America in Mosul: An Account of the Occupation

of an Iraqi City

James Verini on the Shifting Relationships Between Moswalis,

Daesh, and the Troops

During the battles for Ramadi and Fallujah, those cities emptied out, their residents leaving for camps or fleeing to safety in other parts of the country or world. The Mosul operation was vastly more complicated because so many Moslawis didn’t leave, at least not immediately. Some stayed because the Caliphate was executing people who tried to escape the city, some because they refused to abandon infirm family members or leave their houses to be looted, some because they’d worked with the Caliphate in some capacity—many, many more Moslawis had done this than will ever admit to it—and worried they’d be killed or imprisoned.

But most stayed because they were asked to. In the days before the Mosul operation commenced, the military dropped leaflets from helicopters onto the streets, requesting residents not flee. They would be protected, residents were assured. The Iraqi security forces had changed. They were no longer in the business of abusing their fellow citizens. Moslawis would be safe.

The generals decided on this tack in part because three million Iraqis had already been displaced by the war against the Islamic State by the time it reached Mosul, and the country could not absorb another mass exodus. But the generals were also placing a wager: that they could use the civilian population to their advantage. Their intelligence suggested that, after two and a half years of deprivations and depravations, Moslawis’ anger at the Islamic State was as hot as it had been at the government before the city’s fall. If the security forces behaved, Moslawis could be a source of assistance, intelligence, good publicity.

And at first the wager paid out. The troops saw protecting Moslawis as no less important than killing jihadis. They treated civilian wounds, helped them salvage their homes, bury their dead, gave them food and cigarettes, played with their kids. The Moslawis in turn opened their homes to the soldiers, cooked for them, warned them of booby traps and weapons caches, helped them identify collaborators.

In the battle’s first months, the soldiers were greeted as saviors, with tears and kisses, hugs and hosannas. The jihadis had been greeted by many Moslawis as saviors, too, it is true, and a lot of the people now kissing and helping the soldiers would, three years earlier, have run them out of town, but the effusion was no less sincere for that, I am convinced. There was a real mutual understanding, Moslawis having lived under the Caliphate for so long, the troops having fought it for almost as long.

Some soldiers were frustrated with the slow pace of the siege and blamed the bothersome residents, or saw all Moslawis as insurgents—but most soldiers I got to know, like Karim and Ali and Rasul, genuinely felt for Moslawis, admired their resilience and stoicism. This though most of the soldiers were Shia, from Baghdad and points south, while most Moslawis were northern Sunni Arabs. You could call it a suspension of disbelief. The deeper function, I sensed, was a certain native preference for forgiveness.

The interactions between the civilians and troops could be heartening, or disturbing, or funny, or heartbreaking, sometimes all of those things. They were always interesting.

In the battle’s first months, the soldiers were greeted as saviors, with tears and kisses, hugs and hosannas. The jihadis had been greeted by many Moslawis as saviors, too, it is true.

One day, I witnessed this scene:

By December, the troops had fought their way to a neighborhood called Adan, about halfway between Zahra and the Tigris. CTS troops were conducting a food distribution at an intersection, where hundreds of Moslawis had gathered. As usual, there were not enough ration boxes, and the crowd shouted and raced among the trucks, vying for what was left. Soldiers fired into the air to try to keep order.

At the command post, in a commandeered house, they bundled into the courtyard a middle-aged man in a greasy blazer, tracksuit pants, and sandals. He had been caught driving a car. In the military-controlled sectors, Moslawis were not allowed to drive vehicles other than donkey carts. The man was softly protesting his innocence to a lieutenant.

“I wasn’t—”

“Don’t raise your voice with me!” the lieutenant barked. “What are you doing? You’re saying you weren’t helping Daesh?”

“No, I wasn’t helping them. I was only using the car.”

“You were using the car to help them.”

“I, well, that is—”

“So what, you were just playing with the car?”

“I swear to God—”

“Leave God out of it. If God had any luck, he wouldn’t have given you your brain. Who do you think you’re fooling? What were you doing with the car?”

“I helped a family.”

The lieutenant snorted contemptuously. The man improved his posture and, clearing his throat, attempted to change his tone to one of solemn formality.

“My dear sir,” he commenced, “please allow me to—”

But the lieutenant was now on his phone. The man looked to one of the soldiers and said, “You see, it was only me and my brother. . .” as he was led inside.

A woman entered the courtyard with her teenage son and young daughter. The lieutenant greeted her warmly and familiarly as she confidently pulled off her chador. The lieutenant led her and her children through the house into a back room. He pulled back a heavy curtain to reveal floor-to-ceiling windows and a glass door leading onto a narrow deck and a high dividing wall. This family lived in the house on the wall’s other side. They had left when the fighting in Adan had begun, a few days earlier, and now they couldn’t return to their house because the street on which it sat was the front line. But they could get to it through the command post. Each day, the lieutenant helped them check on their home.

