“In short, all a young poet needs in order to survive a broken heart is: (1) one button-down shirt or dress, scintillating; (2) one sheet of tissue, premium; (3) a pair of running shoes, soles intact; (4) one novel by a writer with an intimidatingly long name; (5) one empty cardboard instant-noodle box; (6) the album Blue by Joni Mitchell; (7) and one book unburdened by whether “where” in Indonesian should be “dimana” or “di mana” because it’s written in a foreign language, say, Finnish.”

Article continues after advertisement–Ginanjar Dantonik, romance consultant

on the now-defunct Rawa Belong Young Poets’ Community listserv

*

Two weeks after it happens, slip on a bright-colored T-shirt, exchange your thick glasses for contact lenses, and when people ask how you’re doing, reply, “I have to admit it was pretty tough at first, but things have started to really improve these past few days.” Don’t say that you weren’t crushed in the least because you saw it coming from the start—no one will buy it. Head to the library first thing Monday morning. Not on the weekend. They’ll think you have no life. Return your favorite books of confessional poetry; you won’t need them anymore. Borrow history books—on Dutch colonization, on world history for kids. And when the librarian asks, tell them you’re writing a novel that takes place over a period of three hundred years. Tell them one of your characters is an accountant who experiences the stock market crash of 1929. Tell them that you yourself are a work in progress, ever progressing, ever progressing.

If a friend invites you over for dinner, don’t turn them down like you’ve done before. Even though it’s your first chance to, don’t bring a date—you’ll look like you’re trying too hard. Bring a bag of mangoes; wear a little red dress. When people ask you for a timeline of the events that led to your breakup, keep it short. Some popular responses, by way of example: “We both liked to read, but turns out you need a better reason to stay together.” Or, “It made sense, I guess—he found a better option.” Or, “His farting problem was unbearable.” Don’t bother to lie about your supposed novel project if they don’t ask. They won’t really care.

When someone invites you to dinner a second time, you’re allowed to turn it down. Just say you’ll be visiting your parents in Rawa Belong that weekend. When you get invited a third time, accept. If anyone asks you what you’re reading, just laugh. If they push, say that you’re reading Ziggy Zezsyazeoviennazabrizkie’s latest novel in between working on your own book—chances are, they won’t ask further questions. If anyone offers to set you up on a blind date, nod— most of the time such offers are empty talk anyway.

Go jogging every morning. You need the endorphins and also quiet moments for yourself. Don’t bring your iPod. And don’t catch Pokémon. Turn all your focus inward. If you see any of your college classmates, say hi. If they invite you to run with them, say you’re happy with your current route. If they say, all right, they’ll join you, reply, “Perfect!” and laugh. Don’t sing to yourself while you’re running—they’ll think silence makes you uncomfortable. Respond to any remarks they make, whether political, pseudoaltruistic, narcissistic, or even poetic.

On Thursday afternoon, go to campus, to Building E—where they hold a weekly discussion seminar on politics. The day before, search for essays written by that week’s speaker. Digest them. Reread them. Visit the websites for various arts and political magazines and read all the free articles. Subscribe to their newsletters. Block the ads. Use a VPN. Bring a plastic pencil case with you every Thursday. During the seminar, sit in the front row. Ask insightful questions during the Q&A. Avoid “Uh, not a question so much as a comment . . .”—it’s boring and not the right place for it. When the event is over and everyone applauds, drop your pencil case. Capitalize on it and linger for a while. When the speaker says hello and starts talking to you, indulge him. Say that you found the radical ideas in his essays fascinating. Mention one of the titles, then say it’s your favorite. If he responds indifferently, say good night and go. If he asks for your number, give it to him. If he asks you out for coffee right then and there, say you’ve told your friend you’d accompany him speed dating, then add casually, “But if you ever wanna hang out, just call!” Of course, he’ll say of course. Then head back to your rented room.

The weekend will come when you feel the temptation to crack open your Schopenhauer and your volumes of poetry by Sexton and Plath. Resist. Instead, try contacting your friends to see if they’re up for dinner. Not at your place, because your room looks like a Pollock painting. Ask if they want to try that Thai restaurant in Plaza Senayan— the portions are big, enough for two to three people. At nine o’clock, go to bed. Get enough sleep to ensure optimal mental health. If you really can’t stand not reading philosophical works anymore, and your anxiety is keeping you up at night, then you may read Bertrand Russell’s The Conquest of Happiness. It’s a short book, and although it starts out a bit pessimistically (in essence: modern society makes happiness impossible), the rest of the book displays emotional and intellectual maturity.

