Feature photo by Rachel Cobb.

The mob of Trump supporters and white nationalists who assaulted the Capitol last week were not the first armed insurrectionists to storm an American seat of government, incited by an authoritarian politician spouting conspiracy theories.

In 1898, heavily armed white supremacists besieged city hall in the port city of Wilmington, NC, overthrowing a multiracial government after shooting dead at least 60 Black men. They were incited by white demagogues determined to eliminate “Negro rule” and “Negro domination” and restore white supremacy.

Both insurrections were fanned by carefully orchestrated campaigns of lies and disinformation—what President-elect Joe Biden has called “the big lie” perpetrated by President Trump and his enablers in Congress and right-wing media. For weeks, the Capitol rioters were fed false claims that the 2020 election had been stolen, ultimately igniting a siege of the Capitol to “stop the steal” of the electoral college vote certifying Biden’s victory.

Biden has called the mob “a bunch of thugs, insurrectionists, white supremacists, anti-Semites” who enjoyed “the active encouragement of a sitting president of the United States.” Part of that description could also apply to the 1898 insurrectionists in Wilmington, where white demagogues incited them to violence against Black men and their white allies.

Trump supporters breached police barricades and stormed the US Capitol last Wednesday. Photo by Rachel Cobb.

Trump supporters breached police barricades and stormed the US Capitol last Wednesday. Photo by Rachel Cobb.

Both uprisings erupted after a bitterly contested election. Both descended into violence after impassioned speeches demanding vengeance and retribution. And both were spurred by deep-seated fears and grievances among white men convinced that their very country had been stolen from them.

The rioters at the Capitol chanted “USA!” and “Take back our country!” The white supremacists of 1898 mounted a call and response as they coursed through the streets searching for Black men to kill: shouts of “White men!” followed by cries of “Victory!”

Last week, the mob that invaded the Capitol included white supremacists stoked in part by Trump’s depiction of majority Black districts of Atlanta, Philadelphia and Detroit as cesspools of voter fraud and ballot-stuffing.The sight of Confederate flags unfurled inside the Capitol 156 years after the Union survived the Civil War appalled many Americans last week. But the Confederate flags carried by white supremacists in 1898 were cheered by a white populace incited to destroy a rare post-Reconstruction model of multiracial cooperation.

Wilmington was an existential threat to white supremacy. It was perhaps the most racially inclusive city in the South. A coalition of Black voters and white Republicans—the progressive party of Lincoln at the time—elected a ten-man city council that included three Black men. Ten of the city’s 26 police officers were Black.

Black men served as justices of the peace, superintendent of streets, county jailer and county treasurer. The federal collector of customs at the bustling Wilmington port was a Black man who earned $4,000 a year—or $1,000 more than the white governor. A defiant Black man edited a Black daily newspaper that was burned to the ground the day of the coup.

White supremacist newspapers and politicians launched a sophisticated White Supremacy Campaign designed to prevent Black men from voting or holding public office. White men were told that Black voters and Black public officials had stolen their birthright—the unassailable right to rule over subservient Blacks. White men were further inflamed by false claims, spread by white supremacist newspapers, that Black men were stalking and raping white women.

Leading the propaganda campaign against “Negro rule” was a race-baiting executive of the state Democratic Party, Josephus Daniels, who also happened to publish the most powerful newspaper in the state, the News and Observer in Raleigh. The day was coming, Daniels reported, when white men “will take the law in their own hands and by organized force make the negroes behave themselves.”

Daniels’s co-conspirator, Democratic state party chairman Furnifold Simmons, assured white voters, “The Negro shall know his place.”

The n-word appeared regularly in print and was wielded as a weapon by white supremacist politicians in stump speeches. For the 25 percent of white voters who were illiterate, Daniels published cartoons depicting Black men as vampires, thugs and rapists.

Daniels knew how to stoke the insecurities of fellow southern white men, emasculated by Union troops who once occupied Wilmington and threatened by Black men elevated to positions of public authority.

Between Election Day and the Capitol riot, Trump’s family and acolytes sent out more than 200 aggrieved Twitter posts falsely alleging widespread election fraud.Daniels’s News and Observer also launched a fake news campaign against the “Black beast rapist,” falsely reporting that “the prevalence of rape by brutal negroes upon helpless white women has brought about a reign of terror.”

Last week, the mob that invaded the Capitol included white supremacists stoked in part by Trump’s depiction of majority Black districts of Atlanta, Philadelphia and Detroit as cesspools of voter fraud and ballot-stuffing. It was a coda to Trump’s four years of dog whistles to white nationalists that the very face of “their” America was becoming Black, brown and immigrant—the very outsiders who had now helped steal an election.

Photo by Rachel Cobb.

Photo by Rachel Cobb.

As the historian Timothy Snyder has written of Trump, “His use of the phrase ‘fake news’ echoed the Nazi smear Lugenpresse (‘lying press’); like the Nazis, he referred to reporters as ‘enemies of the people.’”

Trump’s inflammatory rhetoric reached a tipping point after Election Day. He amplified the stolen election lie, providing no evidence of fraud even as election results were scrutinized and confirmed by Republican state officials and validated nearly 60 times by state and federal judges, many appointed by Trump.

