All the Books to Read While You’re Not Drinking During Dry January

Christiana Spens Recommends F. Scott Fitzgerald, Jesmyn Ward, and More

There is something comforting, in a drinking culture such as ours, to know that it won’t seem weird to avoid wines and spirits in favor of soft drinks when January comes around. Alongside Sober October, Dry January has become a socially acceptable time to abstain, and it always makes me realize just how extreme our drinking culture is that we need this schedule to feel ok about not wanting to drink. Having noticed this about myself last year, I began to realize how unconscious and automatic my habits had become, and how tied they were to relationships and social cues.

Taking inspiration from Soberish by Kayla Lyons, which promotes an attitude of ‘a more mindful relationship to alcohol’ and an awareness of how social drinking can enable unhealthy habits, I began abstaining and rethinking social relationships that were often entangled in addictive patterns of behavior.

To this end, I started reading more books about drinking and addiction, and rereading novels that had shaped my own ideas about them over the years. Having written at length about patterns of self-destruction and escapism in my book The Fear, I understood the repetitive patterns of drinking as a reaction to trauma and anxiety already—but I had underestimated the role of sociality and relationships in accentuating self-destructive behavior in the name of bonding. So follows a selection of books I have found enlightening in my own journey to a more soberish lifestyle—and better relationships.

*

I remember picking up a copy of Ottessa Moshfegh My Year of Rest and Relaxation at my friend’s flat in Glasgow, where I had escaped to for a weekend, as he read Nancy Mitford’s The Pursuit of Love. They were good companion pieces, and as I read Moshfegh’s novel that first time, the link between a desire for intimacy and a desire for drink (and pills), revealed itself to me quite darkly. While Moshfegh’s heroine is in one sense a total recluse, as she abstains from life itself for a year in order to reset after her mother’s death, she is accompanied by her loyal and masochistic best friend throughout this journey. In this entanglement, the deep self-delusion of addiction reveals itself, and how that is connected and at times enabled by co-dependence. And yet, the characters just want to be loved, however absurd the circumstances, and they do in their way.

In the classic 1980s novel, Bright Lights, Big City by Jay MacInerney, we meet another social creature dismayed by grief. I read it as a teenager and this line always resonated—“You keep thinking that with practice you will eventually get the knack of enjoying superficial encounters, that you will stop looking for the universal solvent, stop grieving. You will learn to compound happiness out of small increments of mindless pleasure.”

I took this novel as a kind of starting gun when I read it at fifteen, my father sick with cancer—but when I return now, I see so much that is newly, sadly familiar. Another line, he says: “You will have to go slowly. You will have to learn everything all over again.” And again, and again. And yet that realization is infectious and bonding; in reading this story, the common pain at the root of addiction is clarified, and that is the beginning of recovery.

On a similar note, it is always moving to read The Crack-Up by F. Scott Fitzgerald which was published in Esquire Magazine in 1936. A cautionary tale, if ever there was one, it opens thus:

Of course all life is a process of breaking down, but the blows that do the dramatic side of the work—the big sudden blows that come, or seem to come, from outside—the ones you remember and blame things on and, in moments of weakness, tell your friends about, don’t show their effect all at once. There is another sort of blow that comes from within—that you don’t feel until it’s too late to do anything about it, until you realize with finality that in some regard you will never be as good a man again. The first sort of breakage seems to happen quick—the second kind happens almost without your knowing it but is realized suddenly indeed.

It is in this context of personal crisis that Fitzgerald meditates on fame and addiction, and in particular the gradual freefall of his “cracking up” as he puts it, after years of a very social falling apart, in which he wrote The Great Gatsby, The Beautiful and Damned and This Side of Paradise. As the characters struggled with self-destructive drinking habits and one another, so did the author; in this essay, one of his last, he reveals the subtle ways his own breakdown made itself evident too late. Though he ends on a positive note, a decision to start over, it is sadly too late—Fitzgerald died at 44 from alcoholism, a few years before his wife Zelda died in a mental asylum that had caught fire.

At risk of seeming excessively gloomy, Anna Karenina by Leo Tolstoy always springs to mind when I think seriously about bad habits and personal responsibility. Following Anna as she becomes completely intoxicated first by Count Vronsky and then, as his interest in her wains, an opium habit, Tolstoy contrasts Anna’s trajectory with that of Kitty and Levin, who find in one another the means to build a happy marriage, a spiritual life, and a family.