One night, your ex will call you. Don’t overthink it. The most likely explanation is that his new boyfriend is working late and he’s bored. Keep in mind: His new boyfriend is much “prettier” than you, has Javanese aristocratic blood, and speaks with a fake British accent (if you were to chat with him, he’d casually mention he just got back from holidaying in Bora-Bora and keep saying “dove,” a.k.a. “dived.” “I dove,” he’d tell you. “Yeah, dah-ling. I dove.”) If your ex asks, say you’ve just returned from a discussion seminar on politics. He’s sure to fall silent. Dumping you didn’t motivate you to become more like the bare-chested men on his dating app. How sad. “Politics?” he’ll say in a tone of surprise. Laugh lightly and say, “Oh, it’s not like that. [At this point, laugh again.] I was just keeping a friend company.”

He’s bound to ask, “A friend? Who?”

Say, “From my writing class. You don’t know him.” He’ll be curious. But don’t keep going. Stop there.

One night, most likely when it’s pouring outside, he’ll call and say he’s broken up with his boyfriend. He’ll say his new ex was too preoccupied with his own ambitions—as if that were some sort of abomination. He’ll say his new ex spilled coffee all over his books and said, “Sorry dah-ling. My coifey velt.” He’ll say he never felt understood. He’ll say he was wrong. Now here he is, trapped in a taxi stuck in traffic in Semanggi, burning through all his phone credit and a significant number of calories, all for the sake of hearing your voice. He misses the sound of your laugh. “I kept calling earlier, but you didn’t pick up!” He’ll say he wants to come over, stay the night if he can. “Sometimes you just need someone to hold you, y’know?” Tell him, “I’m busy writing my novel. I’ll call you when I’m free.”

Attend the weekly politics seminar again. Become a regular attendee. One evening, you’ll get a text from Speaker Guy: “I’m in your neighborhood. Want to hang out?” Answer, “Sure.” Take a shower. Apply deodorant. On a scale of one to ten, your appearance has to rate at least a seven. If you arrive first, look for a table with dim lighting—suitable for hiding acne scars and wrinkles. Order only mineral water, as if to say, I didn’t want to start without you.

He’ll be glowing with happiness when he shows up. He’s been thinking about his conversations with you at the seminar. It’s no big deal—but they’ve intrigued him. He’ll ask if you’re seeing someone at the moment. Say, “Just broke up. Third party. My ex-boyfriend was really something else.” He’ll probably be taken aback by how calmly you speak about your sexual orientation. He’ll ask what you’re doing these days. “I’m writing a novel structured around parallel stories, à la Péter Nádas.” He’ll ask what happens in the first part. “An accountant in 1929, facing the Great Depression. A sort of how-to.” Later, when he gets a bit drunk, he’ll ask stupidly, “What is love?” Reply, “Dutch colonization.”

One night, your ex will pull a silly move. He’ll come over to retrieve some things he left at your place—items of sentimental value: (1) five pirated Monty Python’s Flying Circus DVDs, (2) a mountain of modern men’s lifestyle magazines, (3) it turns out there is no three, which becomes clear when he’s standing awkwardly in the doorway of your room. “Oh yeah . . . this is it, I guess.” Let him in, saying, “It’s all right. Don’t bother taking off your shoes.” Don’t help him search for anything. He’ll start, then ask what you’re doing these days. Gesture around yourself and reply, “As you find me, my dear Vodka. As you find me.” Say it with a weary, but-what-can-you-do air. He’ll ask for a box for his stuff. Go to the kitchen. Grant him, free of charge, one cardboard instant-noodle box— so you can say, “Like our relationship. Quickly consumed and cancer-causing.” He’ll say goodbye. Don’t see him out.

At your next gab session, Speaker Guy will lend you his favorite book. Start writing your novel. In return for the high-quality reading material, show him excerpts from your manuscript. Sometimes, late at night, send him memes or silly YouTube videos. Take him to the secondhand bookshop in the basement of Blok M. When the two of you are alone, play Blue by Joni Mitchell on repeat, all day, all week, all month. If he can stand it, then he’s the man for you.

When Speaker Guy opens up to you about his absent father, plan a pescatarian party. Invite all your closest friends. Check Speaker Guy’s tweets. Search for tweets about some amazing book he really wants to read. Order a Finnish edition. Buy crates of beer and fizzy drinks; soy-bacon; battered salmon skin, ready to fry; oven-roasted peanuts; vegetable frittatas; tuna sausages; all kinds of crisps: sweet potato, tapioca, potato, and banana. In the morning, the day before the party, take him jogging, just the two of you. He rarely exercises; he’ll be awed by your stamina. At the party, introduce him to your closest friends without elaborating, “He’s my blah-blah.” They’ll be dying of curiosity. Give him a glass of beer, maybe two. Then a glass of Fanta, maybe two. When he finally excuses himself to go to the bathroom, get out the Finnish book. Pick up his bag, which he’s left on a side table. Head to your room. Grab a pen and a tissue.

