Accounting for the Unaccountable: Daniel Johnson on Writing about His Friend, James Foley

On Memorializing a Meteoric Life After an Unimaginable Loss

August 19, 2014: Panicked, I locked myself in the first-floor bathroom of our 1905 Colonial in Boston. I didn’t want my kids to see their father melt down. I pressed my hands into my eye sockets. Sobs cut loose from my chest. I ran water over my face, then picked up my cell phone.

I left a voice message for Ricky. When Savage picked up, I told him, “I have terrible news about Jim…he’s been killed by ISIS, beheaded. There’s a video; don’t watch it.” I called Durkin. Then, I called a dozen other friends. There’s humanity, I’ve learned, in relaying bad news personally.

When I entered the living room, I could hear Ebele talking to Luka and Olanna, ages 2 and 4.

“What happened to Uncle Jimmy?” Olanna was asking. Ebele, sitting on the floor beside them, with wooden train tracks all around, responded, “Uncle Jimmy got hurt. He got hurt really badly.”

*

My closest friend for nearly twenty years, James Foley and I met in Teach for America in 1996. We shipped out to Phoenix, where Jim taught middle school history. I taught 5th and 6th grade bilingual students. Despite our teacher bootcamp, things quickly took a turn for the worse in our classrooms. Jim’s students formed the “We Hate Mr. Foley Club.” In classroom 33, Francisco unleashed a series of cartwheels, as I tried to teach geography. Nights and weekends, Jim and I took refuge in our newfound friendship. When we should have been hatching lesson plans, we swapped poems and stories. Together, we made a pact to become writers.

Together, Jim and I shared some of our life’s greatest adventures. We sky dived with friends over the Sonoran Desert. We sneaked into Cuba together when it was illegal to do so. Following Bush’s re-election, we got arrested protesting the 2004 Republican National Convention in New York City. Jim stood up in my wedding. In fact, Jim’s the reason I met my wife Ebele in a blizzard on New Year’s Eve on Manhattan’s Upper West Side.

As bibliophiles, Jim and I always talked books, and exchanged them as gifts around the holidays. Days after Jim’s execution, I was sitting, dazed, in my sun-baked study on an August morning. When I opened my copy of The Unabridged Journals of Sylvia Plath, I found this feral, loving inscription scrawled on the title page, “DJ—fuck it believe—Jimmy ’06.”

*

A freelance conflict reporter, James Foley was reporting from Syria during the Arab Spring, when he was taken captive on Thanksgiving Day 2012 along with English reporter John Cantlie. Jim went missing for nearly two years. Eventually, he ended up in the hands of ISIS, a growing presence in Syria at the time, as they rallied to establish a caliphate. Feeling powerless and terrified during his captivity, I wrote to Jim directly from my third-floor study, since writing is the closest thing I know to prayer.

On August 19th, Jim’s ISIS captors shot a video outside of Raqqa, Syria. The video—it’s still hard for me to write these words—shows Jim kneeling in an orange jumpsuit next to his black-clad captor, who is holding a hunting knife. Jim reads a statement composed by ISIS, pleading for the United States to leave the Middle East and more. I’ve never watched the video beyond this point, but it cuts to an image of him, headless. Millions of viewers around the world watched the video. And Jim’s body was never recovered.

According to a news report at the time, the image of James Foley on his knees in the desert became one of the most recognizable images to Americans of a certain age, second only to the photo of planes colliding with the Twin Towers. Even nine years after his death, the image of James Foley kneeling in a Guantanamo-orange prison jumpsuit dances across our collective conscience still.

*

Planes hitting the twin towers. The image of Daniel Pearl, hands shackled in his Pakistani prison cell. The Alfred Murrah Federal Building in Oklahoma City toppling. A Boston Marathon runner swept from his feet by the force of a pressure cooker bomb.

The incessant replaying of certain images or videos by the media, in a certain way, mimics the behavior of traumatic memory. According to neuroscientists, the brain consolidates or processes such memories differently. Due to the firing of stress hormones, traumatic memories become unstable in a sense. As a result, they can flicker and dance before our eyes, unsummoned, say, during a candle lit Christmas dinner or on a blustery drive on I-95 from Boston to New York.

