On the morning of my flight to San Francisco last February, I sent Alex a video clip panning the snow-dusted sidewalk outside my apartment in Manhattan. Shuffling towards the subway, the wheels of my rolling suitcase leaving a trail of parallel lines in my path, I felt my phone vibrate in my pocket. “This is what’s waiting for you,” Alex replied, snapping a photo from atop Dolores Park: the Pacific blue sky above, the city bathed in dazzling sunlight below.

During the flight, I tried reading but couldn’t concentrate. The words kept scrambling in and out of focus. Eventually, I gave up and resigned myself to sitting listlessly, not even bothering to recline my seat even though the row behind me was empty, this being the height of the pandemic. With sour coffee breath recycling in my mask, I focused instead on the tiny airplane inching across the screen in front of me, bending an arc across America, and thought: This is so absurd. It wasn’t supposed to be like this.

In an alternate reality, I would have been flying cross-country this weekend for Anthony’s 29th birthday and meeting Alex Torres, his partner of seven years, for the first time. The three of us would have had so much fun together: gossiping about the latest drama going down in the subtweets of our mutual nemeses, waiting on the edibles to kick in, deciding on which underground sex party to attend, wandering the streets together as they showed me the city through their eyes.

“Would have, would have. The dead dwell in the conditional tense of the unreal.” Sigrid Nunez, The Friend. But in the simple past tense of the real, none of that happened. I landed at SFO two days before Ant’s birthday, seventy-two days after his death. “What’s the difference between birth and death, anyway? Aren’t they just the opening and closing of worlds?” Anthony So, Afterparties.

Why I went to San Francisco is still unclear to me. To commemorate Anthony’s life, to support Alex, to find closure? None of those excuses rings entirely true, especially not the latter.

Since meeting each other at the Lambda Literary Writer’s Retreat in 2019, I had been smitten with my newfound friend. Or perhaps “friend” isn’t the right word, too limiting and casual in its connotation. Although I can’t speak for Anthony, I know the way I felt about him existed somewhere beyond the bounds of friendship, in that liminal space between the platonic and romantic. In my mind, our relationship hewed closely to a model of friendship Michel Foucault described in a 1981 interview with the French magazine Gai Pied as “formless,” one in which queer men “face each other without terms or convenient words, with nothing to assure them about the meaning of the movement that carries them toward each other.”

I don’t know why Anthony befriended me, but I know that no one has ever made me feel as special to be in his orbit. I loved Anthony. Of that I am sure. Why I never told him? What that meant, what it means. Of that I’m less so.

“The thing is, even now, I still can’t say for certain whether I was in love with him.” Nunez again, on her departed friend. “Well, what does it matter now. Who can say. What is love?”

*

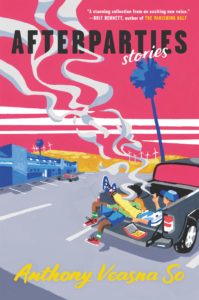

The first thing I noticed in Alex’s one-bedroom apartment in the Mission, besides the sparse furniture—since, for obvious reasons, he’d recently moved out of the home he shared with Anthony—was the advance reading copy of Anthony’s debut short story collection Afterparties on the shelf. “Take it,” Alex said, noticing me eyeing the cover, a vibrant explosion of hot pink sky and golden yellow horizon drawn by Khmer artist Monnyreak Ket. In the illustration’s foreground, two lovers—friends?—are reposed in the back of a truck in an abandoned parking lot, one’s legs resting languidly across the other’s lap, a plume of smoke rising from a joint, an open box of donuts beside them. Though I realize art is merely a representation of life, whenever I look at that drawing, I see Anthony and Alex lying together.

Beneath the blurb on the back cover, I was struck by the sudden shift to past tense in the author bio. “Anthony Veasna So (1992-2020) was a graduate of Stanford University… Born and raised in Stockton, California, he lived in San Francisco.”

Was. Lived.

I wanted to ask Alex, “Is the past always this jarring?” but didn’t, unsure of how to broach the topic. Having technically met fifteen minutes prior, Alex and I were still figuring out how to be around each other, how to grieve in the presence of a stranger, how to forge a friendship fated by tragedy. Rather than address Anthony’s glaring absence in the room, I skimmed through the stories I’d only partially read when he sent me a PDF of the manuscript some months prior. In them, I could hear Anthony’s voice so clearly; it leapt off every page.

