American Nightmare: Alice Driver on the Immigrants Who Risked Their Lives at a Meatpacking Plant During Covid

The Author of “Life and Death of the American Worker” in Conversation with Sarah Viren

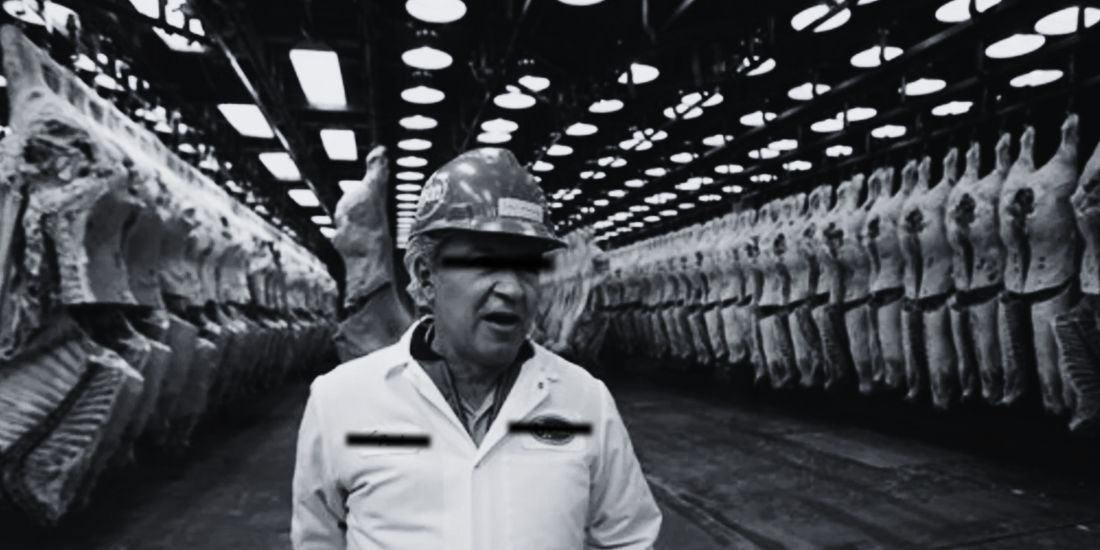

“Nothing is more American than meatpacking,” writes Alice Driver early in her new book Life and Death of the American Worker: The Immigrants Taking on America’s Largest Meatpacking Company. As she then proceeds to show us, little in American life is also more hidden from the general public than meatpacking work.

I can’t remember when I first read Alice Driver, whether it was one of her personal essays in the Oxford American, her investigative work from the border or, more recently, her articles in the The New York Review of Books, including “Their Lives on the Line.” Her book, which draws from those articles, tells the intimate story of a handful of workers from Tyson’s chicken processing plants in rural Arkansas during the Covid pandemic, but woven into that narrative is the much longer tale of the meatpacking industry and the politicians and political landscape that ceded them the power they how wield—to dangerous and at times deadly ends.

Alice and I wrote back and forth via email and Google docs in mid-August, me from my home in Arizona and she from Little Rock, Arkansas.

*

Sarah Viren: Life and Death of the American Worker is a book that you tell us you’ve long wanted to write, possibly since you were a kid growing up alongside meat packing workers in rural Arkansas, but definitely during the last decade of your life as a freelance journalist. You were only able to start work on this book in 2020, though, when you received a grant to interview workers at Tyson’s chicken processing plants.

What changed in the world at large, and possibly also in your personal world, that allowed you to tell this story now?

Alice Driver: In the pandemic, suddenly everyone was reevaluating the meaning of work, of what it means to labor and the conditions of that labor. I had wanted to write about meatpacking workers since 2013 when my mom started volunteering to support a community of several hundred Karen refugees from Myanmar who arrived in Clarksville, Arkansas and worked, largely, at Tyson Foods.

One of my initial ideas was to do a project about the immigrant and refugee workers at Tyson Foods and their gardens. Many immigrant communities grow their own food, which provides a contrast to the work they do in meatpacking, a largely inhumane system for workers and animals, not to mention the environment given the reality of climate change.

I didn’t receive funding to write about meatpacking workers and labor conditions at Tyson Foods, the largest meatpacking company in the U.S. until 2020 when the Economic Hardship Reporting Project and the National Geographic Covid-19 Emergency Fund provided support to work on an article. What started out as one article became four years of my life.

Workers include vulnerable populations such as the undocumented, children, and imprisoned people, and the fear of retaliation by the company has often silenced them.

Meatpacking plants were the second largest sites of Covid infection behind prisons. When workers started dying, their families, many of whom also work at Tyson, became less afraid of retaliation from Tyson because they wanted justice for the dead.

Workers include vulnerable populations such as the undocumented, children, and imprisoned people, and the fear of retaliation by the company has often silenced them. The bravery of the workers who spoke to me cannot be overstated.

SV: Svetlana Alexievich once called her books “novels in voices” and, though there are significant differences in your approach, I thought of that descriptor while reading your book. While you occasionally appear within the narrative as a reporter or observer, you mostly let the people at the center—many of them immigrants from Mexico and Central America who worked at Tyson’s chicken processing plants—tell their own stories in their own words with little interruption or interpretation from you.

Which books were most influential to you when writing and structuring Life and Death of the American Worker?

AD: I studied Spanish at Berea College in rural Kentucky. It was founded in 1855 to educate freed slaves and students with limited economic resources. My experience at Berea College shaped me and my book. The professors and writers I met there have informed my belief in seeking justice and equality through writing.

My Spanish professors, Dr. Margarita Graetzer and Dr. Fred de Rosset, introduced me to the writing of Elena Poniatowska, Rosario Castellanos, Juan Rulfo, and Mario Bellatin. Poniatowska wrote extensively about social movements and social justice in Mexico and her body of work influenced me greatly.

