All of Our Good—and All of Our Evil—Lies in Wait in the Archives

Deep in the Files with Margaret Atwood, Adrienne Celt, Wilkie Collins, A.S. Byatt, and More

From call transcripts to separate storage systems, from electronic classification to coded text messages, the impeachment proceedings have put archival practices squarely in the news. Or maybe they’ve always been there. Missing tax documents. Livestreams of police brutality. Body cameras. Photos of political candidates wearing blackface. Birth certificates. Alexa collecting your data. Hackers collecting your data. The NSA collecting your data. All these stories are about how we record events, and what happens to those records after. Which records get kept, and which get erased? Who makes that decision? What kinds of records are sufficient evidence for a triumph, a misstep. . . a crime?

I’ve always been into records. Growing up, I was obsessed with keeping all my letters, art projects, and spelling quizzes for historical posterity. Who knew when some future biographer might need the ten spiral-bound notebooks I filled with Spice Girls fanfic during fourth-grade journaling hour? (Listen, Beyoncé gets it.) It was probably inevitable that I would wind up in academia, which finally gave me an excuse to root around in dead people’s diaries “for research,” and equally inevitable that I would end up writing a novel, Take Me Apart, about an archivist using a trove of abandoned documents to uncover the truth about a photographer’s death.

The more time I spend in archives, the more I realize how important they are. Behind the impenetrable strings of call numbers, archives are a response to the all-too-human fear of being lost. But the process of preserving documents is inherently biased, from the systemic forces that prevent marginalized voices from being preserved, to the interpretative sway that historians have over the documents that have been kept. Archives raise essential questions about power, subjectivity, and collective memory.

No wonder they’re good fodder for fiction. Here, I’ve assembled some of my favorite novels about archives and documents: thrilling reads that turn seemingly dreary record-keeping into nail-biting suspense. These books might inspire you to open your cardboard boxes of childhood memorabilia for a trip down nostalgia lane—or they might make you want to burn everything you own and start over with a new identity. Either way, you’ll never look at your email’s “Archive” button the same way again.

Austin Clarke, The Polished Hoe

Archives are not egalitarian. Creating documents requires literacy, time, and access to writing materials; preserving those documents over time is even more expensive. And when it comes to institutional archives, deciding which documents are worth preserving involves a hugely subjective assessment of “historical significance.” This unbalanced system often excludes people of color, women, and other marginalized groups.

Austin Clarke’s novel The Polished Hoe illustrates these issues through the story of Mary-Mathilda, a black woman in 1950s Barbados who goes to the police to confess to murdering a white plantation owner. Over the course of the novel, as Mary-Mathilda narrates the traumas of her past to her childhood friend, a police sergeant, her confession becomes a testimony to the horrors of colonial rule, as well as a reflection on the limitations of recorded history. “These narratives are the only inheritances that poor people can hand down to their offsprings,” Mary-Mathilda explains. The Polished Hoe beautifully demonstrates oral history’s immense emotional power as well as its chronic devaluation by the law.

Margaret Atwood, Alias Grace

There is a surfeit of Margaret Atwood novels relevant to the topic of archives (the nested stories of The Blind Assassin, the famous epilogue to The Handmaid’s Tale), but Alias Grace is the one I can never stop thinking about. The novel is based on a real historical figure, Grace Marks, a maid who was convicted of murder in 1843 for the death of her employer and his housekeeper. (A male servant, who whom she allegedly conspired, was hanged for the crime.) Historians have never determined the extent of Marks’s involvement in the murders and Atwood steps right into that controversy, imagining Grace’s life from childhood through her conviction and imprisonment.

Atwood weaves real quotes from historical accounts and trial testimonies into the novel, but the richness of Atwood’s own prose allows us to see how stark and unsatisfying these documents are. The novel’s beauty comes from the imagination of what could never have been recorded: Grace’s desires, dreams, and fears; her interior life. The book’s description of Grace’s early years reveal the violence and indignity of life as a working-class woman in the 1840s; the sections set in the prison, where a male doctor is interviewing Grace for his research on criminal behavior, open up ever-relevant ethical questions about psychiatric treatment and incarceration. Class is as much of an issue here as gender: in one of my favorite scenes from the novel, Grace learns that the prison warden’s wife keeps scrapbooks of news clippings about female murderers, collecting tragedies like baseball cards.

