at cast parties and in films, or on occasion at a club, dance—the hopping up and down as part of a throng, or the memorized friend-group choreographed bits, or the hypersexed flaunts à deux. I picture her familiarly, phenomenologically: a picturing from within. But I have no idea how Tala dances, how could I?

When I ask her how they manage she doesn’t answer—doesn’t even acknowledge the question. She just lets out that peal of laughter, throws back that lovely head.

__________________________________

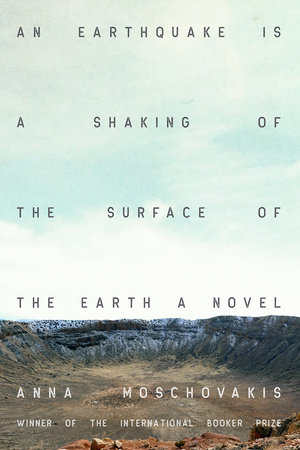

From An Earthquake Is a Shaking of the Surface of the Earth by Anna Moschovakis. Reprinted by permission of Soft Skull Press. Copyright © 2024 by Anna Moschovakis.