All Stories Float Ashore: Fae Myenne Ng on the Chinese Titanic Poet-Sailor Deportee

"Men of Exclusion held truth close, sailing like the wind into a port of safety."

When my seafaring father told me about the Chinese sailors who jumped from the Titanic, he added with vigor, “I’d have jumped too.”

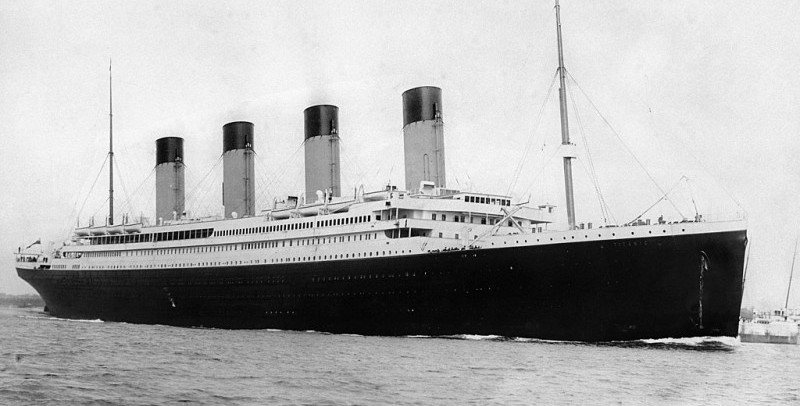

The two mariners who leapt into the icy Atlantic–a groom en route to his nuptials in Cleveland and his best man–perish, but their seventeen-year-old friend grabs hold of a plank and drifts; he’ll be the last man pulled out of the ocean. The survivor, Fong Wing Sun, gave us the iconic image of a man afloat, his likeness eventually altered to a woman’s form, the plank widened to a door, this image endlessly recycled for that film.

All 706 survivors are taken to New York on the rescue ship RMS Carpathia, but the six surviving Chinese are forbidden to disembark. America’s Exclusion Act was at full mast; at dawn the Chinese sailors are deported. Five vanish. Only Fong Wing Sun is tracked as working on Cuban banana ships. In 1920, he enters the States, possibly—as my own seaman Uncle did—by jumping ship.

He settles in the Midwest, works, and saves. At 50 he can afford to have a family and procures a wife from Hong Kong. The marriage doesn’t survive but he has children and though he lives to 90, he never reveals his sea story to his American-born sons. But he writes a poem and sends it home to family in Toishan, China.

When I found the poem online, I was thrilled but fearful that Dad was right; living in this Land of Barbarians, I’d abandoned my Chinese.

Exclusion created a new genre—the lie in America.

San Franciscan bred; Cantonese is my original tongue. I didn’t hear English till I entered Kindergarten; I also went to Chinese School where my love for poetry grew.

But now, my rusty Chinese is out to sea and I struggle, afloat in a darkness as if among ship debris.

The poem opens with a description of a ‘high’ sky and a ‘wide’ ocean; I feel the unreachable distance between the sea and the heavens. The line ends with a doubling of the character: churning, churning; I hear my childhood sound of distress: borh borh, I feel my tongue bouncing inside my mouth, touching its roof, skimming the base along my teeth, searching but not swallowing.

‘A plank of wood’, the next line begins, ending with: ‘Rescue/Life/I’.

Rescue’ is the poet’s plea.

‘Life’ is his hope.

‘I’ is the man buoyed.

‘Life’ is centered between the words, ‘rescue’, and ‘I’.

The sailor is coddled in the roiling ocean waves. A wooden plank offers camaraderie and our poet accepts.

Line three is a plea: Brothers, how many are left?

Laughter closes the poem: Tears dried, sorrow dissolved, death tricked, laughter arrived: ‘Ha. Ha.’

I have read to survive.

*

My father arrived in America in 1940 and found Exclusionary America as hostile as when Fong Wing Sun arrived in 1920. The Page Act (1875) had forbidden Chinese women. The 1882 Exclusion Law barred all other Chinese (the men!) and also made it illegal for them to own property, testify in court, vote, access education and most criminally, it damaged the procreation of the Chinese American family for over six decades. In 1870, the ratio of Chinese men to Chinese women was 13 to 1; in 1880 it was 21 men to a single woman, and until 1920, it wasn’t ever lower than 12 men to one woman. This, along with the anti-miscegenation laws which forbade intermarriage between Chinese and whites, not repealed in California till 1948, and not in the country when Virginia abolished it in 1967.

Dad raged about this calculated sexual imbalance: “America made sure no Chinese babies were born.”