Like many of the books on this list, Alias Grace raises important questions about whose versions of a story enter the historical record—and whose hold up in court.

A.S. Byatt, Possession

Like Umberto Eco’s The Name of the Rose, Possession is a classic of the “archival adventure” genre, and for good reason. This Booker prize-winning doorstopper-sized novel follows two academics, Roland Michell and Maud Bailey, as they uncover an illicit love affair between two nineteenth-century writers, Randolph Henry Ash and Christabel LaMotte. I’m endlessly impressed by the poems and letters “by” Ash and LaMotte, which are a near-perfect ventriloquism of 19th-century poetry. Some parts of the early 90s satire of academia are a little outdated, but the more human elements of Roland and Maud’s research journey—their self-consciousness, the way they use Ash and LaMotte as ciphers for their own feelings—are timeless.

In this novel, archives are crucial, thrilling, even passionate. But although the novel is unmistakably a love letter to research and reading, Byatt also acknowledges how easily historical records can be misinterpreted: a turn in the final chapter reveals how a single lost document can irrevocably alter the stories we tell about the past.

Marisha Pessl, Night Film

Night Film is set in the spooky, fantastical world of a fictional cult horror film director named Stanislas Cordova, whose films are so famously violent they’ve been banned from exhibition. When Cordova’s daughter turns up dead, investigative journalist Scott McGrath sets out to find the reclusive director, only to tumble into a labyrinth of fandom and rumor.

The book shows the reader the same newspaper articles, screenshots, and photographs that McGrath pores over; you can even go onto Pessl’s website and find an appendix of supplementary documents that aren’t included in the book. But although you get all the same clues McGrath does, this novel is less an armchair-detective novel and more an experience that sucks you down a vortex and spits you out at the end, blinking. I love the book’s illicit feel, which matches Cordova’s films, and how Pessl weaves the internet and new media into this story about super-analog, super-secret films.

Wilkie Collins, The Woman in White

In the past, I’ve encountered some resistance when recommending Wilkie Collins. Victorian novels aren’t everyone’s cup of tea, and the 1859 date on this book tends to provoke a little side-eye. But in the pleading voice of your friend who keeps dating bad people but has now finally found the one, let me say: Wilkie Collins is different.

Often called the inventor of the detective novel, Collins wrote some truly rollicking reads. The Moonstone is probably the more famous of his works, but The Woman in White is the one he considered his masterpiece, and I tend to agree. Everything in this book comes in doubles: two lovers, one with a secret doppelgänger, are being kept apart by two delightfully overdrawn villains. Ultimately, the lovers’ happiness hinges on when a particular event was entered into a parish register. Too bad such records are very susceptible to fire.

The Woman in White is full of Gothic sensationalism, genuine emotion, and some very funny asides. If you like the fake-found-document conceit, you’ll love The Woman in White, which collects a bunch of different characters’ versions of events into a “scrapbook” format. From amateur detectives to unreliable narrators to surprising twists, The Woman in White has many features of a 2019 bestseller. . .a hundred and sixty years ahead of schedule.

Maria Semple, Where’d You Go, Bernadette?

Novels told through emails feel like one of those technical challenges on The Great British Baking Show—they sound delicious in theory, but half end up oozing too much expository information, and most of the rest are raw dough under a layer of awkward internet slang. Only one hits that perfect balance. This week’s star baker is Maria Semple, for Where’d You Go, Bernadette?

Technically, emails are only some of the documents in this epistolary novel, which also features school forms, neighborhood announcements, and diary entries, and more. Most of these documents come from the family and enemies of an agoraphobic Seattle woman named Bernadette Fox. When Bernadette suddenly disappears, her teenage daughter, Bee, sets out on a mission to find her mother at any cost.

