Ahead of Their Time: A Reading List of Nonconformist Women

From Sylvia Townsend Warner to Annie Proulx

I have never forgotten the first time that I saw A Doll’s House by Ibsen. I was 22, I had never read the play, and I had no idea of the plot. When, in the last act, the babyish Nora finally realises that her pleasant life is actually one of coddled subjugation, and roars, “I have a duty TO MYSELF!” before walking out on her astonished husband and slamming the door behind her, I couldn’t believe what I was seeing. I felt as if I’d had a bucket of ice-water thrown in my face—it was astonishing, invigorating and unforgettable. In my recent novel, Old Baggage, I wrote about a former suffragette, Mattie Simpkin, a woman who has never conformed—a woman who scarcely knows what conformity is—and as I explored Mattie’s world, I felt the same blast of energizing joy that Nora’s epiphany had given to me.

The novels I’ve chosen all evoke aspects of that feeling: they all feature women (and in one case a small girl) from other eras who don’t do what they’re supposed to do—women who have decided to grab the tiller and steer the course of their own lives. Every one of them makes me want to stand up and cheer.

Lolly Willowes, Sylvia Townsend Warner

Lolly Willowes, Sylvia Townsend Warner

This is an extraordinary book. Lolly, a maiden aunt, has always been dependent: first on her father, then on her brother and his family. She is middle-aged, unremarkable, loved in a low-key way, but also taken for granted. And then, one autumn, Lolly finds that a different life is calling to her; she consolidates her small savings, moves to a cottage in the country, acquires a cat and becomes a witch (yes, you read that last sentence correctly). Hers is not the spell-based magic of Harry Potter’s world, but that of a woman finding a subversive and hidden part of herself and glorying in the discovery. All women are witches, says Lolly, even “if they never do anything with their witchcraft, they know it’s there—ready!”

Anita and Me, Meera Syal

Anita and Me, Meera Syal

Semi-autobiographical, and set at the start of the 1970s, this novel is narrated by nine-year-old Meena, daughter of Punjabi immigrants, and the only non-white child in a working-class village in the industrial English Midlands. She is perceptive and critical, not only of the narrow lives and prejudices of her neighbours, but of the eccentricities of her own, highly-educated parents. Caught between two cultures, and with no one to follow, she squares her shoulders and chooses a route of her own. The author is not just a superb writer, but an actor and comedian, and the book is shot through with her sharp wit.

High Wages, Dorothy Whipple

High Wages, Dorothy Whipple

Jane Carter is a shopgirl in a town in the north of England in the years prior to the First World War. She has no money but she is astute, ambitious, and a fast learner, and she knows her own worth. Defying snobbery and class, she takes a daring leap and opens a dress shop of her own. This is a rags-to-riches story, but rooted completely in real life; Dorothy Whipple wrote eight novels and they are all utterly gripping, her characters presented with extraordinary insight and sympathy, her plots always domestic, but never taking a predictable course. And Jane Carter is the finest of heroines.

The Shipping News, Annie Proulx

The Shipping News, Annie Proulx

Agnis Hamm, known throughout most of the book as The Aunt, is not the main character in this novel, but instead the steady sidekick, the battery that drives the plot. Born into poverty in Newfoundland and suffering an unspeakable childhood, she has carved out a life in which she has made all her own choices, finding both a skilled career and true love. When her adored partner dies, The Aunt decides to return to the place where she spent her childhood, taking her nephew and his broken family with her. She is dry, fierce and magnificent, and is one of my favourite characters in 20th century fiction.

Main Street, Sinclair Lewis

Main Street, Sinclair Lewis

It’s 1912, and Carol Kennicott, a city girl bursting with high ideals, marries for love and goes to live in a small town, where the opinions of the inhabitants are as narrow and dusty as the main street. Her brave attempts to introduce tolerance, beauty, and progressive views to the smug middle classes of Gopher Prairie are both funny and painful (“They were staggered to learn that a real tangible person, living in Minnesota, could apparently believe that illegitimate children do not bear any special and guaranteed form of curse, that some poets do not have long hair; and that Jews are not always peddlers or pants-makers”). She is patronized and dismissed and she discovers that there is sometimes cruelty behind the smugness. Only when she leaves and finds independence and a job in the city can she achieve a perspective on the small world she has left behind.

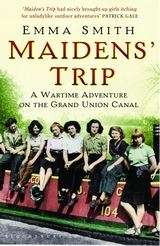

Maiden’s Trip, Emma Smith

Maiden’s Trip, Emma Smith

The author was very young when she wrote this novel, and the experiences on which it was based were only just behind her; as part of a female crew of three, and after the briefest of training, she piloted a narrow boat along the wartime canals of England, delivering steel to the Midlands, and bringing coal back to London again. The job was skilled and physically tough, the girls were entirely unsupervised, and they were wholly aware of their extraordinary freedom and independence. Most of their friends were in the forces, being shouted at or fired upon; Emma and her companions were in charge of their own little world. The book has the freshness of an April breeze, full of grit and blossom.

Lissa Evans

Lissa Evans has written books for both adults and children, including Their Finest Hour and a Half, which was longlisted for the Orange Prize. Crooked Heart was also longlisted for the Baileys Women's Prize for Fiction (formerly known as the Orange Prize); it is her first novel to be published in the US. Evans lives in London with her family.