Adam Mansbach on the Difficulty of Writing an Honest Elegy About His Brother

Shawn Setaro in Conversation with the Author of I Had a Brother Once

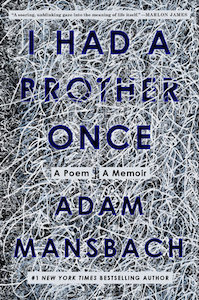

I Had a Brother Once is unlike anything Adam Mansbach has ever written. And that’s saying a lot. Mansbach may be best known for his “children’s book for adults” Go the Fuck to Sleep, but his career has spanned nearly every type of writing: literary fiction, screenplays, thrillers, middle-grade books, humorous takes on Jewish life and ritual, political PSAs, and more.

Now, there’s something different from anything else in his wide-ranging career. I Had a Brother Once bills itself as “a poem, a memoir,” and that’s exactly what it is. Adam’s younger brother David committed suicide almost a decade ago. Adam spent much of the intervening time writing about everything but his brother’s death, all the while planning to grapple with it at some point. He finally found the perfect form in poetry, something he hadn’t done professionally—and had hardly done at all—since his 2002 collection of poems Genius B-Boy Cynics Getting Weeded in the Garden of Delights.

I Had a Brother Once is a deeply moving and beautifully written take on suicide, trauma, memory, and who, in the end, gets to control a person’s story. I talked to Adam via Zoom on April 16, 2021—just two days in advance of his brother’s birthday. That’s where we began the conversation.

*

Shawn Setaro: As we’re talking, it’s two days before David would have turned 42. How are you doing?

Adam Mansbach: For the most part, I’m doing well. It’s really rewarding to have the book out in the world. It’s been a long time coming in the sense not just that it took me so long after his death to write the book, but also that because of the machinations of publishing and the world, it’s taken a long time for the book to come out. It got pushed back because of the election. It got pushed back because of the pandemic. So it just feels really good for it to finally be out in the world. I find myself feeling very, very supported.

I’ve never published a book this personal. I’ve always had the guise of fiction to hide behind. But it’s also been a long time since I’ve published a book that was a serious literary work. I’ve published a bunch of humor and a bunch of middle-grade stuff and screenplays and so forth. But it’s been a long time since I’ve been in the position I am now in. The landscape is very different. But I feel really supported by my friends and the community of writers that I’m a part of, and the feedback I’m getting from readers. There are remarkable levels of support for me on this book—not that that translates into sales or anything, but it feels good.

It feels good to be in that type of a place, and it feels like a weird kind of coming full circle. When my brother died, I was in the midst of the media flurry of Go the Fuck to Sleep. I was very deliberately and anxiously not talking about any of that stuff and fearing that I might somehow be asked to. It was this public performance of joy, balanced with this private grief and shock. So in a way, it feels full circle and a certain kind of resolution to now be out here deliberately talking about this and inviting those conversations and daring to hope that they might be of use to other people.

SS: Speaking of talking about your work, you’re the first person who ever hipped me on how to handle interviews. You told me that you shouldn’t be afraid of repeating yourself because it’s a different audience every time, and you shouldn’t use your best material only once. But this book is different than anything else you’ve written. How are you handling interviews for this book? Is your normal bag of tricks working?

AM: You know, it’s interesting. So far, given that we’re in this pandemic still and I’m not in bookstores and I’m not at events spaces, a big part of the strategy has been, get on Instagram Live and have conversations with folks. So I’ve been hitting up people close to me. There’s some comfort built into that. And then a lot of the other people I’m talking to who aren’t friends are grief professionals. I feel like I’m being interviewed by people who either know me well or know the terrain well, so that’s been nice.

There is always some degree of falling back on talking points as you figure out what those points are. I’m not one to come up with talking points ahead of time. I’m one to figure out what they are in the process of doing the interviews, and then refine and repeat them as the process continues. So there’s a bit of that. But also, I feel like I’m ranging pretty far and wide in my answers and in the questions I’m being asked, and there’s a lot to draw on in the book.

So it’s a mix. I feel like every time I have a conversation, I say some new shit, and I also figure out how to better say something that I’ve been trying to say. I think that’s in keeping with the book because a lot of what I’m dealing with in the book is my own relationship to narrative—which is a very solipsistic thing to say about a book that’s actually about grief and death and my brother and stuff that’s much more emotional than a heady idea like my relationship to narrative. But I guess what I mean is, there’s a tension between me wanting to be able to tell his story; and me not wanting to claim the authority to know what that story really is, wanting to keep alive the different versions of the story and embrace the various paradoxes of his life that without trying to resolve them or understand them.

SS: That reminds me of a moment in the book early on. You start telling the story, and then right at the moment when you’re about to mention your brother’s suicide, you have a digression. How did you get words on a page to evoke the feeling of procrastination?