Do yourself a favor and read this shiny burst of a novel before you see the movie adaptation. Nothing against the movie adaptation (it has Cate Blanchett!), but the book is so perfect and hilarious that it deserves the first crack at your laughs. Although it’s much more comedic than any other book on this list, it has immense emotional depth and tackles many of the same questions about evidence and accountability—just with a lot more mudslides.

Caite Dolan-Leach, Dead Letters

When Ava learns that her estranged twin sister, Zelda, is dead, she goes back to their family home in upstate New York for the funeral. But a strange trail of clues and letters, seemingly from beyond the grave, make Ava start to question whether her sister really died, or whether this is just another one of Zelda’s practical jokes.

The book is packed with clever shoutouts to the Oulipo movement, but its emotional core is the relationship between Ava and Zelda. The back-and-forth between Ava’s narration and Zelda’s letters fleshes out a complex story of sibling rivalry and love. As in Where’d You Go, Bernadette?, the interpreter of the documents is someone close to the person who created them, and Dolan-Leach explores how that prior relationship influences the interpretation of the documents. Zelda carefully curates her missives (you won’t understand the full extent of the curation until the end), but as soon as they are passed over to her twin’s analytical eye, the narrative swells out of Zelda’s control. This investigation into family secrets also becomes a testament to the dangers of being misread.

José Saramago, All the Names

All the Names follows a clerk, Senhor Jos, who works in the municipal archive of Births, Marriages, and Deaths in an unnamed city. In his spare time, he curates a secret collection of news clippings about famous people, a project that seems mostly harmless until he begins stealing their personal records from work so that he can copy them into his own files. One day, he accidentally takes home an unknown woman’s record and becomes obsessed with learning as much as he can about her life.

Saramago’s prose is always captivating: lyrical yet plain, suffused with gentleness, and fluidly recreated by his longtime translator, Margaret Jull Costa. Reviewers often describe this novel with words like “sweet” or “magical,” which I think overlooks the challenging issues of stalking and obsession that undergird the book. What happens when the record-keeper, often presumed to be a neutral part of the archive’s machinery, becomes personally involved? What traces of us enter official record, and what might they tell a stranger about our lives?

Adrienne Celt, Invitation to a Bonfire

Adrienne Celt’s second novel, loosely based on the marriage of Vladimir and Vera Nabokov, is presented as an assemblage of letters, diaries, and news clippings. It moves between the perspectives of three Russian expats living in New Jersey in the late 1920s: the famous writer Lev; his wife, Vera; and a young woman, Zoya, who works at the private school where Lev has recently begun teaching. We learn at the beginning of the novel that Lev was murdered in 1931 and that Zoya died the same year, and the rest of the book charts the dark, surprising events leading up to their deaths. Writing a novel told partly from the perspective of a Nabokov stand-in is an ambitious project, to say the least, but Celt succeeds, both in the dark beauty of her prose and in the way the narrator openly toys with the reader.

A foreword to the book introduces Zoya’s diary as part of a “collection of papers” willed to the school after Vera’s death, so even though Zoya writes her diary planning to burn it, we already know that she won’t. Perhaps this is what is so comforting about fictional representations of archives, even at their darkest moments. They show us stories that wouldn’t have been recorded, documents that would have been destroyed. It’s reassuring to step inside a world that’s been assembled for us, where we can see the whole archive—and decide what it means.

__________________________________

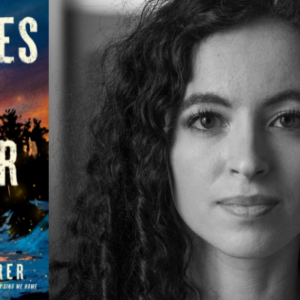

Sara Sligar’s Take Me Apart will be out in April, 2020 from FSG.

Sara Sligar

Sara Sligar is an author and academic based in Los Angeles, where she is a postdoctoral fellow at the University of Southern California. Her debut novel is Take Me Apart.