Aaron Hamburger on Trying to Solve a Family Mystery Through Fiction

“Writing my novel was a way to connect to this younger version of my grandmother.”

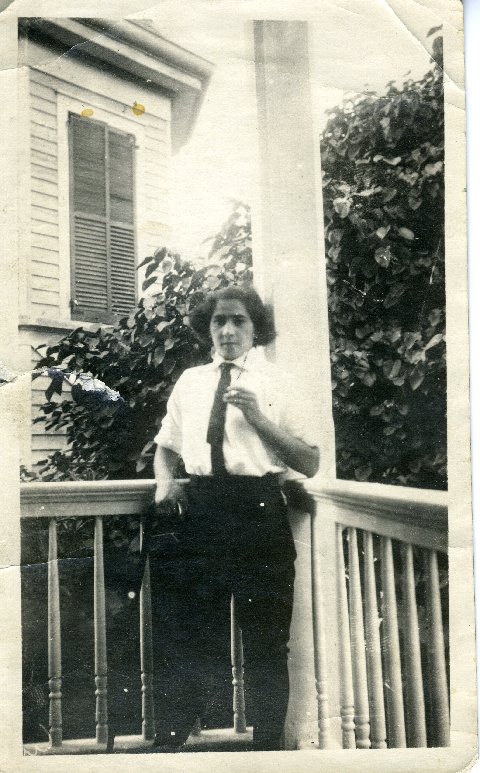

Six years ago, I found this mysterious picture from 1922 of my grandmother dressed in full male drag.

As a kid growing up in Detroit’s suburbs, I knew my grandmother as a frail old woman in tweed skirts who fed me Hershey’s kisses and rocked me in her lap singing lullabies in her thick Yiddish accent.

What a far cry from the young woman in this startling photo, dressed in a man’s shirt, tie, and pants, staring at the camera with a mysterious, haunting expression, a mix of daring and fear, frankness and unease.

As a gay man with no LGBTQ relatives in my immediate family, I was enthralled. For weeks, I shared this image with friends, colleagues, students, even a United States Senator whom I visited to lobby for immigrant rights. I remember showing it to my friend, the writer Leslea Newman (author of Heather Has Two Mommies), who said aloud what perhaps many of us thought, “Your grandmother looks like a butch lesbian! I have a total crush on her!”

Looking at her picture now, I wish I could speak to her.

I had to know the circumstances behind the photo. Why was my grandmother dressed this way? Who was she as a young woman? What was her story? In trying to answer those questions, I wrote a novel, Hotel Cuba, inspired by the incredible facts I discovered.

I began by listening to hours of recorded interviews that my brothers conducted with my grandparents about their immigration stories, back in 1976. For a precious fifteen minutes of these recordings—first done on cassette, then digitized—my grandmother described in broad outlines how she fled the Russian Revolution to get to America, stopping unexpectedly in Havana, Cuba, where she lived for a year, and then Key West, where the picture was taken.

I then spent years researching to fill in details my grandmother left out. I interviewed other family members as well as writers, historians, and scholars who’d studied the lives of similar immigrants. I read primary and secondary sources, and traveled to Havana and Key West, where in 2018 I tracked down the exact location of the photo.

Here is what I found.

My grandmother was one of eleven siblings who grew up in a rural Russian shtetl in today’s Belarus, near the Ukrainian border. The family originally hailed from the big city of Vilnius in Lithuania, giving them a sophisticated cosmopolitan status. And as the daughter of the town cantor (who was also the town’s kosher butcher), my grandmother was relatively well-off.

Then came World War I, the Russian Revolution, and a war between Poland and the new Soviet government. From week to week, my grandmother’s town was invaded by Reds, Whites, Germans, Poles, or armed bandits, who pillaged, raped, and murdered at random.

Somehow my grandmother’s family scraped together the money to send her and her sister to America. The two young women made an arduous journey across a war-ravaged wasteland to Warsaw, where they learned that the U.S. had recently changed its immigration policy as a result of the new Emergency Control Act of 1921. Like the more recent “Muslim Ban” put forward by former President Trump, the law limited immigration from a geographic area (Eastern Europe) where the immigrants were predominantly an ethnic group (Jews), who were the object of fear and suspicion in America.

Then my grandmother heard about a loophole in this new law: Would-be Eastern European immigrants could go to Cuba, establish residency after a year, and enter the U.S. legally, avoiding the new stringent quotas. During my research, I learned that the steamship companies, which had been doing big business ferrying immigrants to the U.S., actively promoted destinations like Cuba, Mexico, and Argentina as alternatives to Ellis Island.

“So we went,” my grandmother says in her recording. Three simple words to capture the torturous three-week voyage across the rough North Atlantic Ocean in 1922, crowded in the dark belly of a ship where passengers crowded together, sweating, pissing, puking, farting, screaming, crying, and having sex.

