An American Experiment: Jeff Boyd on Race, Music, Religion, and Love in Contemporary Portland

In Conversation with Whitney Terrell and V.V. Ganeshananthan on Fiction/Non/Fiction

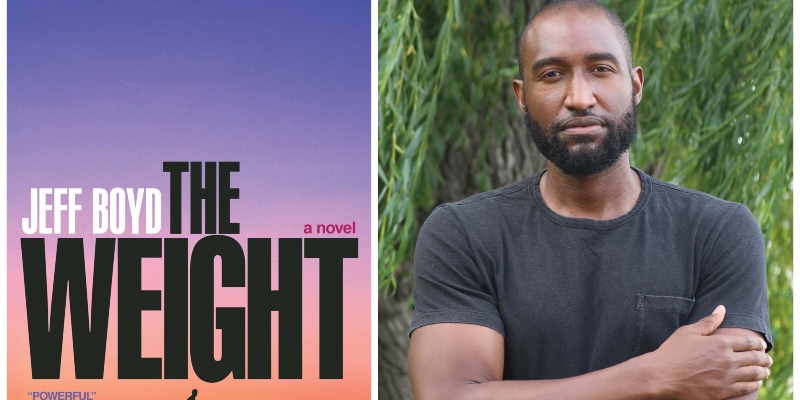

Fiction writer Jeff Boyd joins co-hosts V.V. Ganeshananthan and Whitney Terrell to discuss his debut novel, The Weight, a coming-of-age story about a young Black musician who struggles with romance, religion, and racism in predominantly white Portland.

Boyd talks about his personal struggles with and admiration of faith, the difficulties of developing an identity, and his own experiences as a Black man living in Oregon. He reflects on the dynamics of bands, as well as his protagonist’s romantic relationships and ability to forgive. He reads an excerpt from the book.

Check out video excerpts from our interviews at Lit Hub’s Virtual Book Channel, Fiction/Non/Fiction’s YouTube Channel, and our website. This episode of the podcast was produced by Rachel Layton and Anne Kniggendorf.

*

From the episode:

Whitney Terrell: [Your character] Julian has a complicated relationship to Portland, Oregon. He calls the neighborhood that he’s in “a refuge from all things evil and hard,” which seems nice. At the same time, he says, “everywhere I went, I was the Black guy.” So what’s it like for a character to live in a neighborhood they love, but at the same time, feel like they don’t belong?

Jeff Boyd: Yeah, I think that complicated things for him. I think it also is why he stays no matter what happens. He’s like, well, this place is great. On a daily basis, there’s things that he appreciates about it: He has friends that he appreciates; he has like-minded people in that sense. He’s not removed from the world, or from American culture, but when I’ve had that, even living in Portland—I did live there—it’s like, oh, my white friends. Now just imagine: all of a sudden, snap your fingers, everyone around you is Black. Like, just visually, you can’t escape it.

Julian doesn’t even want to think about being the only Black person around. It’s just natural for a human being—you’re going to notice that no one is like you. It’s like when you’re trying to play a game with a kid. One of these things is not like the other. Your mind is going to get drawn to that, at least sometimes. And when that does happen, it’s hard for it not to be like, well, why is it this way? Since I’m not like everyone else, should I be here?

There’s this unnatural feeling that comes in, if you’re having a nice serene time, someone at some point is gonna open his eyes and look around the room and think, “Oh, man, I’m the only Black guy here.” That changes the way you feel, like you can let your guard down and almost immediately, it makes you put your guard back up. Just because it means it’s survival, I think.

V.V. Ganeshananthan: As I was reading, I was thinking about AWP in Portland, which was maybe the last time I was there. And I was like, “Oh, I’m so excited to be here in this progressive place with all of its natural beauty,” and… exactly what you’re describing. We needed the question that you asked: “What is it like for a character to live in a neighborhood they love but where they feel like they don’t belong?” I feel like it could just as easily be—I’m in Minneapolis—and it just seems like it could also be a very Minnesotan question. It’s something that you portray really beautifully.

WT: There’s also this really wonderful subplot with Claire and Peter, who are the neighbors who live across the street and have an adopted son who was Black named Reggie. And so they, of course, immediately approach Julian, and he thinks that they want to be friends at first, but really they just want him to hang out with their kid because he’s the other Black guy that they know. And their relationship is complicated.

They do things that hurt his feelings, but they also grow and change with him. And I thought that was one of the interesting things about the novel—the way that Julian negotiates complicated relationships. One single incident or case of misunderstanding doesn’t end his relationship with people. He tends to work through that.

JB: Yeah, I think it also ties back to the faith thing. You know, he doesn’t say it explicitly in the book, but my idea is that he feels that only God can judge. You know, he’s not in the business of judging people, for better or worse, and I think sometimes that gets him in trouble. And sometimes it helps him.