Between Election Day and the Capitol riot, Trump’s family and acolytes sent out more than 200 aggrieved Twitter posts falsely alleging widespread election fraud. To promote the Jan. 6 rally that later incited his followers to ransack the Capitol, Trump tweeted Dec. 19, “Be there, will be wild.”

At the rally, Trump told a frenzied crowd, “We’re going walk down to the Capitol . . . We gotta get rid of the weak Congress people.”

Donald Trump Jr., also speaking at the rally, warned members of Congress who refused to amplify his father’s cries of election fraud, “We’re coming for you!” And Donald Trump’s lawyer, the feral Rudy Giuliani, implored the crowd to settle the election dispute via “trial by combat.”

The Capitol insurrectionists failed to overturn the 2020 election. But the 1898 mob mounted America’s only lasting, violent overthrow of an elected government. After removing the mayor, city council and police chief at gunpoint, the rioters appointed mob leaders in their place.

Journalists from the New York Times and the Washington Post, among others, amplified for northern readers disinformation that Wilmington’s Black men were plotting to riot, murder white men and rape white women.The coup re-established white supremacy as official city and state policy until the 1960s and ushered in Jim Crow laws that prevented North Carolina’s Black citizens from holding public office or voting in significant numbers for the next 60 years.

Two years before the coup, 126,000 Black men registered to vote in North Carolina. By 1902, the coup had whittled the number down to just 6,100.

In the 21st century, Black citizens have complained of voter suppression tactics by conservative white politicians determined to dilute Black voting power through voter ID laws, voter roll purges and gerrymandering schemes. Those strategies were perfected by the white supremacist leaders who organized and carried out the 1898 coup.

Promises of a violent white insurrection in 1898 prompted the nation’s biggest newspapers to send reporters—all white, of course—to Wilmington to cover the “race war.” Journalists from the New York Times, Washington Post and Philadelphia Inquirer, among others, amplified for northern readers disinformation that Wilmington’s Black men were plotting to riot, murder white men and rape white women.

The city’s white mob was led by a truly Trumpian figure—Col. Alfred Moore Waddell, a grandiloquent former Confederate officer. Waddell was a dynamic, often mesmerizing speaker who excelled at stoking white rage and grievances. He and other white supremacists falsely claimed that Wilmington’s multiracial government had stolen the election that put it in office.

The night before the Nov. 8 midterm election, Waddell delivered an incendiary speech to hundreds of agitated white men brandishing Winchester rifles.

“You are armed and prepared and you will do your duty,” Waddell told them. “Go to the polls tomorrow and if you find the negro out voting, tell him to leave the polls. And if he refuses, kill him! Shoot him down in his tracks!”

In a speech two weeks earlier, Waddell told white gunmen to “choke the Cape Fear River with carcasses” of Black men.

White vigilantes known as Red Shirts—the Proud Boys of the day—spent much of 1898 breaking into Black homes at night. They whipped Black men and warned they would be killed if they dared register to vote. Wilmington’s white merchants fired dozens of Black employees for registering.

On election day, Red Shirts intimidated and beat Black men, preventing many from voting. They stormed voting precincts, destroying Republican ballots and replaced them with Democratic votes, stealing the election for white supremacist Democrats.

White vigilantes known as Red Shirts—the Proud Boys of the day—spent much of 1898 breaking into Black homes at night.Two days later, on Nov. 10, a mob of nearly 2,000 armed white men burned the Black newspaper offices and hunted down and shot Black men in the streets. The killing spree sent hundreds of terrified Black families into the woods and swamps for two frigid nights. More than 2,100 Blacks soon fled the city forever.

Wilmington was 56 percent Black in 1898. Today, it is 18 percent Black.

The coup inspired white supremacists across the South. As whites in Georgia plotted to steal an election in 1906, they consulted the Wilmington coup leaders for advice. M. Hoke Smith, elected governor of Georgia after a race-baiting campaign, said of Georgia’s Blacks, “we can handle them as they did in Wilmington,” where he said the woods were “Black with their hanging carcasses.”

No one was ever held accountable for the Wilmington murders and coup. The federal government refused to intervene, and North Carolina’s state government was taken over by white supremacists who ruled for six decades.

Daniels went on to serve as Secretary of the Navy and ambassador to Mexico. Simmons served three decades as a US Senator. At least three stump speakers from the White Supremacy Campaign were later elected governors of North Carolina.

Some rioters from last week’s insurrection have been arrested, and law enforcement authorities have vowed to punish others. But President Trump has not been held accountable for inciting the riot, other than being stripped of his Twitter and Facebook megaphones and threatened with impeachment. Nor have his allies in Congress or the media.

But even as more arrests are made, the big lie about a stolen election continues to metastasize on right-wing and white nationalist social media sites, promising yet another violent American reckoning.

__________________________________

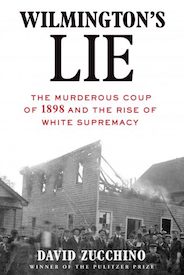

Wilmington’s Lie by David Zucchino, is available from Grove Atlantic.