Alli Warren Translates Five Books into Poems

From W. E. B. DuBois to Bernadette Mayer

I am a writer because I am a reader. I read in order to secure a foothold in the world. Reading brings me out of myself, and I’m trying to remind myself of this during the quarantine. One thing I know how to do is hunker down with books. I find comfort in books that remind me the world is not constrained by the limits of my tiny consciousness, by the here and now. I mostly read books that remind me that this hellfire world has a history, a context, that it didn’t emerge out of thin air and that it doesn’t have to be this bad, it doesn’t have to feel this way. These books place me in a context of solidarity with others, an ecology in which I feel less alone.

I am with those no longer living, with those currently living who I don’t (yet?) know, with those yet to be born who will come into the world we make for them. I read to educate myself and to broaden my perspective and to learn how to think and fight and to remind myself that human history is a blip. Books aren’t the only source of this insight, of course—staring up at the sky, talking with friends and lovers, listening to birds yakking, all means to this end. Reading is a way of looking in in order to look back out with altered vision.

So, during the spectacle of this US election season, while a pandemic unfolds in us, around us and among us, hoarding and hunkering, I return to some books that have helped ground me and given me this long-seeing perspective, and from their words I made some poems. These are not my words, they are the words of their authors—I just translated them into poems, so that we can sing them and remember (poetry is a technology of memory), building up community memory, humming these fight songs.

*

Peter Linebaugh and Marcus Redicker, The Many-Headed Hydra

The emphasis in modern labor history

on the white, male, skilled, waged, nationalist,

propertied artisan/citizen or industrial worker

has hidden the history of the Atlantic proletariat

of the seventeenth, eighteenth, and early nineteenth centuries.

That proletariat was not a monster

it was not a unified cultural class

and it was not a race.

This class was anonymous, nameless…

It was landless, expropriated.

It lost the integument of the commons

to cover and protect its needs.

It was poor, lacking property, money

or material riches of any kind.

It was often unwaged

It was often hungry

It was mobile, transatlantic

It powered industries of worldwide transportation.

It left the land

migrating from country to town

from region to region

across the oceans

and from one island to another.

It was terrorized

subject to coercion.

Its hide was calloused

by indentured labor

galley slavery

plantation slavery

convict transportation

the workhouse

the house of correction.

Its origins were often traumatic:

enclosure, capture, and imprisonment

left lasting marks.

It was female and male of all ages.

It included everyone

from youth to old folks

from ship’s boys to old salts

from apprentices to savvy old masters

from young prostitutes to old ‘‘witches.’’

It was multitudinous, numerous, and growing.

Whether in a square, at a market

on a common

in a regiment

or on a man-of-war

with banners flying and drums beating

its gatherings were wondrous to contemporaries.

It was numbered, weighed, and measured.

Unknown as individuals or by name

it was objectified and counted

for purposes of taxation, production, and reproduction.

It was cooperative and laboring.

It moved burdens, shifted earth,

and transformed the landscape.

It was motley, both dressed in rags

and multiethnic in appearance.

It included clowns, or cloons.

It was without genealogical unity.

It was vulgar.

It spoke its own speech

with a distinctive pronunciation, lexicon,

and grammar made up of slang,

cant, jargon, and pidgin—

talk from work, the street,

the prison, the gang, and the dock.

It was planetary

in its origins, its motions, and its consciousness.

Finally, the proletariat was self-active, creative;

it was—and is—alive;

it is onamove.

*

Silvia Federici, Caliban and the Witch

If we consider the historical context

in which the witch-hunt occurred

the gender and class relations of the accused

and the effects of the persecution

then we must conclude that witch-hunting in Europe

was an attack on women’s resistance

to the spread of capitalism relations

and to the power women had gained

by virtue of their sexuality

their control over reproductions

and their ability to heal.

The battle against magic

has always accompanied the development of capitalism

magic is premised on the belief that the world is animated

unpredictable and that there is a force in all things

The capitalist organization of work must refuse

the unpredictability implicit in the practice of magic

Just as the enclosures expropriated the peasantry

from the communal land

so the witch hunt

expropriated women

from their bodies

which were thus ‘liberated’ from any impediment

preventing them to function as machines

for the production of labor

It was in the torture chambers

and on the stakes

on which the witches perished

that the bourgeois ideals

of womanhood and domesticity were forged

*

W. E. B. Du Bois, Black Reconstruction in America

White revolt against the domination

of the planters over the poor whites

was voiced by men who called for a class struggle

to destroy the planters

this was nullified by deep-rooted antagonism

to the Negro whether slave or free.