I think that that’s related to this relationship that he has with them. He can see, “I guess if I had a Black kid, and I was living in this neighborhood, and everyone else around me was white, I might feel like maybe my kids should get to know some other people who look similar. So it doesn’t feel like he’s the only Black person here.”

I think Julian gets that to an extent. He does feel hurt by the fact that it doesn’t feel like a genuine relationship. At first, it feels like people want something from him and don’t want to give him anything back. He does feel hurt by that. But he also sees that Reggie—who’s adopted and 13 or 14 years old in the book—that Reggie can use his guidance. And I think Julian can also get something from Reggie. He doesn’t have to feel alone when the two of them are playing basketball or, for instance, they can feel there’s still these two Black guys there in this world, but they’re not alone.

I think it also happens with Claire and Peter. They join and they both start to influence each other in ways that help them see the bias that they hold. I think that it’s related to Portland where a lot of people are liberal and well meaning, but don’t think they have to practice what that means theoretically.

This book takes place before the Black Lives Matter movement, but a few years after this, Julian’s gonna walk around the street, and they’re gonna have a lot of Black Lives Matter signs on either side. And he’s gonna say, “So you’re telling me I matter, thank you.” Because there’s no one else to read it like that. It’s different than that. Also, we have Claire and Peter, who do have these well-meaning intentions for their son and for the world. They never had to practice this, so being out of practice, you see bumps along the way.

VVG: Did you start writing this book while you lived in Portland? Or was it something that you had to begin with a little bit of distance?

JB: Yeah, I definitely started it almost as soon as I moved to Chicago. I moved back to Chicago, and I was like, here we go, what can I write about?

WT: I feel what you’re describing there—I’ve written about Kansas City’s neighborhoods, and it has a lot of racial segregation. I would jog or ride my bike through what I know to be a very, very white neighborhood and you see all the Black Lives Matter signs. You’re like, who are they saying that to? Me? I guess each other?

JB: Yeah. In rural Oregon, or rural Minnesota, for instance, that’s a real statement. You’re standing up against people who do not feel the same way as you even if they look the same. So I think the feeling is that these people do hold a lot of strong liberal beliefs, but since it doesn’t come into their life or come into their practice, they don’t have to continue with it until they have to deal, in this case, have to deal with Julian.

VVG: So, Jeff, you open the novel with a quote from the 1857 Oregon Constitution that says, “no free negro . . . shall ever come, trade, reside, or be within this State, or hold any real estate.” So this seems even more extreme than the racial covenants that Whitney has written about in Kansas City, which prevented Black Americans from owning property in certain neighborhoods. So how did Oregon go from that kind of maximalist racism to being a reliably “woke” democratic state, or has it really changed?

JB: I do think it’s changed quite a bit, at least as far as the laws are concerned. I think the last law excluding Blacks from Oregon wasn’t repealed officially until 1926. So it is a recent history. The reason that I have that quote, or that I know it so readily, is because when I was a teacher—I taught language arts and social studies—that’s in our public school curriculum. One of the reasons people try to fight this as a “woke” place, is because they do try to teach kids the history of the place where they’re living. and trying to understand this place.

Transcribed by Otter.ai. Condensed and edited by Hannah Karau. Photograph of Jeff Boyd by Katlin Brown.

Others:

• Ghostbusters (1984) • Go Tell It on the Mountain by James Baldwin • In the Soup: Sean McDonald and Monica West on Publishing During, and After, a Pandemic Fiction/Non/Fiction Season 4, Episode 18 • Revival Season by Monica West • The Fire Next Time by James Baldwin • “On Becoming an American Writer,” by James Alan McPherson from The Washington Post • Fiction/Non/Fiction Season 6 Episode 20: “Remembering an American Writer: Anthony Walton on James Alan McPherson’s Essays and Legacy” • “A Region Not Home: Reflections From Exile,” by James Alan McPherson from Publisher’s Weekly • Ralph Ellison • Association of Writers & Writing Programs (AWP) • Black Lives Matter • The King of Kings County by Whitney Terrell • “In 2021, 10 Hate Groups were Tracked in Oregon,” from the Southern Poverty Law Center • “Why Iowa Has Become Such a Heartbreaker for Democrats,” by Trip Gabriel from the New York Times • Mutual Musicians Foundation • Portlandia (2011-2018) • “The Geometry of Love,” by John Cheever from Journal of Humanistic Mathematics

Fiction Non Fiction

Hosted by Whitney Terrell and V.V. Ganeshananthan, Fiction/Non/Fiction interprets current events through the lens of literature, and features conversations with writers of all stripes, from novelists and poets to journalists and essayists.