Once he knew she’d do it, he put his foot down and drove his father’s car through narrow roads, fielded on each side. She saw the house by a long green sweep of the headlands.

He parked between a tractor and an ancient box-shaped car. As he turned the headlamps off she caught a gleam of chrome and of dark leather seats. Birds flapped from the windows of the car. Hens. Her mouth opened to cry – the whiskey she’d drunk fumed in her throat.

She would recall that night often.

The house was dark, it had long passed midnight, yet the boy made no effort to be quiet. It seemed to her he made a great deal of noise – banging the car door, jangling the coins in his pockets – as though to advertise their presence. He had told her, whispered in her ear, the house was his Uncle’s but he had the run of it; he was the favourite Nephew. When the Uncle died the house would be his and the Uncle was very old now and frail. He walked across the yard and into a thicker fold of black; the tips of his boots scraped stone.

She could just see the white in his shirt. All the old ones had been dying lately, he said; sometimes it happened like that. He returned with a large ornate key which he held up in front of her face. She smelt soil, rust.

It occurred to her to be frightened of the boy and of the dark house and of the man inside. She would not know her way back to the holiday home, she had paid no attention at all to the route. She shivered, rubbing at her bare upper arms. When he took her hand she allowed herself to be led under the low hood of the porch but she did not return his pressure. The key rattled in the lock. Then, she felt him bend towards her. The dark concealed his expression but she smelt the drink-clouds on his breath and her heartbeat altered, he was so still. It seemed he might . . . His arm was along her waist. He was humming. Mock-solemnly, he kissed her hands. She was back in the centre of the yard. The boy hummed a tune the band had played in the dance hall and swung her round so the skirt of her dress lifted up above her knees and floated in their breeze. He breathed into her hair, clucking like a hen, his breath and hands very warm, till she laughed and became easy with him again.

The door opened into a kitchen lit by the faint red lamp of the Sacred Heart and the remains of a fire burning down into a grate. A dog stretched ragged, pink-tinged limbs for a moment but did not rise. She watched as the boy blessed himself rapidly at the font. Then, smiling, she blessed herself too. The water from the font dripped from her forehead on to her dress. The boy led her through the tall kitchen furniture, and, holding hands, they tiptoed up the stairs.

Halfway up the house, behind a thickly painted door, a man snored loudly – climbing and descending scales. She heard the sound of a body turning over heavily on springs. And it did not seem to her to be the frail turn of an old man. The boy tugged on her hand. When she did not move he began to whisper in her ear. Then she felt his mouth on her, large and wet. She felt his stubble burn on her chin as he half lifted her up the next stair. They continued up through the house. She heard behind them, the Uncle’s deep ascending snore.

The room had belonged to his Maiden Aunts. He let her in first, pinching her as she passed.

She said she could smell old ladies: damp, lemon and mothball, a faint tang of disinfectant. She said, wasn’t it terrible to end up all smelling the same? He patted the wall for the light switch. The light – a low, bare bulb – blinked twice, then, it seemed to her, swung into light. It lit the dead centre of the room. Thick yellow dust drew back across the floor. The room was barely furnished: two stripped, single beds, two tall glass book cabinets, a square iron chest. Two armchairs sat in shadows along the wall. She asked about the Maiden Aunts. He said they’d died the year before. She said, walking in, pointing out tracks on the lino, wasn’t it terrible to be old and make the same journey every day? She said she wasn’t looking forward to it. She asked—He said it was a long story. He would tell her more about them in the morning. They could do all the talking in the morning. She had to be quiet now as the Uncle would hear. He patted a bed and sat down to unlace his boots. The bed let out a tiny hiss of air. He allowed the boots to drop heavily onto the floor. There were no sheets or pillowcases, he said, they’d have to make do.

Slowly, she began to undo the buttons on her dress. The boy walked over to the iron chest and pulled back the lid. Her fingers trembled on the buttonholes. She watched as he lifted out a blanket. When he came towards her she said, very quickly, pointing out stains on the mattress, your Uncle’s generous with his room. Do you take all the girls here? He threw her a side of blanket to tuck in but he did not smile. She pulled her dress up over her head. He was in the bed, watching her in her underwear. She tugged the ribbon out of her hair. Under the hard light she felt – exposed and would have turned it off but it seemed . . . after the way they’d been together in the car. A creak on the staircase decided it for her. She was in the bed with him. He was laughing at her: did she think it was his bad old Uncle . . . listening ? Still smiling, he climbed on top of her. The bed creaked. It seemed to her it creaked out of time with their movements. It was not like the promise of it in the dance hall or in the car. In the car, it was warm from the heater and their quick breathing. The radio played green and yellow on their skin. He said—