After Jim’s death, we imposed a news blackout in our home. Still, I saw the image of Jim on his knees play in the airport, repeated on a row of televisions being sold by an electronics store. I couldn’t get away from it, just as Jim’s fellow American and British hostages couldn’t escape their bondage. Following Jim’s death, ISIS beheaded a string of captives over a series of days and weeks: Steven Sotloff, David Haines, Alan Henning, and Peter Kassig. The tremors of these executions rocked me for weeks and months after. On the other hand, remembrances by friends, family, and fellow journalists offered a certain balm and solace. An ABC News report shared that Jim had videotaped the midnight wedding of Abu Khaled, a Syrian sniper, to his fiancée, a young nurse who treated his leg wound. A recollection by filmmaker Brian Oakes in Jim: the James Foley Story details how Jim raised money for the citizens of Aleppo to purchase their own ambulance to ferry their wounded to safety.

*

After James Foley’s death, I moved through my days in a stunned, leaden fog. I broke down weeping at work. I cried on my bicycle while pedaling to the Writers Room. Over and again, I saw things that weren’t there. On an airplane TV, I clearly saw a field of headstones. Seconds later, I realized it was a crowd of people watching golf on a hillside. I saw a square-jawed journeyman with F-O-L-E-Y lettered on the back of his EverSource jacket. As he disappeared into a manhole on Hyde Park Avenue, I stopped my car and nearly flung open the door, my kids asking what it is was. “It’s just that I thought I saw…”

*

Grief is a behemoth, two-story granite boulder parked in your living room. Glacially cold, immovable. Impossible to step around. Occluding sunlight. Dripping water on your rug.

Deranging how you move through the world. Dirty, unyielding.

*

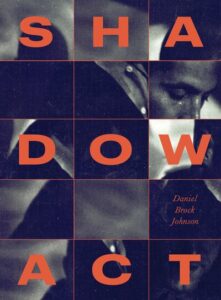

From Joan Didion’s The Year of Magical Thinking to Paul Monette’s Love Alone to Hisham Matar’s The Return and Tahar Ben Jelloun’s This Blinding Absence of Light, contemporary literature is rife with novels, memoirs, stories, and essays that traffic in trauma, grief, and memory. I took refuge in all of these books, but Edward Hirsch’s Gabriel proved to be a touchstone text for me while I was writing Shadow Act: an Elegy for Journalist James Foley. A dizzying book-length elegy, Gabriel chronicles the disappearance of the poet’s son Gabriel during Hurricane Sandy in New York City.

The reader falls through untitled strophes, each written in tercets that pulse with the father’s attempt to map the ache, confusion, pain, and obsession of losing, finding, and losing, again, his adult son. Hirsch humanizes Gabriel by detailing his quirky ticks, cataloguing the schools Gabriel left during his complicated childhood, and sharing second-hand recounting of stories from Gabriel’s’ friends. “Many of us carry the dead around with us,” Hirsch has said of writing Gabriel. “We shouldn’t feel ashamed of that.”

*

As I hunkered down at the Writers Room of Boston to write about Jim’s life and death, I drafted dozens and dozens of poems in a variety of forms and styles. Grief-stunned, I did so out of a ravening need to continue speaking to Jim. During this time, I recall listening to a radio segment on This American Life titled “One Last Thing Before I Go.” In it, a reporter plays clips of tsunami survivors talking to their lost loved ones over a “wind phone.” A disconnected rotary phone placed in an English style phone booth, the wind phone allows for grief pilgrims to speak directly to the dead, to let their voices ride on the winds and water. In one clip, a teen girl speaks searchingly into the wind phone, “Dad? Mom? Nine? Isse? It’s already been five years since the disaster. If this voice reaches you, please listen…” As I wrote to and about Jim, day after day, I realized that writing poetry had become my own kind of wind phone.

In January 2016, a year-and-a-half after Jim’s murder, I showed up at the Cambridge Boathouse with a sheaf of poems. Wind whistled across the frozen Charles River and through the boat house windows. When I took the mic to share my work-in-progress with other alumni of the Warren Wilson Writing program, my throat constricted. My chest tightened. My mind seized. I could barely choke out the words. This wasn’t ordinary stage fright. It was something deeper, much rawer. My body and mind were reacting as if I’d just viewed the video of Jim’s execution, again. I had no temporal distance, no real emotional remove. “Does anyone have a bottle of whiskey?” I asked, attempting to make light of the situation. I could see my own shock and panic mirrored back in other peoples’ eyes. I struggled through several more poems and took my seat. A friend checked in with me after, offered a hug and some words of comfort.