I don’t know why Anthony befriended me, but I know that no one has ever made me feel as special to be in his orbit. I loved Anthony. Of that I am sure. Why I never told him? What that meant, what it means. Of that I’m less so.Seeing his stories in print, feeling the book’s weight in my hands, I was overwhelmed with gratitude. Not only for this gift he left behind, but for the honor of knowing him, however briefly. His writing allowed me to escape the present and resume our conversation where we’d left off, transporting me to that first week of December. Back to the Monday night we spent texting about the readings for our online course on Susan Sontag he convinced me to take. Back before I found out on Tuesday that—inexplicably—he was gone.

“Did the editor let you keep the bit about ketamine?” I asked his ghost, and he guided me to the exact page in “Human Development,” one of my favorite stories in the collection, where the narrator, also named Anthony, drunkenly berates his fellow Stanford alums at a cookout.

“When my former classmate began reciting the first sentence of [Hannah Arendt’s] The Human Condition,” he writes, “I muttered something about needing ketamine to dissociate from his very existence, then returned to the couch and scrolled through Grindr, blocking the profiles of every kickball player who was at the party.”

That line always makes me laugh, even though in that moment it provoked a feeling I can only describe as reader’s vertigo: the narrator blending with author, the text merging with a memory of our text messages.

He’s not really gone, I thought, with something between comfort and despair. He’s still very much alive on the page.

*

Although, of course, I didn’t know it then, the last time I would see Anthony in person was exactly one year before this trip, in February 2020. He’d come to New York to finalize his two-book deal with Ecco, and we celebrated by going to this seedy club in the Lower East Side named, conspicuously, The Cock. After meeting some friends at the bar upstairs, we descended into the infamous darkroom in the basement, vanishing into a sea of sweaty bodies, groping hands, and hard cocks.

An hour or so later, our need for ephemeral connection satiated, I found Anthony upstairs leaning against a wall, his face glowing in the blue light of his phone. “Wanna split?” I asked. Then without saying goodbye to anyone, I followed him out into the bitter cold on Second Avenue and hailed a cab back to my apartment uptown.

That line always makes me laugh, even though in that moment it provoked a feeling I can only describe as reader’s vertigo: the narrator blending with author, the text merging with a memory of our text messages.I can’t remember any of the men at The Cock that night—the individual details blur into a mosaic of sensory impressions. But I do remember laughing and swapping stories about our exploits during the ride home. And talking about books and movies and love until the sun crept through my window. And Ant sneezing and coughing uncontrollably on my rooftop as I chain smoked and taunted him for being “frail.”

Buzzed off the energy pulsing through the night air, I’d never felt happier. Anthony was on the verge of becoming a famous writer, and I couldn’t wait to witness his rise to stardom. Covid-19 still felt like a distant threat, brewing somewhere in the background. We might have only mentioned it in passing. The future unfurled before us, sparkling with possibility. From my rooftop, we seemed invincible.

Back inside, I recall thinking about his return flight the next morning with sadness, wishing the night would never end. I didn’t want to say goodbye.

*

According to Anthony, Sigrid Nunez’s 2018 National Book Award-winner The Friend was as close to “flawless” as any novel ever written. I had never read any Nunez, but I trusted Anthony’s taste in literature—in everything, really. That we loved the same books and hated the same writers was part of the reason we bonded. That, and the fact that we both loved a good party.

“Pisces but wanna dance,” his Twitter profile says. I wonder if his account will eventually get purged from the platform. Every now and then I check, half expecting a status update from beyond the grave. I imagine him spending hours drafting some irreverent joke like: “Keeping the peace in RIP since 2020” or “The afterlife… Beats the hell out of living.” But every time, I’m met with the same picture of a moustache accentuating his sly smile like a circumflex, the same look that says: It’s not that serious.

Anthony was on the verge of becoming a famous writer, and I couldn’t wait to witness his rise to stardom. Covid-19 still felt like a distant threat, brewing somewhere in the background.When I told Anthony a friend of mine committed suicide last summer, he immediately recommended The Friend. He had read the novel in the wake of his own friend’s suicide during their MFA program at Syracuse. Though he never explicitly stated as much, I got the impression he was urging me to find the story hidden beneath the surface of my grief, as if crafting a beautiful narrative would make all the pain worth it.