Exclusion made secrecy a necessity in my Chinese America. Exclusion Men circumvented that law with fake identities, marriages, births, and deaths. Keeping the story untold is keeping the family safe. Tricksters in speech and act: Exclusion Men used word-play to baffle a cop, curse a judge; they never backed down from trouble.

Dad and other Exclusion fathers hollered about these atrocities and then they laughed. This taught me that life wouldn’t be easy but if you can laugh; you’ve survived.

There’s an astonishing scene in Fong’s village in China near the end of The Six, the documentary about the Chinese sailors on the Titanic. As the researcher casts about for sea stories of the shipwreck, Fong’s great nephew casually says, “He wrote it to us in his poem.”

Especially endearing to me is how this descendent recites the poem—not in the rhythmic chanting of a scholar but as a song the six-year-old heard in wonderment and committed to memory with delight.

Art survives.

Perhaps Fong believed his poem would do more work back home in China: Look at America. Know our American lives.

If he didn’t reveal his Titanic story to his American sons, it might have been for protection of family. The character ‘sun’ in his name means mountain. Iceberg is written powerfully in Chinese as ‘ice mountain’. When Fong Wing Sun sends his poem home; it sails, the mythic sea turtle swimming forever.

History prepared them to know that their future was suspect, so their silence had to be born in courage.

Dad also practiced holding stories in his belly. He taught me that the told story was dangerous. Silence is an act of protection.

But I hear Exclusion’s forbidden stories and recognize the kept truth and I write the books that Exclusion Men kept secret in their center. I tell the muted stories before they mutate. I believe our literature hasn’t caught up with this truth—Exclusion created a new genre—the lie in America.

*

Decades of writing in English drowned my Cantonese. Recently, I found my exercise books and as I looked at the complex brushstrokes, I’m baffled. Though I can still chant the poems by memory, I can barely read my own meticulous calligraphy. Who wrote these?

Yet, three poems remain in my mind like planks. I hold onto them for their united theme of loneliness: missing home, missing Mother, a returning Orphan Bachelor walking toward his village as children call out: Old Man, Old Man, where do you come from?

*

In life or death, all stories float ashore.

Poems of lament teach me that suffering has witness. Fong’s sailor-poem joins the lexicon of Exclusion Era poetry: the wooden fish songs chanted by barren Grass-Widows in China, pining for the husbands they’d known for a fortnight, the poetry carved on the walls of the barracks of Angel Island, where the Chinese were detained and interrogated from 1910-1940.

Detainees of Angel Island teach me: Protect your strengths in order to survive. My father was interned there in its last year of operation, one of the youngest detainees. When I was 16—Dad’s same age as an inmate—I visited the infamous island and stood in the barrack where he’d slept on the top of a three-tiered bunk. Walking by a thick beam, I saw a graffiti-like carving of our blood name—not the paper name he’d bought to circumvent Exclusion. When I asked Dad if he’d inscribed our name on the Island, he only smiled, “What do you think?”

Exclusion Men from the Island teach me to be daring. Hiding a paper name, evading deportation, sinking into the sea, all in China had been far more dire. History prepared them to know that their future was suspect, so their silence had to be born in courage. Men of Exclusion held truth close, sailing like the wind into a port of safety.

Long before the Poet jumped into the ocean, his luck had been meager and when desperate in the ocean, he’d practiced abundance in hope. Trouble will be endless, as wide as the ocean and all hope is cold. Make a friend of the dregs in the sea. Save your life and then laugh: Ha Ha.

As the deported poem returns to America, I think of Dad’s longevity tonic: Laughing three times invites another decade of vitality. Ha! Ha! Ha!

__________________________________

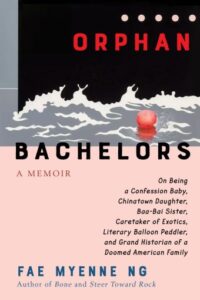

Orphan Bachelors by Fae Myenne Ng is available from Grove Press, an imprint of Grove Atlantic.

Fae Myenne Ng

Fae Myenne Ng is the author of bestseller and PEN/Faulkner Fiction finalist Bone and American Book Award winner Steer Toward Rock. Her work has been published in Harper’s Magazine, The New Republic, Ploughshares, and anthologized in Charlie Chan is Dead: An Anthology of Contemporary Asian American Fiction, Literature Across Cultures, The PEN Short Fiction Project, and The Pushcart Prize. She has been the recipient of fellowships from the American Academy of Arts & Letters, the Guggenheim, the Lannan Foundation, the NEA, the Radcliffe Institute, and the Rockefeller Foundation. She teaches creative writing and literature in UC Berkeley’s Department of Asian American and Asian Diaspora Studies.