She heard but she could not retain his words. He snapped something at her and then fell heavily on top of her, asleep. It was as though he’d struck her and then been struck unconscious himself. The whole of his weight pushed into her collarbone. One of his hands lay tangled in her hair. She lay under him, stunned. What was it that he’d said? She began to cry. She heaved him over and sat up and looked at the four corners of the room, the four, blurring, yellow mounds of dust, and back at the boy in the bed. Dust tumbled across the floor. And she was on the other bed, unable to suppress her noise and then unable to believe she was the one making the noise. Perhaps she had drunk more than she’d thought? When she raised her head, it was to the sounds of his whistling snores. Her eyes ached. Her hands and feet were frozen. Shivering, she went over to the chest. The blanket she pulled out was damp and so heavy, as though it could break her under its weight. She was lowering the lid of the chest down when she caught a flicker of green-white: a deep pile of linen sheets, pillowcases with lace edgings; her fingers felt along raised, embroidered writing. So, she was not good enough for sheets. She looked over at him, at the side of his long hair, the top of his shoulder, the spread of him under the rough blanket, and felt a spuming hatred. She slammed the lid of the chest down, but he did not wake.

She would recall that night often. What was it that he’d said? She did not sleep. She listened to the boy’s snores and, from the room below, the snores of the Uncle. She tried to turn the light off but the connection with the switch had snapped. All night the light burned. At one time she stood up for a book from the glass cabinets but found them both locked. The small glass panes were smudged with fingerprints. At another time she stood at the window watching the light change the colour of his father’s car, the rusty scales of the tractor, the glittering chrome and brass and mirrors of the Uncle’s car, the road and hills outside and beyond them a line of mountains coming out of the mist. At last she heard doors opening and closing, the rattle of a tin bucket. A close morning cough. She saw two black hens race across the yard, a shine holding on to their backs. Dressed, she lay on the bed with her hands folded neatly on her lap, waiting for him to wake.

They sat at the breakfast table. He played with the dog, making it beg for scraps while the Uncle served a fry-up from the stove – eggs, bacon, black pudding – shuffling from the table to the stove in carpet slippers. The sound of them all eating. The Uncle asked was she enjoying her holiday and she said that she was.

__________________________________

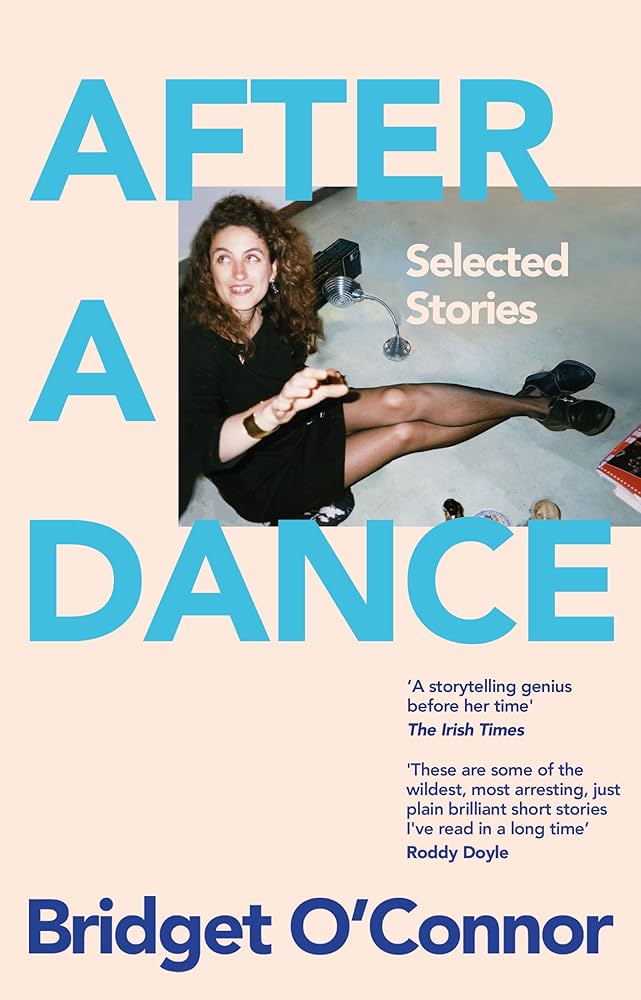

After A Dance: Selected Stories by Bridget O’Connor is published by Picador.