Though Kitty felt rebuked by Vronsky when he first ignored her, ultimately hers and Levin’s life—of hard work, faith and family—is the better one. And yet, of course, I always loved Anna, and who cannot sympathize with her desire for romantic love, for passion, for excitement, even when such a life is impossibly unsustainable?

But this is the cautionary tale to end all cautionary tales, and as time goes on, I give less of my heart to Anna’s desperation, remembering how she abandons her own son in her stubborn need for rebellion and love in a society that won’t let her have it. Anna’s downfall is depicted as understandable, and she is deeply sympathetic, but Tolstoy also reveals the inescapable tragedy of her choices and the damage that her impossible desires thus cause. Always a humbling January read!

In some ways parallel to Tolstoy’s depiction of Kitty and Levin embracing the goodness of the countryside, Amy Liptrot’s memoir, The Outrun is a beautiful and uplifting account of recovery—this time as she returns to life in the remote Isle of Orkney after many lost years in London. Having also grown up in rural Scotland, this story always resonated with me, particularly the sense of needing to escape and then return home to a harsh but beautiful place.

This Ragged Grace by Octavia Bright is another brilliant memoir, out last year, which also recounts the twin journeys to family / home, and to sobriety. Charting the author’s impressive recovery from alcoholism as her father’s health deteriorates with dementia, this is another grounding, important story of choosing life and family, even when it is painful.

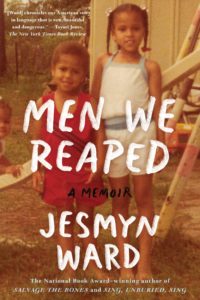

That said, family and home may also predetermine one’s downfall. In Men We Reaped by Jesmyn Ward, the author tells the story of her own hometown—DeLisle, Mississippi—and how the deaths of her brother and four other young men close to her are fated by the racism and trauma that the community has experienced. Addiction is a part of this, and it is important to understand, as Ward so elegantly reveals, the structural issues at the root of addiction and mental health problems, rather than necessarily any individual moral failing.

In Punch Me Up to The Gods by Brian Broome, the author also confronts the role of racism and trauma in developing addiction as a young Black man, and therefore the role of society at large to protect vulnerable young people, rather than to damn them further. In The Realm of Hungry Ghosts by Gabor Maté is a wonderful book about the psychology of addiction as rooted in trauma and attachment issues, and it provides an excellent context with which to better understand the interplay of environment and individual behaviours. In All About Love, meanwhile, bell hooks writes about forms of love, why “love and abuse cannot co-exist” and why ultimately “addiction makes love impossible.”

*

This is the tragedy I keep coming back to: that those who end up in the clutches of addiction most often simply want love, and relief from the pain of not having it. And yet, as bell hooks writes, and which seems evident from most of the books I’ve listed here, it is impossible to be fully present to another person if you are consumed by something else, or simply the fear of trusting and connecting to another person, even without a substance. The sad irony is that we use alcohol and other drugs to help us connect to each other—and it is encouraged by our culture—but it damages us.

I was at lunch with another writer recently, and we were talking about this—how with all substances, the desire at the root of taking them is for intimacy—to be with other people, and for a certain adventurous, escapist, joyful energy of connection. And if it is not for that reason, then it is to numb the pain of being unable to find that connection. We all seek attachment, basically, and especially if we have not received enough of it before; how tragic then, that we choose a poison that will eventually tear us apart from those we might love.

After we’d spoken, I remembered a poem another writer had read me once, that I have been thinking of ever since: Remembering Elaine’s by Frederick Seidel—it captures the draw and tragedy of social drinking better than anything I’ve read. If only we could remember each other, before we are gone, though—look out for each other, before we are gone. That is one kind of love, and it’s at least one to start the year on. It’s at least a good intention.

*

Further reading: Wishful Drinking by Carrie Fisher • Portrait of an Addict as a Young Man by Bill Clegg • Dry by Augusten Burroughs • Lit by Mary Carr • Drinking: A Love Story by Caroline Knapp • The Urge by Carl Fisher

Christiana Spens

Christiana Spens is the author of The Fear (2023), The Portrayal and Punishment of Terrorists in Western Media: Playing the Villain (Palgrave Macmillan, 2019) and Shooting Hipsters (Repeater, 2016). She holds a PhD in International Relations from the University of St. Andrews, and before that read Philosophy at Cambridge. Her writing and artwork has appeared in various publications including The Irish Times, Prospect, Glamour, Stylist, Dazed, the Quietus, The London Magazine, NYRB, and Studio International. She lives in London.