Her son, who appeared to be about thirteen, bounded up onto the wall and from there leapt onto a metal awning on the second floor of their house. The daughter, perhaps seven, held her mother’s hand and they both followed the boy with their eyes.

“Go in through the window,” his mother called.

“I know, Mom,” he called back.

“They broke it anyway,” she added to the lieutenant.

“It’s okay, just check,” he said, “see what’s there.”

“Our neighbor’s place was hit by a mortar,” she said.

Her son yelled something.

“Open the door to the kitchen!’ she yelled back, and, to the lieutenant, ‘You think I’m scared, but I’m only afraid of God.”

He smiled.

The son emerged, threw a scarf to his mother, and leapt down.

“God bless your family,” the lieutenant said as he led them back out.

While most soldiers I knew did go to great lengths to protect civilians, the favor was not extended to suspected jihadis. If you spent time in Mosul, you eventually saw prisoners beaten, tortured, and, with enough time, murdered.

A journalist friend was with a band of federal police. He awoke in the middle of the night to gargled screams. He sat up to see a prisoner with wires attached to his appendages. The police were sending electricity into the man. A group of soldiers I spent a night with showed my colleague a video of them decapitating a prisoner with a small, blunt knife. A major I met had trained as an attorney. When the war was over he wanted to practice human rights law. He had a policy of summarily executing captives he believed to be jihadis.

While most soldiers did go to great lengths to protect civilians, the favor was not extended to suspected jihadis. If you spent time in Mosul, you eventually saw prisoners beaten, tortured, and, with enough time, murdered.

When I asked how he squared this with his professional aims, he explained the Islamic State had forfeited its human rights. “It’s true we have human rights here and that sometimes terrorists get trials, but Daesh doesn’t deserve anything like that. They kill innocents at every opportunity.” I offered no rejoinder to the major. He was killed by an IED not long after.

Most of the interactions I saw between soldiers and suspected jihadis were more ambiguous. One day I watched this:

I was sharing a hookah with a sergeant when a middle-aged man approached. His teenage son dragged his feet alongside him. The man wanted to turn over his son, he explained to the sergeant, because he had taken a job as a street cleaner with the Islamic State. The job had lasted ten days, a year earlier. The sergeant, whose name was Salam, wasn’t overly interested. Nor was the son, Idris, whose expression suggested this was only the latest in a years-long litany of paternal complaint. Salam, the left side of whose head was mottled by a burn scar, asked the father why he was only turning in Idris now.

“Because yesterday the minister announced that those who worked for Daesh but did not bloody their hands will be forgiven,” the father said. “I swear, he has not done anything bad. If he had, I wouldn’t have turned him in. I would have helped him escape.”

Salam asked Idris if what his father said was true. Idris said it was. He’d been a student but dropped out when the Islamic State took over his school, he explained, and went to work at his uncle’s tea shop. The religious police shut it down because of the hookahs, he added, looking at Salam’s hookah.

“Did you take the job because you needed the money?” Salam asked.

“Yes,” Idris said. “I needed money to buy a motorcycle.”

I laughed, then stopped laughing when I saw no one else was laughing. I was the only one among us who found this funny, apparently.

“He’s a young man,” the father said. Salam nodded. A young man, a motorcycle—fair enough. But, his father went on, he didn’t want Idris riding a motorcycle, and while he liked that his son was motivated to get a job, he didn’t want him working for the Caliphate. Salam nodded. On top of everything else, the father continued, Idris had informed his boss in the Islamic State of his father’s contempt for the group.

“He told them I didn’t like them,” the father said. “That’s why they jailed me and beat me.”

A small audience of locals and soldiers had gathered by this point, each newcomer being filled in on the family drama, and they murmured disapprovingly when they heard this. However, when Idris and his father agreed that, whatever else their faults, the Islamic State had taken sanitation very seriously, the audience murmured in agreement.

“Don’t lie to me,” Salam said to Idris. “Did you join Daesh because you fought with your father?”

Idris shrugged.

“Yeah.”

“This is what happened in Mosul—every kid who fought with his dad joined Daesh,” Salam said. ‘Well, if he didn’t do anything bad, he can just go.”

When Idris and his father agreed that, whatever else their faults, the Islamic State had taken sanitation very seriously, the audience murmured in agreement.

Another soldier intervened. He was short and athletically built, with a necklace and teeth that competed for space in his mouth. He had the air of one those lesser players on the high school football team who makes up for his lack of field time with arbitrarily cruel tackles of his teammates during practice.

“So you were only a garbage man?” he said to Idris. “You could have at least been a fighter.”

He stepped behind Idris and belligerently caressed his neck with one hand. With the other he dangled over Idris’s shoulder an adjustable wrench. It was too small to be overtly menacing, but he turned it in his palm and retracted and clamped the jaw in such a way to suggest it held torturous possibilities Idris could only imagine. The boy’s eyes went wide.

“Ibrahim, have you become an investigator?” Salam said.

“How do we know if his file is clean?” Ibrahim said. “What if later we find there’s more to it?”