While reading How to Tell a Story, a collection compiled by the storytelling nonprofit The Moth, I encountered a section titled “Are You Ready to Tell Your Story?” The collection’s writers note that they often, half-jokingly, urge their storytellers to wait “ten years after a death and five years after a divorce,” before treating certain subjects. A Lutheran minister coaches that it’s important to “preach from her scars and not her wounds.” At the Cambridge Boat House reading, it’s clear I was reading from my wounds, not my scars. How to Tell a Story is packed full of practical advice, such as how to recognize signs that you might not yet be ready to share your story: you keep blowing deadlines, you have trouble organizing the subject matter, you experience physical symptoms that go beyond normal stage fright. The same chapter describes how writing about traumatic memory can allows our brains to make new connections to that memory by assigning feelings and sensory impressions experienced at the time, eventually quieting the mind. In short, writing about trauma can help us overcome trauma.

*

Shadow Act: an Elegy for Journalist James Foley has taken me more than 12 years to finish. Part of my challenge has been artistic—how to structure a collection in poetry and prose to mirror the labyrinthian mazes of grief, reflect the obsessive accounting for the unaccountable. Looking back over manuscript drafts, I can see that I spent five years on the structure alone. During this time, I layered prose and poetry, collaged footnotes, elegies, erasures, and more to create a hybrid, memoir-in-verse that moves back and forth in time, mirroring the horrors of Jim’s capture and disappearance in Libya and his second abduction in Aleppo, Syria on Thanksgiving day. In the final collection, fragments of a lyric essay, as one friend put it, float up like “pieces of a shipwreck.”

I wrestled with wrenching doubt and uncertainty. Would publishing Shadow Act would mark the end of my conversation with Jim? What if it signaled a second and perhaps even deeper loss?The larger challenge of finishing Shadow Act has been this—how can I prepare myself emotionally to share these poems? I’ve worked with a therapist. I’ve raced in the Foley 5K and supported the James Foley Legacy Foundation, a hostage advocacy nonprofit founded in the wake of Jim’s death. Each fall, I’ve gathered with a dozen of Jim’s closest friends, most recently on the banks of Lake Winnipesaukee, where Jim grew up, to tell stories, share drinks and laughs, and build community, while mending our broken parts. When I was certain I was done with my book, I even shared my final manuscript with Jim’s parents to ask for their blessing.

Still, I wrestled with wrenching doubt and uncertainty. Would publishing Shadow Act would mark the end of my conversation with Jim? What if it signaled a second and perhaps even deeper loss? Another fear, among countless others: what if I wasn’t able to read poems like “Shadow Act,” without breaking down? The book’s title poem paints a loving portrait of my wife shaving my head during COVID lockdown, then jump cuts to Jim’s ISIS captors shaving his head before his execution.

After our wedding in New York City in 2006, Jim would often visit our home on Poplar Street in Roslindale, on New Year’s, during breaks in reporting from Iraq, Libya, and Afghanistan. I remember Jim freeing Olanna, age 10 months, from her highchair and whirly-birding her around the kitchen. More than once during these visits, Jim encouraged my wife, Ebele, and me to perform together, since I’m a writer, and she’s a classically trained soprano.

On June 15, 2023, my wife Ebele and I took the literary stage at GrubStreet’s Center for Creative Writing in Boston’s Seaport for a pre-release celebration of Shadow Act at Porter Square Books. Dozens of friends came out to show their support. Jim’s parents sat in the audience next to both of his brothers. With my wife at my side, I felt strangely calm, warmed by the love in the room. A far cry from the panic and terror that flooded my nervous system seven years earlier at the Cambridge Boathouse.

As Ebele and I offered up our multimedia tribute in poetry, video, and song to James Foley, our gentle, complicated friend, I felt a sense of awe, grief, love and anguish, all at once. But, most importantly, I felt control over these emotions. At long last, I felt in control of my story. Perhaps this marked the beginning of a healthy-but-not-final letting go—a move to share our friendship with others, a chance to overwrite Jim’s horrific death by celebrating his meteoric life as an educator and journalist, as a friend who wandered and was lost.

____________________________________________

Shadow Act: An Elegy for Journalist James Foley by Daniel Brock Johnson is available now via McSweeney’s.