If black labor could be expelled from the United States

or eventually exterminated

then the fight against the planter could take place.

But the poor whites and their leaders

could not for a moment contemplate a fight

of united white and black labor

against the exploiters.

Indeed the natural leaders of the poor whites

the small farmer the merchant the professional man

the white mechanic and slave overseer

were bound to the planters

and repelled from the slaves

and even from the mass

of the white laborers in two ways:

first they constituted the police patrol

who could ride with planters

and now and then exercise unlimited force

upon a recalcitrant or runaway slaves

and then too there was always a chance

that they themselves might also become planters

by saving money by investment

by the power of good luck;

and the only heaven that attracted them

was the life of the great Southern planter.

*

Stefano Harney and Fred Moten, The Undercommons

They say we have too much debt.

We need better credit

more credit less spending.

They offer us credit repair

credit counseling

microcredit

personal financial planning.

They promise to match credit

and debt again

debt and credit.

But our debts stay bad.

We keep buying another song

another round.

It is not credit we seek

nor even debt

but bad debt

which is to say real debt

the debt that cannot be repaid

the debt at a distance

the debt without creditor

the black debt

the queer debt

the criminal debt.

Excessive debt

incalculable debt

debt for no reason

debt broken from credit

debt as its own principle.

*

Bernadette Mayer, Utopia

House and buildings

were left just as they were:

all doors are large

none are revolving

there are no cagelike places

elevators are transparent

all windows can open

places open out onto other places

hallways are generous

there is no rent

backyards behind city buildings

are joined without fences

so you could ride a horse

behind the streets

some pavements have turned back to dirt

there isn’t any money

money became so physically large

that to accumulate five dollars

it would take a whole old-fashioned

room full of these big metal things

ellipsoid in shape

all the sewage of the world

makes fuel plus a generous

contribution from the stars

the ex-oil companies take care of that

we clean the streets

the schools are an essay on schools

you can get what you need

from the stores and storehouses

if you act greedy no one will look at you

drugs are dispensed by old people

if you want dope

you have to go to the museum

when you die

there is no hospital

it’s safe to be born and safe to die at home

there’s no accidents

hideous things have ceased to befall you

various women and men

come to your house when you need them

to work against these things

often old people say

“I have never suffered pain”

*

Emanuele Coccia, The Life of Plants

Plants are the breath of all living beings

the world as breath

In turn any breath is evidence

of the fact that being in the world is

fundamentally an experience of immersion

To breathe means to be plunged

into a medium that penetrates us

in the same way and with the same intensity

as we penetrate it

Plants transform the Sun’s breath

its energy its light its rays

into the very bodies

that inhabit the planet

They make of the living flesh

of all terrestrial organs a solar matter

The Earth feeds off the sun

and constructs itself from its light

Plants metamorphose light

into an organic substance

and make life a primarily solar fact.

Every living being is only the effect

and expression of heliocentrism

on account of the fact that everything on Earth

exists thanks to the Sun.

__________________________________

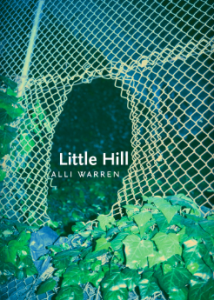

Little Hill by Alli Warren is available now via City Lights.

Alli Warren

Alli Warren's new book of poems is Little Hill (City Lights). She published her Poetry Center Book Award-winning debut, Here Come the Warm Jets, with City Lights in 2013. She is also the author of I Love It Though (Nightboat Books, 2017), as well as numerous chapbooks. She has edited the literary magazine Dreamboat, co-curated the (New) Reading Series at 21 Grand, co-edited the Poetic Labor Project, and contributed to SFMOMA's Open Space. Her writing has appeared in numerous publications, including Harpers, Poetry, The Brooklyn Rail, Best American Experimental Poetry, and BOMB. She has lived and worked in the Bay Area since 2005.