Amanda Churchill on Embracing Her Japanese Heritage Through Food

“I wondered why it was Japanese food that I couldn’t get out of my mind.”

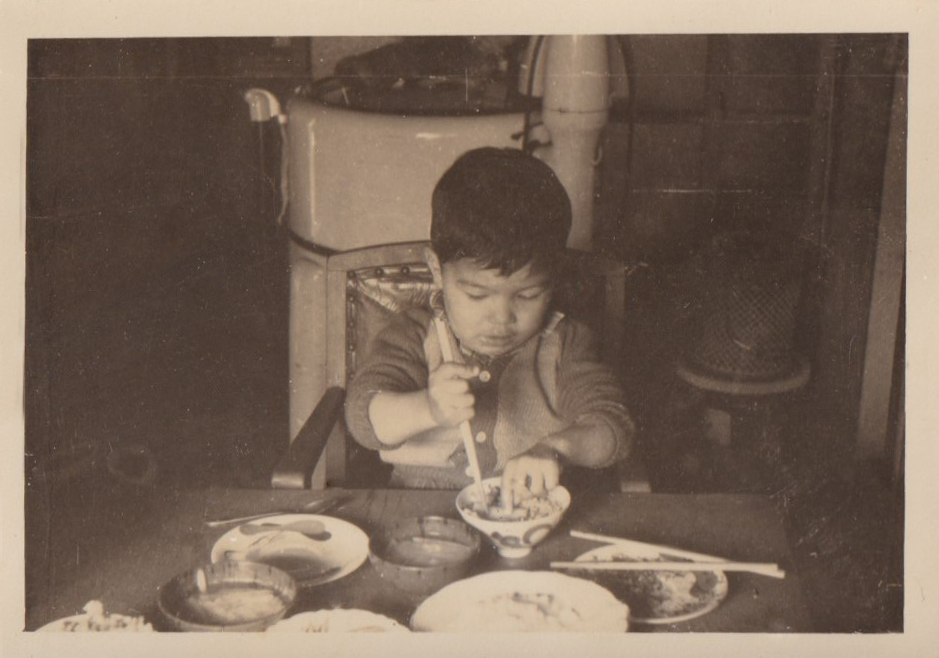

All photos courtesy of the author.

As a little girl, I was a huge disappointment to my Japanese grandmother when it came to food. She loved me, that was clear, and she liked my nose, once tracing the bump on the bridge and nodding with encouragement, was a fan of my excellent grades and thought my sketching skills were promising. But, when it came to meals, she would sigh and inevitably—I’m embarrassed by this now—pull out a can of Spaghetti-Os with Meatballs. She knew it was my favorite.

“Mahndeeee, this not good for you,” she once said as opening the can and wincing at the sight and smell. That afternoon I had already turned up my nose at her leftovers, something I called “rice with stuff.” The stuff: pickled ginger, daikon, bright yellow egg, dried seaweed, tender tofu. My cousins ate it, she told me, your cousins love it. It is Japanese kid food. It’s what you eat, and she said the next part very slowly, if you’re Japanese.

Her words made my ears burn. I looked down at the Spaghetti-Os, but I had no appetite.

It wasn’t until late high school that I learned to love her food. I ate the chirashizushi (“rice with stuff,” or, actual translation of scattered sushi) and the rolls with their bright pickled vegetables in the center, held tight in green-black nori. I’d watch my grandmother squat near a round Coleman camping grill, her own version of a hibachi, and carefully turn the yakitori, batting off help from my father and aunts.

If we were nearby and lucky, she’d take her chopsticks and tear a piece off a skewer and put it, lava hot, on our tongues. Gyoza, miso soup, always. Pickled cucumber salad sliced so thin you could see through them. But my favorite was my grandmother’s inari, deep fried and sweetened tofu pockets stuffed with rice and topped with furikake. I called them “little brown bags,” my cousins called them “honey pockets.”

And there were the foods that only my grandmother, father and aunts ate: niboshi, crisp-dried anchovy; natto, sticky fermented soy beans; katsuobushi, dried, soaked and then fermented bonito flakes. Even the most adventurous of Kyosaki-Gann grandkids shrank back when offered one of these Japanese favorites.

But the ingredients for these foods, all of them, were hard-won, which made my earlier distaste for them even more heartbreaking. When my grandmother arrived in rural north Texas in the late 1950s, there were obviously no Asian groceries nearby. My aunt June, nearly eight years old and only accustomed to Japanese food, refused to eat American style dishes when the family arrived and my grandmother quickly became worried about her weight dropping, her health.