AM: I wrote that section pretty much exactly as it appears in the book. There’s no version of the book that ever existed where my father calls me and says, “David has taken his own life” without that lengthy pause or digression or in breath. It very much mirrors the fact that I was unable to write this book for like eight years. Not that I sat here trying to write it, but I sat here thinking about how to write about my brother. I was pretty hard on myself. I kept very busy, I wrote a lot of things. But in the back of my mind, every project I was working on felt partly like an avoidance of this thing that I knew I had to write. I started talking to friends about it, but I never made any real progress.

So even when I did finally break ground on this project and start writing it, I had to start from a ways off and I had to digress at the critical moment before that knowledge hits and the whole world changes and the book changes. I had to do a lengthy lead-in. I had to come out before I could go in. It very much mirrors my relationship to trying to talk about this, trying to write about this.

SS: Definitely. So in that eight-year period, you wrote screenplays and thrillers and all kinds of stuff. When you look back at that material, do you see any grappling with your brother’s death that maybe you didn’t see at the time? Does it show up in Barry [Adam’s screenplay about a young Barack Obama, turned into a Vikram Gandhi-directed 2016 film] in some weird way or something like that?

AM: Barry might be one of the only places that I could see it showing up, because so much of Barry is about a kind of existential, unspoken discomfort and grappling. It’s about figuring out masculinity and feeling like an outsider and not necessarily having the language to articulate all of the shit swirling through you. I think in that text, yes.

I also don’t think the book could exist without some fundamental accounting of who he was and who I knew him to be.SS: The book is an elegy. But it’s honest in ways that elegies often aren’t. I was curious how you felt about making some of the less-than-flattering stuff about David public. I’m thinking in particular of when you say that a large part of his personality was kind of cobbled together from traits from other people.

AM: If there is a part of the book I was most hesitant or leery about, it certainly would be that section. Because it’s unflattering and because I know that my parents don’t probably agree with that in large part.

It’s exposing of him in a way. But it’s an exposing of him that’s entirely impressionistic and based on my opinions rather than a set of facts. You know, it’s one thing in my mind to relate the method of his death or the facts of his life. It’s another thing to do what I do in that section, which is give you my opinion. So yeah, I was a little leery of that, but I also don’t think the book could exist without some fundamental accounting of who he was and who I knew him to be.

He would be a cipher and the book would be a cipher if I didn’t at some point really try to talk about him—not just his death or not just who he was as a concept, as a person who was here and then wasn’t, or someone who only exists relationally to me or my parents or whatever. At some point, I did feel like I had to try to go in.

But it’s also tricky also because suicide does have the effect on me of rewriting a lot of the narrative and making you go back and reconsider a lot of things. So I talk in the book about when my cousin and I went to his house to gather things up for his wife. I was looking at photographs I’d seen before many, many times. They look different now.

Photographs in my parents’ house, even the last photograph of him and me together at our grandfather’s memorial. Every time I looked at these photos before he died, it seemed like he was looking at the camera. Now he doesn’t appear to be looking at the camera anymore. His gaze looks sunken and distant, like he’s not really there. All of these things take on different meanings, darker meanings. So I’m left with the question of how much of my accounting of him as a person and describing his personality is fundamentally shifted by his absence.

All the things I say are things I knew about him on some level before he died, but I put them together differently. The absence, the cobbling together of a personality, the adopting of traits from other people—it just takes on a different air. I probably recognized 15 years ago, huh, Dave talks to dogs exactly the way our mother talks to dogs. Dave, when he orders a drink, always just orders the drink that our cousin Matthew orders. But it comes together very differently after he’s gone. So if there was a part that I was uneasy about my parents reading, it was that part, for sure.

SS: How has your family reacted to the book?

AM: They’ve been extremely supportive. I wrote my parents this email where I explained that I had always known that I would write about David, that I hadn’t been able to figure out how, but that it was inevitably going to be part of my grieving process, and that already my life felt different after having written it. They both wrote me back immediately saying, “We get it. We’re so happy to hear it.”

I didn’t actually show them the book until it was in its almost finished form. And they were both super supportive, said that the book was beautiful, said that they appreciated it. My father went further. His fears in thinking about what I would eventually write were that I would get some shit wrong or say some shit that he didn’t agree with. I’d have a different version of events or of David than his, and that would cause him pain or make him uneasy. Specifically around the question of whether my brother might have had Asperger’s, which I spent maybe two lines on.

It’s irrelevant ultimately whether he had it or not. To me, some of the things about him line up with it. I know that my parents absolutely disagree with that. But my father said, “I’ve come to a point where I understand that your version is valid and your version doesn’t have to be definitive and doesn’t have to cause me stress or pain. I can just accept it as your version and the truth from you and for you.” I thought that was above and beyond. I mean, there’s support and understanding, and then there’s that.

__________________________________

I Had a Brother Once is available from One World, an imprint of Random House, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. Copyright © 2021 by Giants of Science, Inc.