Amy Kurzweil on the Open Questions of the Future

In Conversation with Christopher Hermelin on So Many Damn Books

Amy Kurzweil stops into the Damn Library, physically, to talk about the physical object of her new graphic memoir, Artificial: A Love Story, which largely concerns AI. We discuss capturing the details of her screens, the open question of the future, and what we keep from the past to get there. Plus, we delve into the many joys of Jason Lutes’ Berlin, a modern masterpiece, and the underlying prophetic nature of long projects.

Subscribe and download the episode, wherever you get your podcasts!

*

What’d you buy?

Amy: The Hike by Alison Farrell

Christopher: Beautyland by Marie-Helene Bertino // The Invocations by Krystal Sutherland

*

Recommendations:

Amy: This Country by Navied Mahdavian // God, Human, Animal, Machine by Meghan O’Gieblyn

Christopher: Earth Angel by Madeline Cash

*

From the episode:

Christopher: Something that I saw here that I feel like I don’t see in other comics, or other graphic novels, is these screens. Your screens are all over, and you’re actually transcribing emojis from the bank of emojis that they could have chosen. You’re showing the entire array.

Amy: Right. Like when someone’s texting and you see that they chose the crying face and then you see all the other options. I did spend a lot of time drawing screens in the digital world and doing it by hand and doing it over and over again. I didn’t want to copy and paste. I wanted to avoid copying and pasting any images in this book. I mean, there’s some moments where that had to happen, but I really wanted every page that you look at to have every line of ink as its own new line of ink.

Then when I started drawing screens I just realized how much information we are looking at all the time. That was a really interesting revelation in the process of this book. I thought “Oh, I’m just going to draw this website, you know, because I want people to see that I’m logging on to Instagram or whatever.” And the amount of detail in every single slide of Instagram that you’re looking at, the amount of dots and arrows and symbols and pictures and comments and hearts. There’s just so much information that we’re looking at all the time in the digital world. The process of recreating it was like, whoa. The amount of time that it takes you to sit and draw just something as simple as like what you see on your phone.

Christopher: Right.

Amy: That feels like a thesis of the book in a way. That the digital world has an overwhelming amount of information and I’m going to slow down and draw it. What is that going to do for me, and what is it going to do for the reader?

Christopher: Well, it’s also versus this lack of information because the chat bot with your grandfather is incomplete. There’s stuff that you want that isn’t there.

Amy: Mmhmm.

Christopher: Meanwhile, all of this information about you, your life, is fully available. Like you can know the exact moment you were at least sitting down and writing it, you know?

Amy: Yes, definitely. That’s another theme that’s emerging through this project is the idea of using my grandfather’s archives to get to know him. It’s very overwhelming, processing all the information we have saved of him. And yet it’s like probably .00001% of his life. And then, like, when you think about how much information of my life is preserved, it’s still probably like 1%, you know? But it’s enormous. Human life is enormous. Every moment of our experience is just full of information.

And so, the thesis that my father puts forth in the book is information is identity. Possibly one day in the future, we will be able to kind of resurrect identity through preserving and recreating information. When you appreciate how much information there is in a human life, that thesis becomes even more sort of overwhelming. Or even more just mystifying. How could we ever capture that? And yet we capture so much, and we used to capture nothing. So, like, when you think about the future, it really is like an open question whether or not that kind of capture and preservation is possible.

Christopher: One thing that really resonated with me was Fred’s despair. He’s had real trouble with his mental health. But also, I was thinking, too, of the times that I’ve journaled in times of great distress. You’re journaling. You’re already indulging this part of yourself. So you’re like, feeling all of your feelings and sometimes that’s enough to move on. So you get this picture of someone with a dark cloud hanging over their head. But it was only .1%, like you’re saying.

Amy: Right. I mean, a theme that comes up in the book is this question of what do you have preserved? And so then what is remembered of you? And I think especially in the digital world, so much of us have preserved our public self or our professional self. So a theme that comes up with my grandfather is just how much of his archives are this bureaucratic self. Why him as a Holocaust-fleeing Jewish person would be so meticulous about preserving his bureaucratic self?

But then there’s also his professional self, because he was very concerned about getting a job.

So the amount of cover letters in the book, in the archives, there’s just like cover letter, cover letter, cover letter, and they’re all very similar and then there’s all the rejections for the cover letter. It’s like just so much of that. And then there’s this tiny little piece which is his internal life, which are these journals that I find which are very cryptically written and require a lot of interpretation to transcribe. That’s documented in the book.

Christopher: That’s a really beautiful part. When you realize that you can read it, that you can see the letters in his scrawl.

Amy: Right, Right.

Christopher: No one else can.