So, she went forth adapting her menu. Spaghetti noodles instead of ramen, powdered ginger instead of fresh, long-grain rice instead of short-grain Japanese. She could easily find everything to make okonomiyaki, Japanese green onion pancakes, so these became a staple and something my father and aunts recall fondly.

But to taste home again, the family depended on what shelf-stable items my great uncles could afford to send, if at all. When rice crackers arrived from home, they disappeared within hours, split among the family like jewels. My father recalls getting a package of nukadoko and skipping through the house—finally his mother could make his favorite pickles. The fermented rice bran was essential in getting the right texture and flavor. Cans of soy sauce would occasionally be sent and rationed, watered down to last longer.

I was in my first trimester with my first child when the cravings for Japanese food hit. Not food from a sushi restaurant, not a bento box from a place in the mall, the food I ate with my family.

We were in Nice, France, though, and my husband and I traipsed all over for some semblance of Japanese food, only to settle with microwave white rice and packets of soy sauce from a small Chinese food stand. I thought we would fare better in Paris, our next stop on the trip, so I held out hope.

I felt a fizz of happiness inside me. She was calling me Japanese. Something lifted and something fell into place.

Again, we walked all over looking for just the right flavors. We did find sushi. I skipped the fish, but what I wanted, more than anything, was the inari. I could taste it—the sweet and savory flavor of the fried wrapper, the bumpy, slightly spongy texture, the vinegar bite, the pop of salt from the seaweed and roasted sesame seeds stuck to the rice. One night we took alleys and backways, trying to reach a restaurant my husband had found online and used Google to translate.

A Japanese restaurant opened in 1958, an elderly Japanese woman as owner, homecooking. It was the 2nd arrondissement. We located it on a map and began our hike, only to find it closed because of a plumbing leak. I sat on the low step outside. I actually wept.

Tucked into bed that night, I wondered why it was Japanese food that I couldn’t get out of my mind. I fell asleep dreaming of rice.

While researching my first novel, inspired by the life of my grandmother, I found story after story of how impossible it was to locate rice in Japan not only during the war, but also during the following American occupation.

My grandmother had told me one snippet of a memory from that time but encountering the scope of my own ignorance in those pages of history was staggering. She had explained to me that the only way she could provide food for her parents and siblings was to visit the black markets, using American goods bought at the P/X and trading them for bags of rice that she would then ship, using a friend back home, to the village where her family still lived. This family, however, did not fully approve of her marriage to an American soldier, much less the baby that was on the way. Yet still, she tried to honor her family, even through dishonorable means.

In my research I eventually came across information about the black market I felt certain my grandmother visited, an open-air exchange near the Uneo station. Looking at photos, somehow taken from above, thousands are gathered near tables in the shadows of buildings. I think of my grandmother, braving this crowd. And how similar it was to her early years in Texas where she braved a different kind of crowd at the local grocery store. A family hungry for sustenance, a woman desperate to provide it.

When I finally returned home from that trip abroad, I visited my grandmother’s house where she was still living with the help of daily caregivers and she was even thinner than when I’d left. She had survived stomach cancer and a total gastrectomy in the years before and had been advised by her doctors to eat small meals many times a day in order to maintain her nutrition, and to cut out smoking. She had, as was her way, refused to do both, instead eating as she always had and lighting up just as often.

But no matter what she ate or how, her body, without a stomach, could not break down enough of the nutrients. Many elderly do not live long following a gastrectomy and because of this, it is rarely recommended. By then she was her fifth year without a stomach and she would last another five years, three times the median number of years that most her age survive.

We sat at the kitchen table, the same one that now was far more scratched than when I was a child, a few cigarette burns from forgotten smokes on the edges. We opened a fresh bag of rice crackers, then another. I told her about the weird food cravings in France and she nodded, taking in my story. She didn’t laugh, like I thought she would, but was instead thoughtful.

“You know, Mandy, Japanese women always crave rice when pregnant. This not so weird. And when you have a baby girl inside, you want sweet things.”

I felt a fizz of happiness inside me. She was calling me Japanese. Something lifted and something fell into place. I didn’t dare remind her of the Spaghetti-Os and of what she said to me so long ago. And she had predicted correctly. I would soon find out that, indeed, I was pregnant with a daughter.

We stayed that way for a while, pushing the crackers back and forth between us, our hands sometimes in the bag at the same time, reaching for the best ones.

__________________________________

The Turtle House by Amanda Churchill is available from Harper, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.

Amanda Churchill

Amanda Churchill is a writer living in Texas. Her work has been featured in Hobart Pulp, Witness, River Styx, and other outlets. She was a Writer’s League of Texas 2021 Fellow and holds a Master of Arts in Creative Writing from the University of North Texas. The Turtle House is her first novel.