“If we take in everyone who’s worked with Daesh at some point,” Salam said, ‘we’ll have to take in all Mosul.”

Idris’s father, by now clearly regretting his decision to turn Idris over, repeated that he was certain his son had done nothing wrong. But it was too late. Idris was brought into a requisitioned house and patted down. In a back bedroom, his ankles and wrists were tied with cloth and he was pressed onto the floor. Ibrahim came in and sat on the bed across from him.

“Look at you. Just look at you. You were even working with them. We’ll just wait for the intelligence officer and then we’ll see.”

The intelligence officer arrived with Idris’s father in tow.

“So you’re saying your son hasn’t done anything and that you’re turning him in just for being a garbage man? This makes no sense,” the officer said. And to Idris: “Let me give you some advice. Just be honest with us. Tell us everything. If you don’t tell us the whole story now, and we find other sources who tell us more, you know what will happen? You’ll just be killed and tossed in the street with the rest of Daesh.”

Over the course of the afternoon, locals filed in to have a look at the captive. Idris looked up at them blankly, they down at him unimpressed. Ibrahim and a younger, gentler soldier walked in and out of the bedroom, addressing Idris with threats and placations. They appeared to want to enact a good-cop, bad-cop routine, a vaudevillian one. The gentle soldier brought Idris a foam container of rice and tomato sauce, and untied his wrists. Idris said he wasn’t hungry.

“Animal!” Ibrahim yelled at him. “If he tells you eat, you eat! Drink, you drink! If one of us tells you that you have to throw yourself into a fire, you’ll do it.”

“Listen, we’re not telling you to throw yourself in a fire,” the gentle soldier said. “We’re just telling you to eat.”

“This animal here, we tell him to eat, and he won’t. Son of a donkey! Animal! Son of a sheep!”

Another soldier came in and said to Idris, “Imagine if you get married one day and have kids, and your son goes and does something like you’ve done. How would you feel?”

Idris ate. After lunch, Ibrahim took a nap on the bed across from him as Idris looked on. When he awoke, Idris said he wanted to pray.

“Of course, now you want to pray! If I were you, and had decided to join Daesh, I would have at least worked in a supermarket, something that would have fed me. Not a garbage man. They’re garbage, and you were their garbage man. Garbage and garbage! How did you come up with that? What’s the matter, your head isn’t clear? Let me clear it for you.”

Ibrahim slapped Idris.

“Is it clear now?”

“I swear I’ve done nothing,” Idris whimpered.

“Don’t worry,” the gentle soldier said. “It will be all right.”

Every CTS position I saw in Mosul was as insecure as the one in Zahra. No checkpoints, no regular sentries, sometimes not even a perimeter. Locals wandered in and out. The soldiers were usually obliging.

Every CTS position I saw in Mosul was as insecure as the one in Zahra. No checkpoints, no regular sentries, sometimes not even a perimeter. Locals wandered in and out. The soldiers were usually obliging. Near the triage station in Gogjali, on a slope overlooking east Mosul, was a nascent neighborhood, a scattering of freestanding structures, half- finished homes, cinderblock foundations. Some were inhabited by their owners or refugees, others abandoned. One of the latter, a modest one-story house that once aspired to two stories, had held enemy fighters or served as a stopping place for them as they tried to escape the city. On the cement floor of the small courtyard was a discarded Rhodesian ammunition chest rig and by that, in a sink, a pile of hair of what had once been a beard. Occasionally you came upon just such perfect tableaux.

CTS had moved in. To my untrained eye, this at first appeared to be just another command post in a requisitioned home like the one in Zahra. Someone better versed than myself in the instruments of high- tech warfare would have understood the significance of the large aerials on the roof and on the APC idling in front. What I noticed was that, on the ground floor, the soldiers who sat on the overstuffed wall-to-wall sofa set smoking and drinking tea and studying their phones, as they would have done in any command post, were also shooting covetous glances at the stairwell, on which they were not permitted. It wasn’t until I ascended the stairs that I saw why this was: on what would have been the second level, and was now instead a kind of terrace, was the coalition’s forward air command. From here the air war on Mosul was being directed. It was a sparse and alarmingly vulnerable affair.

__________________________________

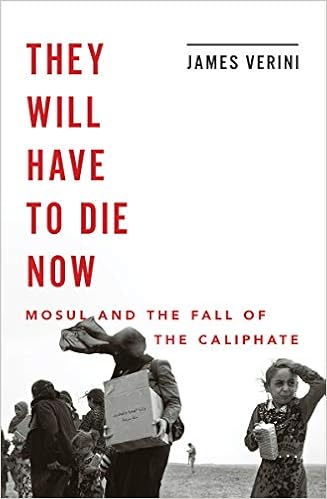

Excerpted from They Will Have to Die Now by James Verini. Copyright © James Verini 2019. Reprinted with permission from Norton.

James Verini

James Verini is a Contributing Writer at the New York Times Magazine and National Geographic. He has also written for The New Yorker, The Atavist, and other publications, and has won a National Magazine Award and a George Polk Award.