Amy: Yeah. I mean, there’s what’s typed, there’s what’s handwritten. There’s what I can read that’s handwritten. There’s what I can’t read that’s handwritten. There’s all these levels of what’s interpretable. Then finding that piece of his internal life, which as you noted, is like very dark and full of despair. It’s kind of like the only piece of his internal life that I found. I mean, it was a relief for me to know that he that he had that. But then it’s like, well, how much despair was a part of him? Was it a normal amount? You know, there’s all these questions.

Christopher: But you were writing in his hand, drawing his hand. What was that like?

Amy: That goes back to the element of the book that the process of it was so important to me, especially because it took so long. I was like, I know I’m going to be with this for a long time, you know? So I want the process to be not only have some element of pleasure, but also be meaningful. It was important to me that the book be hand done, and it was important that I, like, spent time with the actual lines of his life.

My process was like, I took all these photos. I mean, there’s also all these levels of digitization and then back to analog and then into digitization again. There’s a lot of movement between those two different modes. I would take photos of his, for example, a letter he wrote, and then it would be in my computer and then I would take my computer to my studio. Because I lived in California and the archives were in Massachusetts. Then I would turn off the lights in my studio, hold up my Arches Hot Press Paper, this thick drawing paper, and trace my computer screen in pencil to get his hand. And then I turn the lights back on, and then I would ink over my own pencil. I did that over and over again for every part of the book that contains some sort of primary document. You trace and then you kind of have to fix the things that you didn’t get right where your hand was quivering. You have to edit a little bit.

But there was this really close looking that happened over and over again with his handwriting and other artifacts from his life. And I just felt like that was a way that I was accessing a certain kind of knowledge that feels important to me. And I guess I would label that kind of knowledge “embodied knowledge.” Like my hand started to learn something about the way that his hand moved.

A big question of the book is like, what is the value out of humans in the future? That’s important to me. I’ve grown up with these ideas that AI is comin’ for us and, you know, there’s a lot of positivity in there that we can talk about, but it’s scary to think about what matters about humanity in a digital, artificially intelligent future. And for me, it was the way that we understand through our bodies. There’s a way in which computers, robots could simulate that kind of knowledge. You know, possibly.

But at least the kinds of machines and algorithms that we’re dealing with now, you know, like large language models and their way of knowing things and understanding things, doesn’t include the mark of the body in the way that the body holds information. It just felt really important to me that it was a part of the process and that that came through to the reader.

*

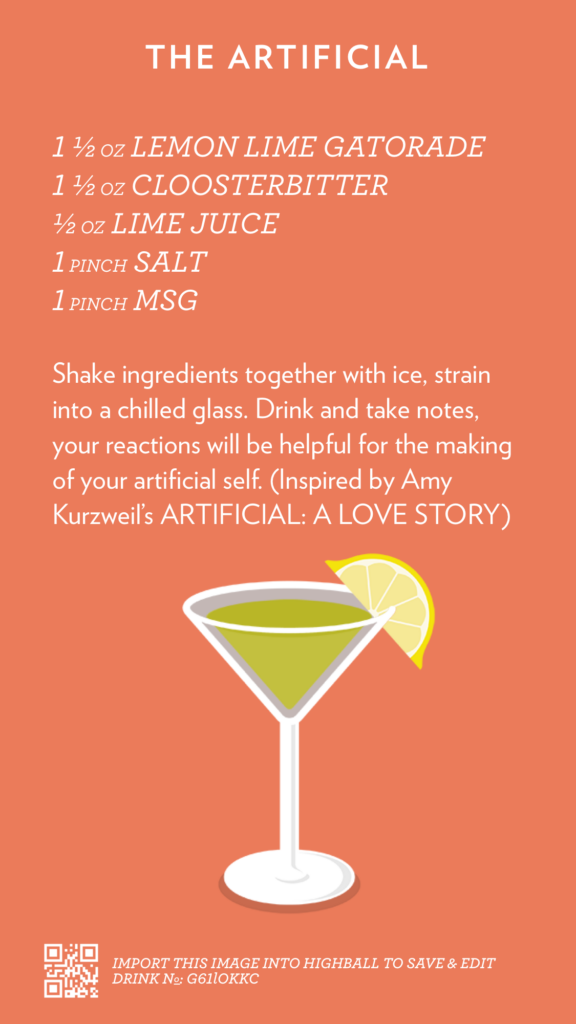

So Many Damn Books

A blessing, a curse, a podcast. est. 2014. Christopher (@cdhermelin) invites folks to the Damn Library to talk about reading, literature, publishing, and trying to make it through their never-dwindling stack of things to read. All with a themed drink in hand. Recorded at the Damn Library in Brooklyn, NY.