Picture my grandmother and her sister arriving in Havana, two young women from a landlocked isolated Russian village buried in snow and ice each winter, now walking down a blazing hot gangplank, dressed in their best and heavy woolen European clothes, sweating in the intense heat of a tropical Caribbean island. They knew no one, didn’t speak the language, didn’t recognize the food, the architecture, the plants, or the trees. Moreover, Cuba was going through an economic depression due to plummeting sugar prices after World War I.

My grandmother recalls being helped by a Jewish aid society, likely a group formed by American Jews living in Havana called the “Ezra Society,” an offshoot of the American group HIAS (Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society). Volunteers met single women like my grandmother at the docks and found them homes and work. My grandmother, a skilled seamstress, and her sister were housed with a middle-aged childless Jewish couple who owned a business making hats. There were many such small workshops run by Jews in Old Town Havana.

I felt I was finally getting to know my grandmother not as a “bubbie,” but as a woman.

My grandmother’s sister was impatient to join her boyfriend from Russia, now settled in the United States. So she paid an American tourist couple to pretend that she was their daughter and take her back with them. This was during Prohibition, when alcohol tourism in Havana was so rampant that a popular song in America, “I’ll See You in C-U-B-A” by Irving Berlin, was devoted to this theme. Also important to note, passports were a new invention and not rigorously checked. They consisted of single sheets of paper with blanks that were filled in with a pen and typically issued to male heads of families, i.e. “Joe Blow, his wife Jane, and daughter Jennifer.” It would have been easy to write in an additional female family member.

After her sister got into the U.S. this way, my grandmother followed suit. She paid an American couple all her money, ten dollars, to accompany them on the ferry from Havana to Key West as their daughter. However, immediately upon disembarking in Key West, she was arrested and detained while her case was investigated, to see if she was involved in human trafficking. After two weeks, she was deported back to Havana without a cent to her name.

Tom Hambright, a historian of Key West, told me it was likely one of the ship’s staff had informed on my grandmother because the shipping companies were held liable for undocumented passengers. He also believed that my grandmother would have been remanded to the custody of the Jewish community of Key West rather than incarcerated because the judicial system didn’t understand how to provide Jewish detainees with kosher food.

In fact, while talking about Key West, my grandmother mentions a man named Rabbi Shulsinger. She says she told this rabbi that her father was also a “shul-singer,” a cantor, hoping this rabbi would treat her better. Arlo Haskell, author of The Jews of Key West, confirmed to me that the chief rabbi of Key West was named Rabbi Lazarus Shulsinger. When I visited Key West, Haskell showed me the building that housed the city’s synagogue as well as the living quarters of the rabbi. Today it’s a Sarabeth’s restaurant.

Everywhere I walked in Key West, I compared my copy of the iconic photo to each balcony I passed. Finally, on my last day in town, I figured out what I was looking for had been right under my nose. Studying the second floor of the living quarters attached to the old synagogue, I realized it was a former balcony that had been filled in and converted to an interior room. The roofline of the neighboring building was an exact match to the one in the background of my grandmother’s picture.

I’d found the where and when of the photo, but maddeningly, I never determined why my grandmother was dressed in men’s clothes. Perhaps she had no spare clothing, and this was what Rabbi Shulsinger gave her to wear. My research into period fashion indicated that androgyny was in vogue, though women generally wore flowing pants, like bell bottoms, that swelled around the calves. Another possibility: Undocumented immigrant women used to get into the U.S. by cross-dressing as male sailors.

Ultimately, though, writing my grandmother’s life story taught me something else, perhaps more important. I felt I was finally getting to know my grandmother not as a “bubbie,” but as a woman. In animating her story, I imagined the heady thrill she might have felt putting on a man’s outfit, maybe a sense of unfamiliar power. Perhaps she felt nervous about the traditional Jewish ban on cross-dressing. As a seamstress, she would have found clothes important, a way of telling stories, of creating a self.

Looking at her picture now, I wish I could speak to her, first to reassure her that she would make it to America and live a rich, full life. Then I’d like to ask questions, so many questions! In her twenties, my grandmother had been curious about the world, still figuring out who she was, just as I had been in my twenties. Writing my novel was a way to connect to this younger version of my grandmother and imagine how her remarkable journey transformed her into the person I once and all too briefly knew.

__________________________________

Hotel Cuba by Aaron Hamburger is available from Harper Perennial, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.

Aaron Hamburger

Aaron Hamburger is the author of the story collection The View from Stalin’s Head—which won the American Academy of Arts and Letters’ Rome Prize and was nominated for a Violet Quill Award—and two novels, Faith for Beginners, which was nominated for a Lambda Literary Award, and Nirvana Is Here, winner of a Bronze Medal from the Foreword Reviews Indies Book Awards. His writing has appeared in the New York Times; Washington Post; O, The Oprah Magazine; Tablet; The Forward; and numerous other publications. He lives in Washington, DC.