In The Friend, the unnamed narrator is a writer dealing with the suicide of her best friend, a fellow writer perhaps more famous for his reputation as a serial philanderer than as a novelist. Written in the second person, like an extended love letter to the deceased, the narrator muses on the vexed relationship between art, life, loss, and the loyalty of dogs to their human companions. Nunez’s metafictional prose style reminds me of Anthony’s: intimate and unadorned, affecting yet never overly sentimental. Here, and in her follow up What Are You Going Through (2020), the process of writing and the work of mourning are inextricably linked; in each book, the writer is both mourner and mourned.

The Friend opens with a page-length description of a curious psychosomatic phenomenon afflicting Cambodian refugee women in California in the 1980s. After surviving the horrors of the Khmer Rouge genocide, many of the women reported sudden blindness or blurred vision. However, doctors found nothing wrong with their eyes, and some suspected them of malingering.

“Seventy percent of the women had their immediate family killed before their eyes,” one psychologist is quoted in a 1989 article in the Los Angeles Times. “So their minds simply closed down, and they refused to see anymore—refused to see any more death, any more torture, any more rape, any more starvation.”

“One woman,” Nunez notes, “who never again saw her husband and three children after soldiers came and took them away, said that she lost her sight after having cried every day for four years.”

Anthony, the son of Cambodian refugees born in California, came of age with the legacy of such generational trauma looming. Though I don’t know if any women in his family had similarly experienced the onset of blindness, I’m sure he grew up hearing these stories. There are women in Afterparties who certainly fit this profile, like the mother in “Maly, Maly, Maly,” who died “pointlessly” by suicide: “an immigrant woman who just couldn’t beat her memories of the genocide, a single mom who looked to the next day, and the day after that, only to see more suffering.”

Nunez’s metafictional prose style reminds me of Anthony’s: intimate and unadorned, affecting yet never overly sentimental.And yet, in writing and life, Anthony had a way of couching unthinkable horrors in humor. One might call this style “traumedy,” which in the hands of a lesser talent could go terribly wrong, but Anthony pulled it off brilliantly. Despite facing generational trauma, poverty, forced migration, and racism, his characters’ lives are filled with laughter and joy. This mix of joy and pain is particularly poignant in the stories of the first generation, the children of the genocide born in California, like Maly and Ves in “Maly, Maly, Maly,” or Maly’s “boytoy” Rithy, who reappears as the star of his own story in “The Monks.”

But perhaps this rare combination of youthful exuberance and wry humor is best illustrated in “We Would’ve Been Princes,” a hilarious romp through the afterparty of a lavish Cambodian wedding. Here, the writing is irresistibly indulgent: from Mariah Carey on the jukebox to pilfered bottles of Hennessy to a famous pot-smoking singer from Phnom Penh with “fake eyelashes batting a mini hurricane”—the type of detail that lingers in the mind long after the story ends. There’s a tenderness here, too, a longing for connection that runs through all his stories. “For a brief moment,” the omniscient narrator at the party tells us, “the cousins… were again a bunch of kids, a brand new generation in a strange country, still learning what it means to be Cambodian.”

The push and pull of home, as refuge and cage, is another thread woven through Afterparties. The shifting allegiances and competing loyalties to communities at odds with one another create a significant amount of conflict for the characters. In “Baby Yeah,” an essay published posthumously in the journal n+1 about his friend’s suicide, Anthony offers some personal insight into this search for belonging so apparent in his fiction. “I knew something about isolation and estrangement,” he writes, “from both the outer world and my insular community of Khmer Rouge genocide survivors and their children, none of them particularly empathetic to my queerness.”

Throughout the collection, his characters grapple with guilt over their indebtedness to parents and grandparents, while at the same time recognizing how their families hinder their personal growth and happiness. In “The Shop,” Toby toils away in his father’s auto-repair shop after graduating college, yearning for some sense of direction. He frets over how his queerness excludes him from the ideal of “Cambo men,” while escaping at every opportunity to hook up with Paul, a relationship he hides from his family. More than anything, it seems, Toby craves freedom:

I remembered being younger and how I so desperately wanted to rush away from the valley where my parents had been dumped, gripping whatever promise I had in my fists. Real Possibility, I had convinced myself, existed in the big cities on TV, metropolitan areas where Real Life unfolded, where I could be as gay as I needed to be.