Place the book inside his bag. But before that, slip the tissue between the pages. And before that, on the tissue, write this poem:

He asked me to return everything in the rainy season

He asked me to return everything to the rainy season

To the rainy season I returned everything he’d ever asked

To the rainy season on the rainy season I asked for a rainy season

This whole time he’s given me a rainy season hue

This whole time he’s painted me a rainy season hue

Now he asks me to return the Rainy Season to him

And I return it in full

And I return in full

__________________________________

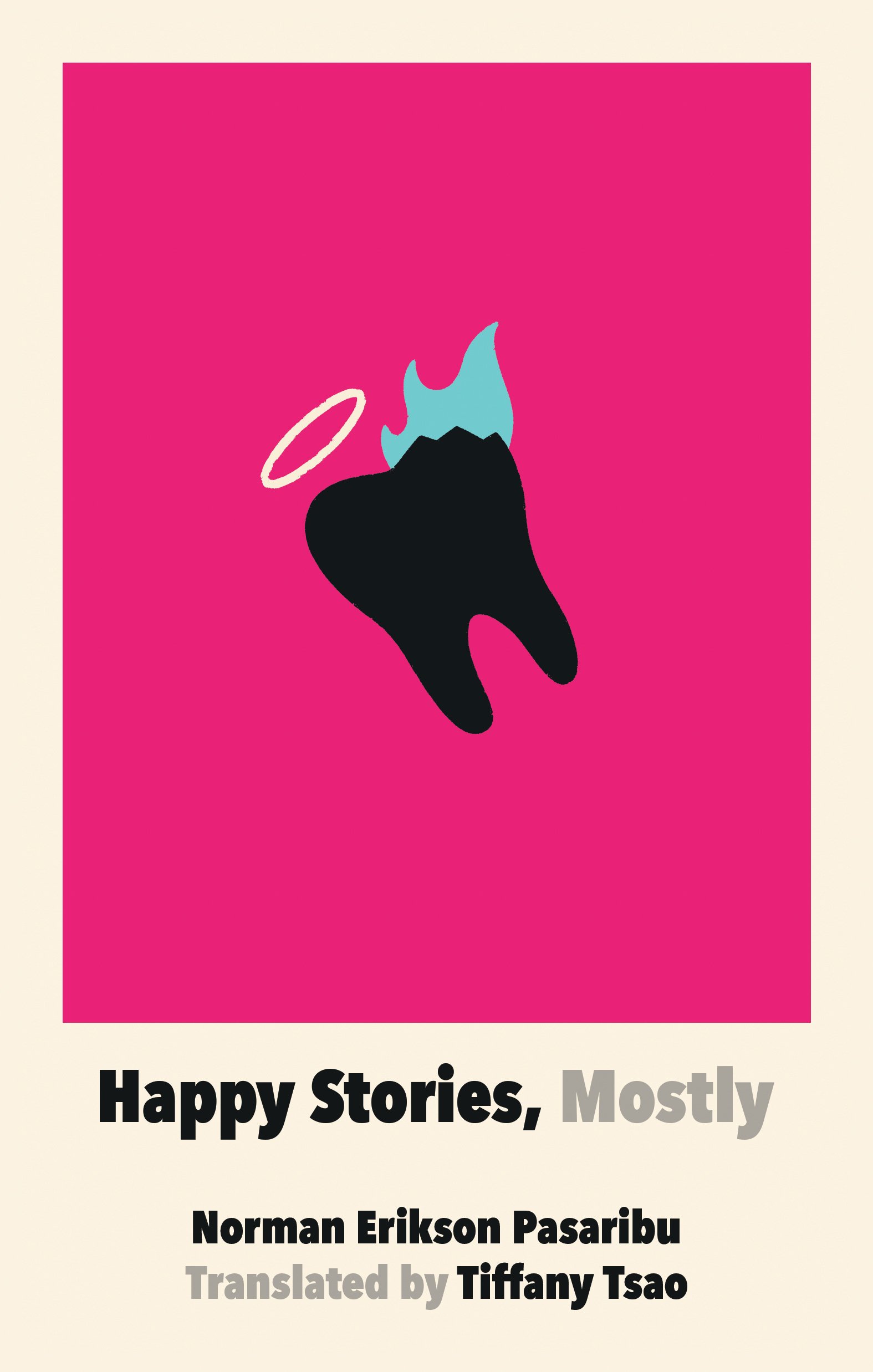

From Happy Stories, Mostly by Norman Erikson Pasaribu, translated by Tiffany Tsao. Used with permission of the publisher, Feminist Press. This story previously appeared as “A Heartbreak Survival Kit for Young Poets” translated by Shaffira Gayatri in The Near and the Far, Volume 2, edited by David Carlin and Francesca Rendle-Short, and published by Scribe in 2019.