While at Berea, I studied with poet Nikky Finney, spent time with bell hooks, and became friends with classmates C.E. Morgan and Jill Damatac, who write with singular strength and vision. I loved Cristina Rivera Garza’s work since the first moment I read Nadie me verá llorar and Lilliana’s Invincible Summer is a book that lives in me. I completed a Ph.D. in Hispanic Studies with a focus on Latin American literature and then received a postdoctoral fellowship to study at the Universidad Nacional Autónoma in Mexico.

While living in Mexico City, I met Elena Poniatowska in the street and we became friends. I recently interviewed her for the Library of Congress. My literary and poetic universe is informed by a constellation of Latin American writers including Yuri Herrera, Valeria Luiselli, Guadalupe Nettel (who has an incredible short story in which cockroaches are made into ceviche), and Homero Aridjis, who informed the structure of my book.

SV: I was struck, reading, how often language barriers also became safety issues for meat processing workers, like how workers reported that Tyson would ask them to sign release forms and other documents in English, even when the company knows so many of its workers can’t read what they’re signing. As you explain in an author’s note, “language is central to my work, and translation is a literary act.”

Can you talk about the role of translation in this book, both in the reporting and writing process?

AD: I grew up in rural Arkansas, and I didn’t start studying Spanish until I was at Berea College. I have a strong southern accent, and I felt ashamed of that when I spoke Spanish. But I desperately wanted to be fluent. To that end, I completed a masters and Ph.D. in Hispanic Studies at the University of Kentucky. After finishing my program, I moved to Mexico City, where I lived for many years.

I knew that as a journalist and writer, I wanted to work in Spanish. This means that for the past decade, I have been translating my interviews from Spanish into English. Initially I didn’t think of myself as a translator, but it is one of the parts of my process that I love and deeply respect.

If I was not fluent in Spanish, I would not have been able to write this book. Linguistic and cultural fluency is a sign of respect to those I interview, and it was key to building the trust necessary to investigate a global company valued in the billions. I reported most of the book in Spanish and transcribed the interviews.

The hours I spent listening to workers’ voices informed the emotional heart of the book. Translation is about heart, emotion, truth and finding the language that captures the moment—much that goes beyond the technical act of translation.

SV: Another texturing element of this book is the inclusion of photographs of meat packing workers and the landscape of their lives. There is a hint here of James Agee’s Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, although your project foregrounds the writing.

Can you tell me about your decision to work alongside a photographer (or photographers)? What is your hope for how the photographs will be read alongside your writing?

AD: As a journalist, I have long been obsessed with photography—I went through a brief period where I considered going to photography school. But I realized I could center photography in my writing and use my budget, when I was given one, to hire photographers I admired.

When I started working on this project, one of the things that struck me was that in the U.S. we rarely see images of meatpacking workers unless they are produced by the PR departments of meatpacking companies. Liz Sanders is an Arkansas photographer who I’ve known for years, and we drove around the state visiting workers at their homes for four years. In the early pandemic, this work was quite complicated.

Liz moves with a quiet, poetic strength, and her portraits of workers are intimate and show their resilience, commitment, and faith. Many workers didn’t want their faces or identifying details photographed, and Liz created a body of work with the greatest respect for the workers.

While writing articles related to the book, I worked with Mexican photographer Jacky Muniello and National Geographic photographer John Stanmeyer. Jacky is a long-time collaborator of mine, and she navigates complicated projects with ease and humor. I met John working on an article for National Geographic, and his body of work reflects his ability to take a mundane scene and, through pure perseverance, document it in a way that stays with you.

The book and the photos show the workers organizing themselves to demand safe labor conditions. Workers are immigrants, many undocumented; imprisoned people; and children and they are upholding our food system with strength and dignity. We should listen to them and honor their work and lives.

SV: In your “Acknowledgements” section, you talk briefly about how hard it was to write this book, in part the enormity of the project but also because of the emotional toll of witnessing the preventable suffering of so many people. It was, in turn, a devastating book to read.

It should not be cheaper for a company to injure, disable or kill a worker than to provide safe work conditions.

But it was also an empowering one, especially as we learn the stories of workers who risked their lives and livelihood to take part in organized labor movements and an eventual lawsuit against Tyson. I know hope can be a dangerous thing, but what is your hope for how the meat packing industry might change in the next five or ten years, and what would it take to get us to that place?

AD: My hope is that we listen to workers and to the vision they have for the meat packing industry. Organizations founded by workers, like Venceremos in Arkansas and the Coalition for Immokalee Workers in Florida, provide a model for creating change on the state and national level.

In the next five years, I hope the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA), the organization that oversees the meatpacking industry, will be fully funded and staffed. In terms of the fines that OSHA levies against meat packing companies, it should not be cheaper for a company to injure, disable or kill a worker than to provide safe work conditions.

In the next ten, our politicians need to rethink health and safety legislation regarding the meatpacking industry with a focus on creating safe labor conditions and addressing climate change. The first step to getting to that place is for us as a nation to recognize and honor the immigrants who undertake one of the most dangerous jobs in the U.S.

Sarah Viren

Sarah Viren is a contributing writer for the New York Times Magazine and author of the essay collection Mine, which was a finalist for a Lambda Literary Award and longlisted for the PEN/Diamonstein-Spielvogel Award for the Art of the Essay, and the memoir To Name the Bigger Lie, a New York Times Editor’s Choice and named a best book of the year by NPR and LitHub in 2023. A National Endowment for the Arts Fellow and a National Magazine Award finalist, Viren teaches in the creative writing program at Arizona State University.