Afterparties took me on a wild ride through the peaks and valleys of human experience and left me feeling wonderfully unmoored. On the one hand, the stories are situated firmly—urgently—in the present. On the other, they are haunted not only by the past—the intertwined histories of Cambodia and California—but also by a phantom desire for connection in an increasingly fragmented world. And yet, these are not cautionary tales; flickers of hope abound. Whether through his use of the first-person plural in “Superking Son Scores Again,” or his uncanny ability to inhabit the lives of multiple characters—ranging from disaffected teenagers in “Three Women of Chuck’s Donuts” to a beleaguered nurse tormented by dreams of her dead aunt in “Somaly Serey, Serey Somaly”—Anthony’s expansive worldview and generosity of spirit is on full display.

The push and pull of home, as refuge and cage, is another thread woven through Afterparties.In the same n+1 essay, Anthony touched on the literary ambitions he shared with his dead friend: namely, their desire to be seen, as “misunderstood prophets” and “critics of our cultural moment” who “yearned to write masterpieces, timeless works infused with nihilistic joy and dissenting imaginations.” In this stunning debut—as much a critical contribution to contemporary queer literature as a loving tribute to his community of Cambodian Americans—Anthony did just that.

*

Though I’m loath to use this word, my weekend in San Francisco with Alex was nothing if not surreal. We walked for hours each day, visiting Ant’s old haunts, as Alex, ever the kind-hearted tour guide, told me stories about their life together. “Here’s where he proposed,” Alex said, gesturing toward The Eagle, a leather bar shuttered long before lockdown. Nearby, the city had memorialized parts of the SOMA neighborhood with plaques for the “Leather and LGBTQ Cultural District,” preempting the disappearance of queer spaces while also paying homage—cynically, in my view—to their importance in San Francisco’s history. It’s too late now, I thought. If only I had come sooner…

After hiking through Golden Gate Park, Alex pointed out the high school where Anthony had taught between graduating Stanford and starting his MFA. Immediately, I recognized it as the inspiration for the school in “Human Development” where the caustic narrator teaches “rich kids with fake Adderall prescriptions how to be ‘socially conscious’.” The character has a two-year contract under the title “Frank Chin Endowed Teaching Fellow for Diversity”—a satirical nod to another literary iconoclast and pioneer of Asian American theater.

Walking towards the Muni one afternoon, I remarked on how empty the streets looked compared to the last time I visited years ago. “It’s kind of nice with all the tech bros gone,” Alex replied. I agreed but nonetheless found the city eerie and apocalyptic.

All weekend I kept hearing Anthony’s voice in my head and wondered if Alex heard it, too. At several points during our daily strolls, I wanted to apologize for being so inept at providing any kind of emotional support, for never knowing the right thing to say. But I mostly listened to Alex’s stories, and when he ran out of things to say, I sat with him in silence. The two of us lost in a fog of reminiscence.

*

Paradoxically, the more I write about Anthony, the more I feel him slip away. Like the narrator in The Friend, I worry that telling a story about our relationship—however brief or intense or intimate—somehow cheapens it. That the narrative pushes me further from the truth. “You can’t explain death,” Nunez argues. “And love deserves more than that.” But that line from Anthony’s final story, “Generational Differences,” echoes in my head like an urgent plea: “We can’t let your history become lost in time.”

I’m embarrassed to admit that I haven’t read the last page of that last story. Not because I don’t want to know how it ends; I simply can’t bring myself to do it. Turning the page, then facing that great empty silence—it all feels too final, too tinged with grief.

In this stunning debut—as much a critical contribution to contemporary queer literature as a loving tribute to his community of Cambodian Americans—Anthony did just that.Finishing Afterparties triggers the same sinking feeling I get when leaving an afterparty. A part of me knows the night won’t last forever, that outside this smoky basement the sun is rising, and the thought of facing the piercing light of dawn fills me with dread. I know tomorrow is Monday, and once I get home the thrum of bass ringing in my ears will congeal into a migraine. That once the drugs wear off, the comedown will be brutal. So I stay and dance one more song.

But what happens after the afterparty? Where does one go from there? How do I close the book and move on with my day in a world in which my friend no longer exists?

Rather than search for answers, I prefer to remain in this transient space, the gap between pages, where my disbelief is suspended in the unfinished narrative. Maybe this impulse is indicative of some deeper delusion, a refusal to face reality bordering on the pathological, what Freud would call “melancholia.” Or maybe it’s a perfectly normal response to the shock of losing someone you love.

Whatever stage of grief this is, I don’t want the story to end. I’m not ready to turn the page and leave the afterparty. Not ready to let go.

__________________________________

Afterparties: Stories by Anthony Veasna So is available now from Ecco Press.